May 29, 2019

Biophilia in the corporate HQ: an historical perspective

In recent years, the concept of biophilia and the inclusion of greenery in the working environment has captured the media’s attention, which has depicted it as an important aspect of wellbeing in the workplace, seemingly the crucial indicator of a great office. For this reason, and beyond the superficial or cosmetic use of plants in the office, I would like to analyse the relationship between nature and the corporate world from a historical perspective in an effort to understand the role of greenery within the architecture of the corporate headquarters.

In recent years, the concept of biophilia and the inclusion of greenery in the working environment has captured the media’s attention, which has depicted it as an important aspect of wellbeing in the workplace, seemingly the crucial indicator of a great office. For this reason, and beyond the superficial or cosmetic use of plants in the office, I would like to analyse the relationship between nature and the corporate world from a historical perspective in an effort to understand the role of greenery within the architecture of the corporate headquarters.

Professor Louise Mozingo´s Pastoral Capitalism; A History of Suburban Corporate Landscapes has been absolutely essential in this regard, along with other related texts such asThe Company Town by Hardy Green, Company Towns in the Americas edited by Angela Vergara and Oliver Dinius, and Building the Workingman´s Paradise; The Design of American Company Towns by Margaret Crawford, which have all been essential in providing the author with a broader perspective on the topic.

These texts shed light on to the current use of nature in the context of corporate offices being built for tech “unicorns”, especially in the United States, the focus of this text, allowing us to learn from the current situation from an historical perspective.

This study identifies three consecutive ways nature has been utilised within the corporate HQ. In identifying these three models, we highlight the concept of “utilization”, since one of the conclusions of the study is that nature has been used by the corporate world at different times with different intentions.

These three models are:

- The first, EXTRACTION, relates to the original American company towns, where nature was simply the place from where raw materials were extracted or obtained through mining or industrial processes.

- The second, REPRESENTATION, refers to the time when green meant good and companies were able to greenwash the corporate conscience while providing pastoral environments for the post II World War multinational corporations.

- The third, which we will call ARTIFICIALIZATION, is the more recent utilisation of nature we are seeing by the large tech and social media companies, where nature is confined within a highly controlled architectural and artificial environment.

Extraction

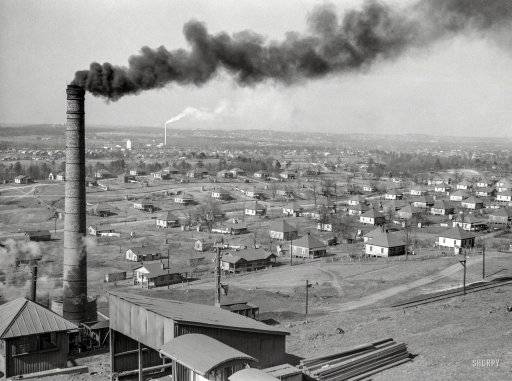

Many of the first company towns appeared in the late 19th Century as coal mining communities, and were consequently built around the mines and extraction areas. The conditions of these company towns varied hugely depending on each company and site, but were generally understood as a way of limiting union

February 1937. “Company steel town”. Jefferson County, Alabama. Photo by Arthur Rothstein, Resettlement Administration

power and providing a paternalist environment where blue collar workers would spent their income wisely, rather than “… sending it down your throats in the form of bottles of whisky, bags of sweets, or fat geese at Christmas” as the founders of Port Sunlight in the United Kingdom used to say to their employees. It goes without saying that income was typically provided in scrip, a crypto currency that could only be spent in the local company store.

