The story goes that, after Rem Koolhaas had been appointed to design the McCormick Tribune Campus Center at the Illinois Institute of Technology in 2003, the legendary architect noticed how students had created their own pathways between the buildings on the site. The site of the new building included a field on which their footprints had worn down the grass to such an extent that distinct grooves had been carved out that reflected their movements, prompting him to consider the effect of desire lines on organic design.

The story goes that, after Rem Koolhaas had been appointed to design the McCormick Tribune Campus Center at the Illinois Institute of Technology in 2003, the legendary architect noticed how students had created their own pathways between the buildings on the site. The site of the new building included a field on which their footprints had worn down the grass to such an extent that distinct grooves had been carved out that reflected their movements, prompting him to consider the effect of desire lines on organic design.

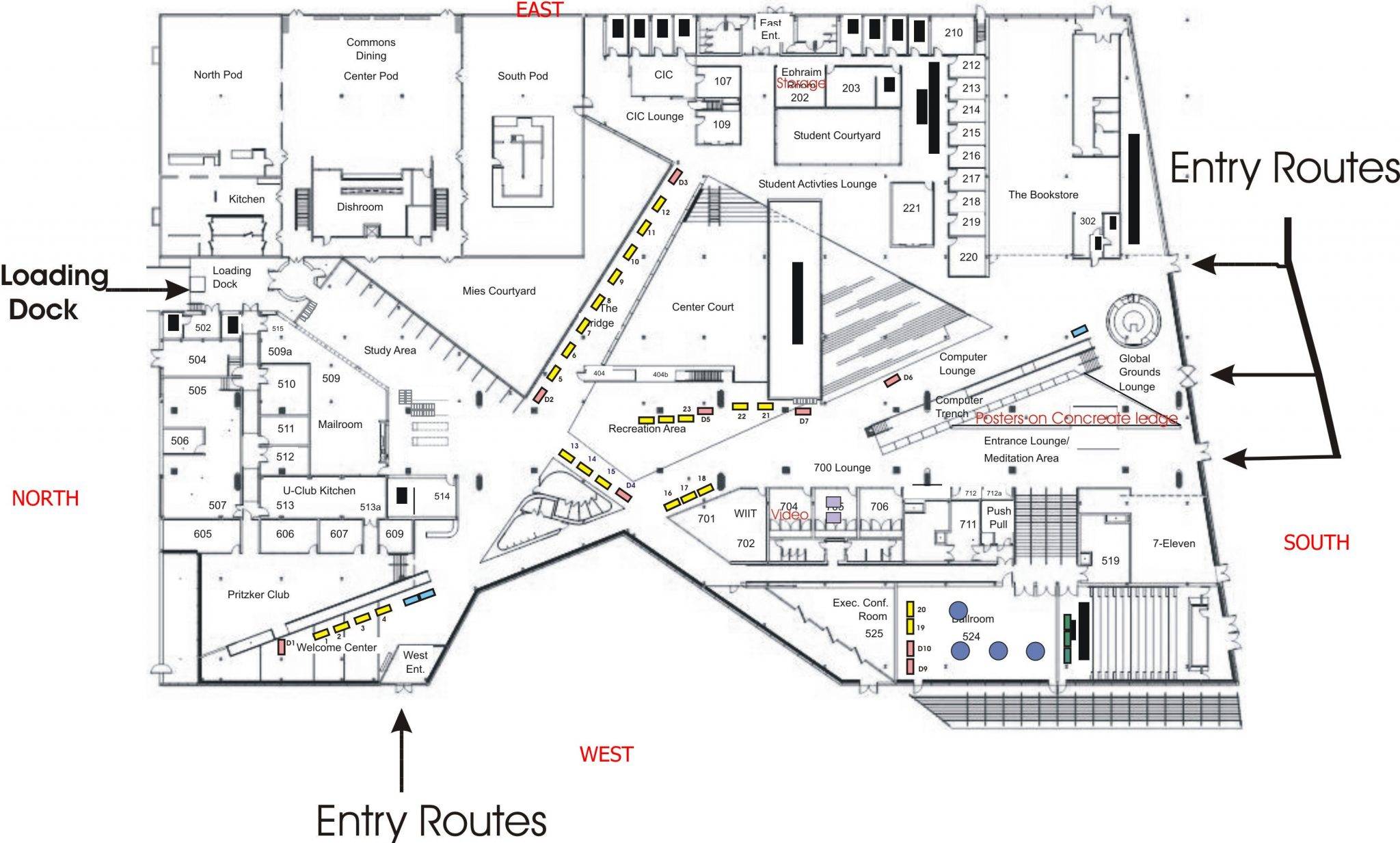

Given that his brief was to create a new building that serves as a central hub for student life and that he had already been offered an organic design blueprint for the way students used the campus, he decided to reflect this in the layout of the new building. The result is an irregular floor plan with diagonal corridors of differing widths linking the parts of the interior in a way that reflects the number of students who use the paths they create.

