June 5, 2020

The seven greatest depictions of the workplace in art. Possibly.

Art supposedly holds up a mirror to life. Except when it comes to our working lives, it doesn’t. Or at least it doesn’t always show a true or full reflection, both in terms of the amount of time we dedicate to work and how important it is to us.

Art supposedly holds up a mirror to life. Except when it comes to our working lives, it doesn’t. Or at least it doesn’t always show a true or full reflection, both in terms of the amount of time we dedicate to work and how important it is to us.

Most of us spend at least a quarter of our time each week at (or on our way to) work. Many of us struggle to escape it in our own time too. We worry about it when we shouldn’t. It pays our way. It helps to define who we are. It structures our time. It introduces us to friends and partners. Yet in spite of the crucial role it plays in our lives, there are precious few depictions of the workplace in art.

As is true of depiction of work in movies and music, it is almost invariably portrayed in a negative light, dehumanising drudgery replete with the potential for humiliation. Yet some artists have attempted to portray some of the complexities of work. These are some of my personal favourites.

May Day V

The photographer and artist Andreas Gursky is very much a man of our times in the way he documents the world and its people and places. Although Gursky’s work often focuses on the relationship between people and their surroundings, he himself has admitted he is not interested in the individual per se and nowhere is this more apparent than in May Day V.

He’s been knocked recently, notably because he is seen as ‘out of touch in the post 9/11 world’ according to one critic. But the world didn’t change completely on that day, life went on and the submersion and alienation of the individual in the modern world is an understandably persistent theme in American art in general and that of Gursky in particular. It is on display at the Matthew Marks Gallery, New York.

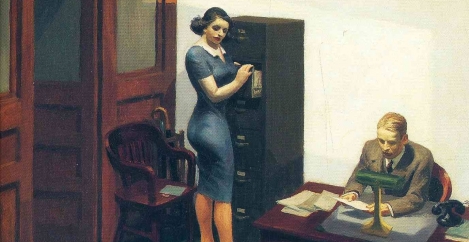

Office at Night

Hopper is part of the great tradition in art that explores the relationship between people and their environment. Office at Night is typical of the artist because it has an unmistakeable atmosphere and sense of narrative. It doesn’t tell a story exactly because Hopper raises questions for the viewer to ponder themselves.

Hopper is part of the great tradition in art that explores the relationship between people and their environment. Office at Night is typical of the artist because it has an unmistakeable atmosphere and sense of narrative. It doesn’t tell a story exactly because Hopper raises questions for the viewer to ponder themselves.

It invites us to decide for ourselves what is going on and write our own story about the people in the picture, their relationship and how the tensions between them are resolved. But this is Hopper and the conflicts between isolation and togetherness are often evident. It can be seen at the Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, Minnesota.

Zeichensaal

At first sight, Zeichensaal is a photograph of an office. In this case, the office of Richard Verhölzer, an architect from Munich who was important in the post war reconstruction of Germany. It takes a few seconds and close examination to realise it is in fact a photograph of a model of the office, carefully and painstakingly reconstructed by the artist Thomas Demand from an original image. It’s method is very post-modern. Like the work of Gursky it uses a trick to distance itself from reality. Whereas Gursky uses the digital manipulation of images, Demand reconstructs a real place to twist the perception of the viewer. It can be seen at Tate Liverpool.

At first sight, Zeichensaal is a photograph of an office. In this case, the office of Richard Verhölzer, an architect from Munich who was important in the post war reconstruction of Germany. It takes a few seconds and close examination to realise it is in fact a photograph of a model of the office, carefully and painstakingly reconstructed by the artist Thomas Demand from an original image. It’s method is very post-modern. Like the work of Gursky it uses a trick to distance itself from reality. Whereas Gursky uses the digital manipulation of images, Demand reconstructs a real place to twist the perception of the viewer. It can be seen at Tate Liverpool.

Work

The 19th Century painter Ford Madox Brown’s Work depicts a London street scene at a time of enormous social upheaval. Its Hogarthian cast of characters including navvies, an orange seller, MP, street urchin with baby and vicar convey the class system of the day in the setting of a typical London street scene.

The 19th Century painter Ford Madox Brown’s Work depicts a London street scene at a time of enormous social upheaval. Its Hogarthian cast of characters including navvies, an orange seller, MP, street urchin with baby and vicar convey the class system of the day in the setting of a typical London street scene.

The painting also depicts the social upheaval of the time, not least in the way people had been thrown into the melting pot of the city to either flourish or eke out an existence with lives defined by what they did. It was completed in 1865 as the British population was undergoing the shift to urban life in the wake of the Industrial Revolution. Work can be seen at the Manchester Art Gallery.

Crane and Ships, Glasgow Docks

Although normally associated with the grimy and nostalgically romantic surroundings and lives of people in towns in the North West of England, in Cranes and Ships, L S Lowry depicted the docks on the River Clyde at Glasgow in his unmistakable style. Now in the possession of the City of Glasgow and on display at the Riverside Museum, it was painted in 1947 as the world was recovering from the War and is a typical Lowry depiction of life in a grey industrial town. Although the ships and cranes are important elements in the painting, nobody is actually doing any work. The familiar Lowry figures in the foreground appear to be walking and talking, possibly between jobs.

Although normally associated with the grimy and nostalgically romantic surroundings and lives of people in towns in the North West of England, in Cranes and Ships, L S Lowry depicted the docks on the River Clyde at Glasgow in his unmistakable style. Now in the possession of the City of Glasgow and on display at the Riverside Museum, it was painted in 1947 as the world was recovering from the War and is a typical Lowry depiction of life in a grey industrial town. Although the ships and cranes are important elements in the painting, nobody is actually doing any work. The familiar Lowry figures in the foreground appear to be walking and talking, possibly between jobs.

Underwater sculpture

Jason de Caires Taylor gained recognition in 2006 when he created the world’s first underwater sculpture park in Grenada. The sculptures are situated in fairly shallow and clear waters on a coral reef to allow divers and snorkellers the chance to explore them. As well as engaging pieces in their own right, their siting also means that over time they will be colonised and devoured by coral, inherently ephemeral and attuned to nature. The figure of the man at his desk gamely plugging on with his work has an otherworldly feel.

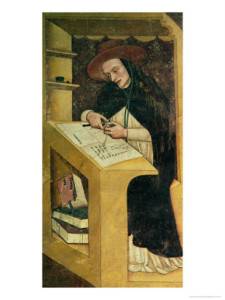

Forty Dominicans at their Desks

Dominican friars first arrived at Treviso in Northern Italy in the 13th Century, where they founded the Church of San Nicolò. In the mid 14th Century they commissioned the artist Tomaso da Modena to create a fresco in the chapter room of the church depicting forty famous monks of the order in their cells and hard at it at their desks.

Dominican friars first arrived at Treviso in Northern Italy in the 13th Century, where they founded the Church of San Nicolò. In the mid 14th Century they commissioned the artist Tomaso da Modena to create a fresco in the chapter room of the church depicting forty famous monks of the order in their cells and hard at it at their desks.

Cloistered life lends itself to focussing on meeting a string of often menial tasks and if it wasn’t for the monastic garb they look for all the world like they would fit straight in to a modern office.