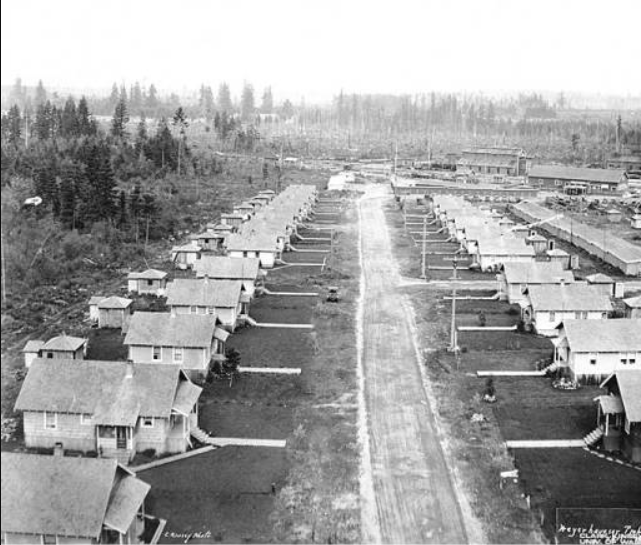

Nature in those days was the source of raw materials and where a basic urbanism had to be applied in order to create the right conditions for the workers. Many of them installed sewers and paved roads and eventually amenities such as schools, swimming pools, social clubs and even hospitals, whilst many others were little more than concentration/labor camps. Some of the first eventually evolved into proper cities, like Jenkins in Kentucky, Holden in Virginia or Kannapolis, a company town built by Cannon Mills, or even Gary, Indianapolis, which took its name after the Chairman of US Steel, the company that had created the town. Other examples include UK chocolate maker Cadbury´s Bourneville in the English midlands.

As well as mining, there were other kinds of company towns, where agriculture, cotton, sugar cane or logging were the main activities.

The character of these extractive settlements was industrial; the machinery, piping and chimneys signposted the industrial activities taking place there. Urbanisation, road-building and housing were generally not respectful of the landscape and surfaces were levelled and trees chopped down for roads and houses to be built.

These company towns saw nature as a place from which to extract raw materials and to dump the industrial waste, generally without any type of control.

Representation

In the aftermath of World War II, the North America saw the birth and development of large corporations, later named multinationals, which grew exponentially in parallel with the appearance of mass produced consumer goods.

Deere & Company Administrative Center. Arq. Eero Sarinen. Completion 1963. Photo Ezra Stoller/ Esto/Flickr Creative Commons license

Many of these companies where originally located in the central business districts of major US cities, where their top managers and factories co-existed. With the progression of capitalist management methodologies and the need for more advanced and sophisticated research and development facilities, companies started the process known as the corporate exodus to the suburbs, where they were to find an appropriate environment for their new facilities. There were many reasons for this exodus beyond the need for space; they include industrial secrecy and safety, along with fears of a Soviet nuclear attack on the main cities.

The central business districts hadn’t been planned along modernist lines, so expectations of a corporate campus in the suburbs responded to the dream of “…orderliness, spaciousness and well-being” so well explained by Professor Mozingo in her seminal Pastoral Capitalism. This pastoral condition is what we understand as the REPRESENTATION type of relationship with nature, what companies and media alike identified as “untouched” nature and the representation of certain values that the corporations wanted to endorse in order to deliver a message of wellbeing to a society that was becoming more and more conscious of corporate power. The relationship with one of the more authentic and original American creations, the college campus, was also part of this equation, where corporate research could be identified with non-for-profit activities: socially aware academic research to which academics were originally drawn to.

The suburban pastoral landscape was no longer about extraction: research and development facilities had no chimneys, instead resembling universities and colleges where “talented young men are encouraged to think freely”. Company towns were no longer labour camps and nature was now a way of representing new values such as sharing knowledge for the public good.

From the 1950s through to the end of the century, many US corporations built large corporate campuses or estates based on the same principles; low rise buildings set innocently amid a pastoral landscape with trees, lakes, ponds and hills. Facilities such as the GM Technical Center in Warren, built in 1956, the General Electric Campus in Schenectady or the AT&T Bell Laboratories in Summit, NJ, embodied this new type of relationship with nature to create idyllic, sublime environments that utilised nature as a way of endorsing new values related to social corporate responsibility and wellbeing for employees and, later on, environmentalism, which also became part of the equation some decades after.

This model of the pastoral corporate campus was exported globally and many of the original US-based architects designed large facilities across the glob using the same principles and values which were widely accepted as the norm for large suburban facilities until the end of the century.

Artificialisation

The rise of the knowledge economy and the information revolution based on the internet and IT has produced the appearance of a third type of relationship with nature which we initially describe as artificialisation, since we understand that nature is utilised in a much more controlled, artificial way in the previous types.

