February 15, 2019

Amazon drops plans for HQ, judging others in the open plan, why people would rather electrocute themselves than sit and think and some other stuff

Why is it so hard to design a decent office space? demands this article in Quartz. It’s a fair enough question but probably the wrong one. It’s perfectly possible to design a decent (or adequate) office with a pen, paper and bag of presuppositions and many people have done exactly that. The real question is why it is so hard to design a good or excellent office.

It’s a point addressed in this blog from The Right Ubiquitous Neil Usher who argues firstly that things are complicated (obv.) and that our fixation with meeting the needs of ‘the individual’ can blind us to some truths about what makes a workplace excel for the organisation and everybody in it. It’s not so much the models of design we use that are the problem as the way we think about them and the job we want them to do. He also issues a plea for an end to the backlash against the backlash to open plan. “The ‘open plan’ beat-up is an irrelevant distraction, ignore it, don’t get involved”, he implores.

And of course, neither the backlash nor the backlash to the backlash will stop. It’s relentless. The Quartz article is often interesting but also sometimes burdened with the usual layers of irrelevance, generalisation, apex thinking, misinformation and assumptions that characterise the widely argued critique of open plan offices. This is not really a point in favour of the open plan, but whatever side of the argument you are on, it probably exhibits less of a commitment to command and control than the idea of corporate drones checking what people are doing, regardless of the good intentions behind them.

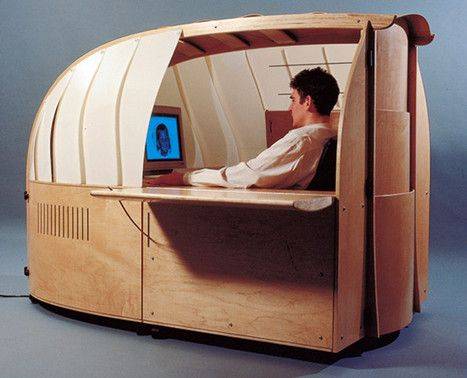

It wouldn’t be a week in the great open plan non-debate without some contribution from Fast Company or Inc and sure enough here’s a piece in the former suggesting that we are all prone to judge others when we have sight of them. So, the ability to see them, for example in an open plan office, makes the process of judging easier and therefore more frequent. Duh, you might say – and you’d be right – but pieces like this always beg the question of the alternative. Maybe it’s time to rehabilitate Douglas Ball’s Clipper workstation idea from the 1990s.

It wouldn’t be a week in the great open plan non-debate without some contribution from Fast Company or Inc and sure enough here’s a piece in the former suggesting that we are all prone to judge others when we have sight of them. So, the ability to see them, for example in an open plan office, makes the process of judging easier and therefore more frequent. Duh, you might say – and you’d be right – but pieces like this always beg the question of the alternative. Maybe it’s time to rehabilitate Douglas Ball’s Clipper workstation idea from the 1990s.

As ever the complicating factor is people. They’re a pain in the neck sometimes, prone to irrationality and often make things far more difficult than they really should be, yet we still like being around them. Neil Usher’s blog argues against the potential counterproductivity of what he calls enforced agility in the office and a related point is raised in this piece in the FT (registration). It argues that, despite the wider use of flexible working in its various forms, people often still like to go to the office and firms are often glad to see them there. You can build it but they may not come.

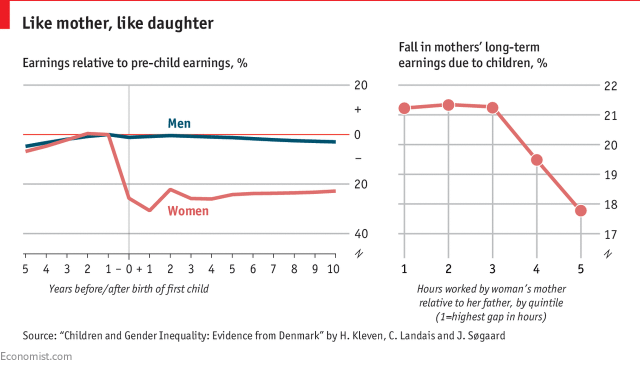

One area in which flexible working does offer demonstrable benefits is in the careers and incomes of parents and especially mothers. This piece in The Economist demonstrates the cliff edge they face when they have children. Worth noting that British women at least now outearn men in the same role at a specific point in their careers before they become parents, according to official government stats. At the risk of mansplaining, it seems pretty obvious where efforts to address the difference in earnings between men and women should be focused.

One of the reasons we might have an ambivalent attitude towards flexible working may be hardwired. This piece in Aeon reports, amongst other things, that far more people than you might assume would rather electrocute themselves than sit alone in quiet contemplation. We all have these ghosts in us however much we think we understand ourselves and how we function as rational beings. So maybe the Clipper should stay in the archive after all.

The question of our shortcomings and complications and their effects on building design is addressed in this longer piece from David Marshall who asks how we can model buildings to gauge how people will respond to them, not least because architects appear to have lost sight of the fact that buildings are there to serve the people in and around them. Architects might argue with this characterisation, but they might also pause to consider why so many people believe it.

Who is responsible when a building performs poorly? How long do we wait to find out? How do we trace performance back to design, construction, and operations or some combination thereof? How is it remedied? Who pays for the remedy? What happens when my definition of “performs poorly” is different from yours? American architects stepped away from questions like these during the course of the 20th century, perhaps due to scary questions like legal liability, so it’s no surprise that much of the current output by architects is still perceived as not responding directly enough to human needs. It’s not just architects, of course. Developers and large-scale builders have also structured the delivery of new buildings in such a way that accountability is a hot potato. Failures are often better unacknowledged than accepted and dealt with. Truly human-centered architecture may not be possible without also rethinking the way that we finance, insure, permit, build, and operate buildings. For all parties involved, it’s hard to imagine being human-centered without a little skin in the game.

Finally, Amazon continues to do whatever it can to annoy the hell out of everybody. It has announced that it has dropped plans to create a £2.5 billion HQ in New York after it had given a number of US cities the run around for over a year. The bidding process for the office saw it receive pitches from 238 cities in the US and Canada with 20 finalists abasing themselves in an attempt to woo the firm with tax breaks and sweeteners.