July 29, 2024

A large pay gap between business leaders and staff is bad news for businesses

Employees may be less productive and have more negative emotional experiences at work when there is a large pay gap between them and those in leadership roles, a new study shows. The ‘vertical pay gap’ between leaders and other employees has been found to have risen markedly over the past five decades.

Employees may be less productive and have more negative emotional experiences at work when there is a large pay gap between them and those in leadership roles, a new study shows. The ‘vertical pay gap’ between leaders and other employees has been found to have risen markedly over the past five decades.

The new study, published in The Leadership Quarterly, claims to show for the first time that these pay gaps may make employees less willing to carry out what is asked of them or work for the good of their firm.

Researchers from the University of Exeter Business School recruited 650 participants to take part in a pre-registered randomised experiment designed to reveal the impact of pay differentials on workers’ attitudes and behaviours.

The experiment simulated a real life work situation: the participants were put into groups of three with one leader and two subordinate workers. The workers were given a task to complete, with a payment structure which included bonuses for successful work carried out.

The salary of leaders, whose job it was to supervise and offer feedback, was 10 times more than that of workers. The leaders’ bonus – determined by how well the workers completed their task – varied: in the small pay differential condition their bonus was the same as the workers’, but in the large gap condition leaders received a bonus 10 times greater than that received by workers (a discrepancy that mirrors an estimate of CEO to worker pay ratio).

The study also tested how the source of this pay gap impacted on worker behaviour: for half the participants the gap was fixed and outside of the leader’s control (a condition that mirrors the effect of pay being determined by an external source such as a board). For the rest of the participants, the leader had some choice over the size of their own bonus.

Participants then completed a survey about their organisation and leader, which asked questions about their organisational identification and their emotional wellbeing, as well as their feelings towards their leader.

The researchers found that workers were less productive and less inclined to contribute to the good of the company when working for a firm where there was a large pay gap that was chosen by the leader.

However, when the large pay gap was imposed by an external source this had no impact on the workers’ production.

The study also found that workers in the large pay gap condition were less satisfied with their pay and identified less with both their organisation and leader.

The link between leaders giving instructions for workers to increase their output and production increasing was also found to be weaker when the pay gap was large. Workers in the large gap condition also reported finding their leaders less ‘elevating’ and feeling a greater sense of outrage towards them, as well as reporting a lower sense of emotional well-being.

Kim Peters, Professor in Human Resource Management at the University of Exeter Business School and lead author of the study said: “The vertical pay gap matters. Larger gaps cause psychological divisions within the workforce and create fertile soil for ‘us’ versus ‘them’ dynamics between the organisational haves and the have nots.

“One lesson that leaders who wish to increase the size of the vertical pay gap in their organisation could draw from these findings is that they could reduce the risk of adverse employee behaviour by using compensation committees or external consultants.

“For the many organisations and leaders who have already learned this lesson, we would instead draw their attention to our finding that a large vertical pay gap has negative implications for employees’ emotional well-being.”

“Do followers mind the pay gap? An experimental test of the impact of the vertical pay gap on leader effectiveness” is published in The Leadership Quarterly and is co-authored by Professor Kim Peters, Professor Miguel Fonseca and Professor Oliver Hauser from the University of Exeter Business School and Professor Nik Steffens from the University of Queensland.

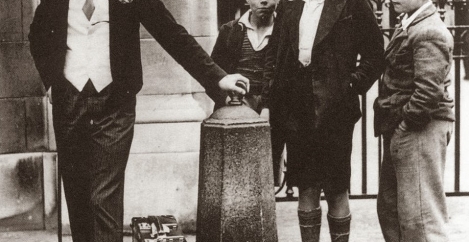

Image: Toffs and Toughs, 1937 by Jimmy Sime