July 25, 2019

One dishonest co-worker can disrupt an entire workplace

A vicious cycle can begin with one little white lie from a co-worker, diminishing the ability of other employees to read others and then even undermining the entire workplace or business, finds a new study from researchers at Michigan, Harvard, Virginia and Olin Business School at Washington University in St. Louis. Dishonest deeds diminish a person’s ability to read others’ emotions, or “interpersonal cognition,” the research found. In addition, the consequences can snowball. One dishonest act can set in motion even more dishonesty.

A vicious cycle can begin with one little white lie from a co-worker, diminishing the ability of other employees to read others and then even undermining the entire workplace or business, finds a new study from researchers at Michigan, Harvard, Virginia and Olin Business School at Washington University in St. Louis. Dishonest deeds diminish a person’s ability to read others’ emotions, or “interpersonal cognition,” the research found. In addition, the consequences can snowball. One dishonest act can set in motion even more dishonesty.

Dishonesty has repercussions beyond harming trust and the reputation of a co-worker if others become aware of it, according to the study, “The interpersonal costs of dishonesty: How dishonest behavior reduces individuals’ ability to read others’ emotions,” published in the Journal of Experimental Psychology: General.

Such behaviour by employees is estimated to come at a $3.7 trillion cost annually worldwide. Lying and cheating is “not only is financially costly (as in the case of stealing from a company, for example, or increasing the risk of costly lawsuits) but also can harm interpersonal relationships through a particular channel: individuals’ ability to detect others’ emotions,” even when those others are not the victims of the wrongdoing.

The report concludes that it’s no surprise that a co-worker who lies and cheats liars can hurt the workplace, as well.“It can be a vicious cycle,” said Ashley E. Hardin, assistant professor of organisational behaviour at Olin. “Sometimes people will tell a white lie and think it’s not a big deal. But a decision to be dishonest in one moment will have implications for how you interact with people subsequently. Given the rise of group work in organisations, there’s a heightened awareness of the importance of understanding others’ emotions.”

Hardin’s areas of expertise are organisational behaviour, team development and negotiation. The research was conducted with Julia J. Lee of the University of Michigan; Bidhan Parmar of the University of Virginia; and Francesca Gino of Harvard University.

A vicious cycle

[perfectpullquote align=”right” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]The findings fundamentally challenge views that lump morality and empathy into a single construct[/perfectpullquote]

In all, the researchers conducted eight studies involving more than 1,500 adults to gauge lying and cheating in various scenarios. The findings support the following:

- A connection exists between dishonest behaviour and one’s ability to accurately read and empathise with the emotions of a co-worker.

- Bad actors are less likely than others to define themselves in terms of close relationships, for example as a sister or a mentor.

- Dishonest behaviour leads to damage downstream; the first transgression is a catalyst to dehumanise others and perform even more dishonest acts.

- People who are more socially attuned are less likely to behave dishonestly.

“When individuals are lacking their physiological capacity for social sensitivity, they may be more susceptible to the social distancing effects of engaging in dishonest behaviour,” the researchers wrote.

The findings fundamentally challenge views that lump morality and empathy into a single construct, Hardin said. Social psychology research has long argued that empathy is a moral sentiment that triggers prosocial behaviour. But empathy toward others can also lead employees to cross ethical boundaries.

Consider a 2010 study by Olin’s Lamar Pierce, professor of organisation & strategy at Olin and associate dean for Olin-Brookings Partnership, and Gino, then at the University of North Carolina. The research was in the context of vehicle emissions. Employees helped customers with standard vehicles, as opposed to luxury cars, by illegally passing the cars on emissions tests. The results suggested that empathy toward others with a similar economic status can motivate dishonest behaviour. Basically, the findings highlighted the importance of social context in ethical decision-making.

“Our work adds to this dynamic tension between dishonesty and empathy by showing. … that one’s empathic accuracy can be affected by the specific psychological state produced by one’s dishonest behaviour,” the researchers wrote.

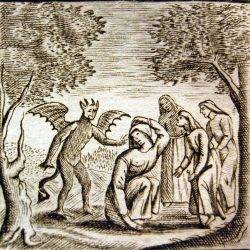

Image: The devil takes the hindmost. An illustration from Joseph Glanvill’s Saducismus Triumphatus