Rem Koolhaas’s organic design for the McCormick Center

He wasn’t the first person to eschew the rectangular order in favour of organic design based on the way people move around a building and interact with each other. In the 1950s, the Quickborner team in Hamburg, led by the brothers Eberhard and Wolfgang Schnelle, applied the egalitarian principles of the post war world coupled with a rejection of the scientific management theories that had created the familiar rows of desks associated with open plan offices up to that point to create something entirely new.

As with Rem Koolhaas’s appropriation of the movement of people across a field, the Quickborner’s idea of Bürolandschaft (office landscape) applied organic forms to create something they considered more human-centric and natural. The designs used conventional office furniture, but planned in an organic way, with space also divided up using plants and curved screens. One of the first firms to adopt the new principles to see how they worked as a way of improving communication and productivity was the publishing giant Bertelsmann at one of its office buildings in the town of Gütersloh.

The layout for Bild und Ton

[perfectpullquote align=”right” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]The anti-hierarchical lines of movement and communication, expressed in the irregular layout of the office was typical of a principle that quickly gained popularity but was doomed and in a profoundly ironic way[/perfectpullquote]

The anti-hierarchical lines of movement and communication, expressed in the irregular layout of the office was typical of a principle that quickly gained popularity but was doomed and in a profoundly ironic way. While many designers and office furniture makers picked up on the principles of Bürolandschaft, the gravitational pull of the rectilinear turned out to be to powerful a force to overcome.

In 1958, the same year that the brothers Schelle popularised Bürolandschaft the US office furniture giant Herman Miller recruited a designer called Robert Propst to design a new range of personal space for open plan offices. The resultant Action Office system (1964) came to define the open plan office in America as well as its equivalents in Europe. Although ostensibly the heirs to Bürolandschaft, these new systems with their right angles and serried, uniform ranks betrayed one of its core ideas.

Propst himself came to be seen as the Godfather of cubicles but he too was betrayed by what the corporate world made of his creation. He shared the Schelle’s yearning for egalitarianism and once bemoaned that ‘the cubiclizing of people in modern corporations is monolithic insanity’.

Half a century on from the creation of both Action Office and Bürolandschaft, the debate about this monolith continues. But we are seeing a return to the organic in the way many modern offices are designed to encourage and allow for people to move around and create their own pathways through the building.

First published in 2014.

___________________________

Paul Goodchild is the Design Director of Fresh Workspace.

January 31, 2022

From the archive: How organic design can reflect the way people move around a building

by Paul Goodchild • Comment, Workplace design

Given that his brief was to create a new building that serves as a central hub for student life and that he had already been offered an organic design blueprint for the way students used the campus, he decided to reflect this in the layout of the new building. The result is an irregular floor plan with diagonal corridors of differing widths linking the parts of the interior in a way that reflects the number of students who use the paths they create.

Rem Koolhaas’s organic design for the McCormick Center

He wasn’t the first person to eschew the rectangular order in favour of organic design based on the way people move around a building and interact with each other. In the 1950s, the Quickborner team in Hamburg, led by the brothers Eberhard and Wolfgang Schnelle, applied the egalitarian principles of the post war world coupled with a rejection of the scientific management theories that had created the familiar rows of desks associated with open plan offices up to that point to create something entirely new.

As with Rem Koolhaas’s appropriation of the movement of people across a field, the Quickborner’s idea of Bürolandschaft (office landscape) applied organic forms to create something they considered more human-centric and natural. The designs used conventional office furniture, but planned in an organic way, with space also divided up using plants and curved screens. One of the first firms to adopt the new principles to see how they worked as a way of improving communication and productivity was the publishing giant Bertelsmann at one of its office buildings in the town of Gütersloh.

The layout for Bild und Ton

[perfectpullquote align=”right” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]The anti-hierarchical lines of movement and communication, expressed in the irregular layout of the office was typical of a principle that quickly gained popularity but was doomed and in a profoundly ironic way[/perfectpullquote]

The anti-hierarchical lines of movement and communication, expressed in the irregular layout of the office was typical of a principle that quickly gained popularity but was doomed and in a profoundly ironic way. While many designers and office furniture makers picked up on the principles of Bürolandschaft, the gravitational pull of the rectilinear turned out to be to powerful a force to overcome.

In 1958, the same year that the brothers Schelle popularised Bürolandschaft the US office furniture giant Herman Miller recruited a designer called Robert Propst to design a new range of personal space for open plan offices. The resultant Action Office system (1964) came to define the open plan office in America as well as its equivalents in Europe. Although ostensibly the heirs to Bürolandschaft, these new systems with their right angles and serried, uniform ranks betrayed one of its core ideas.

Propst himself came to be seen as the Godfather of cubicles but he too was betrayed by what the corporate world made of his creation. He shared the Schelle’s yearning for egalitarianism and once bemoaned that ‘the cubiclizing of people in modern corporations is monolithic insanity’.

Half a century on from the creation of both Action Office and Bürolandschaft, the debate about this monolith continues. But we are seeing a return to the organic in the way many modern offices are designed to encourage and allow for people to move around and create their own pathways through the building.

First published in 2014.

___________________________

Paul Goodchild is the Design Director of Fresh Workspace.