June 12, 2025

Turns out that hybrid working is indeed the new normal. For a minority of people

A new analysis from the Office for National Statistics confirms that hybrid working is now the dominant form of flexible work for many people in Great Britain. The figures, which cover the period from January to March 2025, show that 28 percent of working adults now combine home and on-site work on a regular basis – the highest proportion recorded since the ONS began monitoring hybrid working patterns. This compares with just 9 percent who work exclusively from home and around 55 percent who are permanently based at a single workplace. The remaining proportion are made up of those with no fixed place of work or whose work locations vary, such as mobile or site-based roles.

A new analysis from the Office for National Statistics confirms that hybrid working is now the dominant form of flexible work for many people in Great Britain. The figures, which cover the period from January to March 2025, show that 28 percent of working adults now combine home and on-site work on a regular basis – the highest proportion recorded since the ONS began monitoring hybrid working patterns. This compares with just 9 percent who work exclusively from home and around 55 percent who are permanently based at a single workplace. The remaining proportion are made up of those with no fixed place of work or whose work locations vary, such as mobile or site-based roles.

The figures reflect the extent to which hybrid working has become embedded as a lasting legacy of the pandemic, particularly among professional and knowledge-based occupations. However, they also highlight enduring disparities in who is able to access this way of working, with variations across age, income, occupation, education level, disability status and geography.

Age and occupation

Workers aged between 30 and 49 remain the most likely to work in a hybrid way, with over a third in this age bracket following a mixed pattern of home and workplace-based activity. This compares to 19 percent of those aged 16 to 29, and 24 percent of those aged between 50 and 69.

There is a clear distinction between occupational categories. Almost half of all employees in professional and managerial roles now work hybrid, whereas those in so-called elementary occupations – such as retail assistants, cleaners and manual labourers – remain far less likely to have access to flexible working. In these roles, just 3 to 4 percent reported working hybrid, and around 90 percent continue to work exclusively on-site.

Income and education

There is also a strong correlation between income and access to hybrid working. Employees earning £50,000 or more are more than five times as likely to work hybrid as those earning less than £20,000. This is in part due to the types of roles available to higher earners, but it also reflects differences in access to technology, autonomy and employer policy.

Education level appears to be a similarly significant factor. More than a third of people educated to degree level or above work in a hybrid way, compared with just 3 percent of those with no formal qualifications.

The ONS notes that people in lower-income or less skilled roles are also less likely to be offered any form of homeworking, with fewer employers providing the necessary support or infrastructure. As a result, employees in these groups often have more rigid work routines and fewer opportunities for flexibility, even where their personal circumstances might suggest a need for it.

Disability and geography

Disabled people are slightly less likely to work in a hybrid pattern than non-disabled people, with 24 percent doing so compared to 29 percent of their non-disabled peers. This difference is linked to the fact that disabled workers are more likely to work in lower-paid or part-time roles, where hybrid working is less common.

The data also highlights a regional and social divide in access to flexibility. People living in the least deprived areas of England are significantly more likely to work hybrid than those in the most deprived. In areas of low deprivation, 32 percent of workers are hybrid, compared with 24 percent in areas of high deprivation.

This suggests that hybrid working is more prevalent in places with higher concentrations of white-collar roles, and that efforts to extend flexible working more broadly remain constrained by the structure of local labour markets.

A lasting shift

While the total number of people working exclusively from home has declined steadily over the past two years, hybrid working appears to have stabilised as the new normal for a large part of the workforce. The balance between flexibility, location and productivity continues to be shaped by sectoral norms, employer expectations and job design.

The figures underline how hybrid working has matured into a sustained trend rather than a temporary adjustment, with many organisations embedding it as standard practice. However, they also reinforce the view that this shift has not been universal. For large parts of the workforce, particularly those in manual, service or frontline roles, the ability to work flexibly remains limited.

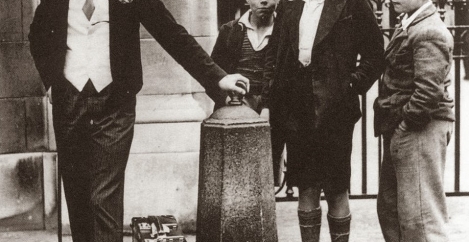

Image: Toffs and Toughs, 1937 by Jimmy Sime