[perfectpullquote align=”right” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]Nature is utilised in a much more controlled, artificial way[/perfectpullquote]

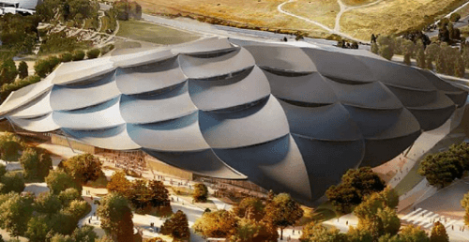

This conclusion is based on the latest corporate HQs being built for three major tech companies; Apple, Amazon and Google, all of them in the United States. Each is radically different, but similar in their highly controlled depiction of nature, which becomes almost an artificial tool to convey a message of power and control.

In the first of the examples, Amazon’s HQ in Seattle by NBBJ Architects, consists of two high rise, standard office buildings with two geodesic spheres at the ground level which include a green ecosystem with a plethora of plants and exotic greenery, which clearly couldn’t survive unaided in Seattle’s chilly weather.

The two spheres act as a semi-public realm where visitors and employees can mingle and work informally in a fully controlled environment with temperature and humidity fully independent of exterior conditions.

Another large corporate GQ attracting huge media attention is the Apple HQ in Cupertino, which consists of a three-storey building in the shape of a perfect circle which seems to contain, in its interior, a pristine landscape evoking the nearby Purisima Creek Redwoods Open Reserve to the West of Apple Park, beyond the highly urbanized, low density immediate environment around the building.

What this (very telling) picture is saying is that the circular building is somehow preserving nature in its original state, in the way it was before urbanisation came along. The building is therefore creating an artificial environment that outsiders are no longer able to enjoy, recalling a time when trees and greenery formed an untouched, virgin American landscape.

The third example of this artificialisation strategy is the Google HQ by Heatherwick Studio and BIG Architects in Mountain View. Recently released images show a landscape of low-rise buildings covered by what seems to be a textile, semi-transparent and permeable fabric. Images and descriptions of this fabric have changed in the last months and vary enormously in what seem to be a complex and sophisticated exercise of artificialisation.

The architectural strategy seems to be the creation of a semi-interior environment which combines the blessings of Californian weather with the benefits of a highly controlled atmosphere. The images seem a little bit tricky, though. Wouldn’t it have been easier to just create an outdoors, campus-like environment around the low rise buildings, immersed in greenery and informal working environments? The objective seems to be to create this artificial environment which is neither interior or exterior, but instead both at the same time. The resulting atmosphere is yet to be experienced and understood. In any case, it is clearly a highly controlled environment that will create an artificial environment to be enjoyed by employees and visitors alike, but not by neighbours, who will instead see a massive tent-like structure over a hidden landscape or buildings and greenery.

Conclusions

What seems clear from this overview of the different uses of nature within corporate HQs and office buildings throughout the 20th Century is that nature and greenery have always been utilized as a tool by corporations to obtain their business objectives. This utilisation has taken many aspects; either by extracting raw materials, creating a pastoral landmark and ultimately by demonstrating power and control over the world by the creation of extremely sophisticated and artificial environments around their offices.

All of these strategies can be framed within the larger modernist debate over the creation of ex-novo cities and master planning from scratch, where architects and urbanists alike have the chance to create a new, utopian world. The successive manipulation of nature included in these strategies has gone from extraction through artificialisation, as If nature “as it is” weren’t good enough for humans to work in. Despite the general acceptance that greenery improves productivity and wellbeing in the workplace, corporations keep on defining highly artificial and controlled semi-natural environments that hark back to classic idea of happy arcadia, either by pastoral means or by high-tech interventions.

The relation between “green” and “happiness” is being forced to the extreme, building artificial, greenhouse like structures that create environments where the weather will be more similar to foreign latitudes but with western levels of comfort and safety. In our opinion the idea of the search for exotism and even orientalism can also be traced here as part of these artificialization strategies.

In conclusion, it will be extremely interesting to see the output of these post utopian environments, where nature is been pushed into the next level of human manipulation in the search for a highly controlled and engineered workplace. Only time will tell if these environments truly foster wellbeing, productivity and social, corporate responsibility.

_______________________________________

Guzmán de Yarza Blache is EMEA Head of Workplace Strategy at JLL. He is also the Academic Director of the Master in Strategic Design of Spaces at the IE School of Architecture and Design, an international graduate program designed in partnership with the Royal College of Art in London that is educating professionals in design strategies that can create spaces that foster change and innovation.