In the 18th Century the utilitarian philosopher Jeremy Bentham came up with his idea of the Panopticon, a prison building with a central tower encircled by cells so that each person in the cells knew they could be watched at all times. Whether they were observed or not was actually immaterial. Bentham called it ‘a new mode of obtaining power of mind over mind’ and while he focused on its use as a prison, he was also aware of the idea’s usefulness for schools, asylums and hospitals. Bentham got the original idea following a visit to Belarus to see his brother who was managing sites there and had used the idea of a circular building at the centre of an industrial compound to allow a small number of managers to oversee the activities of a large workforce. This is something of a precursor of the scientific management theories of Frederick Taylor that continue to influence the way we work and manage people.

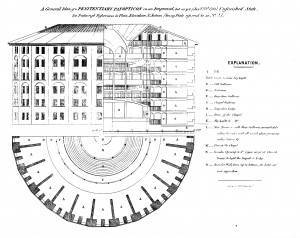

Indeed the layout of the Panopticon from Bentham’s original work – reproduced below – bears more than a passing resemblance to a contemporary open plan office building. Indeed Bentham’s description of the benefits of the Panopticon is like a rallying call for the apparent benefits of the open plan.

Morals reformed—health preserved—industry invigorated—instruction diffused—public burthens lightened—Economy seated, as it were, upon a rock—the Gordian knot of the poor-law not cut, but untied—all by a simple idea in architecture!

The idea has an enduring appeal. Michel Foucault did most to reapply the thinking behind the panopticon to 20th Century command and control structures in his 1975 book Discipline and Punish, in which he wrote “the Panopticon is a marvelous machine which, whatever use one may wish to put it to, produces homogeneous effects of power”. Just as Bentham had drawn inspiration for his idea from a work setting, so Foucault suggested that the idea as applied to prisons was a reflection of how the outside world functioned. This thinking is explicit in one of the Panopticon’s most famous practical examples, the ‘Model Prison’ in Cuba pictured in the header.

The symbolic and enduring appeal of the Panopticon is also applied to the technological surveillance of employees by the author Simon Head in his book Mindless: Why Smarter Machines Are Making Dumber Humans, in which he explores the consequences of a business culture still in the grip of scientific management thinking, albeit talking as if it weren’t, but now with the technological wherewithal to apply it to minutely observe, regiment and (increasingly) automate the work people do and the way they go about it.

The symbolic and enduring appeal of the Panopticon is also applied to the technological surveillance of employees by the author Simon Head in his book Mindless: Why Smarter Machines Are Making Dumber Humans, in which he explores the consequences of a business culture still in the grip of scientific management thinking, albeit talking as if it weren’t, but now with the technological wherewithal to apply it to minutely observe, regiment and (increasingly) automate the work people do and the way they go about it.

Perhaps this ability to mimic the open plan’s all-seeing eye in virtual space will drive the uptake of flexible working, or it may be just another tool of observation along with the building itself. Either way, our enduring love affair with the Panopticon in all its guises shows we are yet to reject the principles of scientific management. The most obvious contemporary manifestation of scientific management and the Panopticon itself is the open plan office.

In fact, there are many reasons why organisations like open plan offices beyond a simple impulse to watch people. When it comes to making the business case for them however, firms prefer to talk about some more than others. So while they prefer to focus on the argument in terms of how openness can foster better lines of communication, collaboration, teamwork and team spirit, they talk rather less about the fact that the open plan is a lot cheaper than its alternatives and how they like it because it allows them to keep an eye on what people are doing.

In theory at least, a great deal more of this surveillance now happens electronically so the need for physical presence should be less pressing, but the residual desire to see with one’s own eyes what people are doing remains. This is the instinct that constrains the uptake of flexible working and also means that there is a hierarchical divide in who gets to decide where they work. Practically all UK employees now have an equal right to request flexible working. But some are clearly more equal than others. A 2013 survey of 2,000 UK office workers by OnePoll found that 59 percent of senior staff were granted flexible working privileges compared to just 26 percent of those working lower down in the organisation.

The legal sector gives a particularly good example of how this manifests itself in practice. A recent survey of 3,400 solicitors carried out by the Law Society of Scotland found an increasing number were making use of flexible working. The research shows that while the majority of respondents (77 percent) continue to work full time, two thirds are now allowed to work away from their main place of work. In marked contrast to other professions, around two thirds of respondents did not access emails and work files while away from the office. Amongst the other interesting results from the survey is the fact that men are significantly more likely to be allowed to work from home than women (69 percent compared to 56 percent respectively) or work remotely (66 percent males compared to 51 percent of women).

This discrepancy may be a structural issue according to the report given that female employees in the legal profession have a tendency to fall into the £15,000 to £45,000 salary range whereas male employees are more likely to earn between £65,000 and £150,000 because women are more likely to be employed as administrators, trainees, associates and so on while men are more likely to be partners or directors.

At the heart of these status distinctions, there is evidently a degree of trust involved in the way firms not only offer employees flexible working arrangements but also their fondness for the open plan. Managers like to observe staff, but in return staff react to observation. We all understand that people act differently when they think they are being observed and it’s a characteristic that has been applied in interesting ways down the ages. Anybody interested in exploring the complex issues around open plan should have a listen to this fantastic programme on the BBC hosted by Julian Treasure.

Image: Friman, via Wikimedia Commons

December 12, 2017

A 300 year old idea explains some of the enduring appeal of the open plan

by Mark Eltringham • Comment, Facilities management, Workplace design

In the 18th Century the utilitarian philosopher Jeremy Bentham came up with his idea of the Panopticon, a prison building with a central tower encircled by cells so that each person in the cells knew they could be watched at all times. Whether they were observed or not was actually immaterial. Bentham called it ‘a new mode of obtaining power of mind over mind’ and while he focused on its use as a prison, he was also aware of the idea’s usefulness for schools, asylums and hospitals. Bentham got the original idea following a visit to Belarus to see his brother who was managing sites there and had used the idea of a circular building at the centre of an industrial compound to allow a small number of managers to oversee the activities of a large workforce. This is something of a precursor of the scientific management theories of Frederick Taylor that continue to influence the way we work and manage people.

Indeed the layout of the Panopticon from Bentham’s original work – reproduced below – bears more than a passing resemblance to a contemporary open plan office building. Indeed Bentham’s description of the benefits of the Panopticon is like a rallying call for the apparent benefits of the open plan.

Morals reformed—health preserved—industry invigorated—instruction diffused—public burthens lightened—Economy seated, as it were, upon a rock—the Gordian knot of the poor-law not cut, but untied—all by a simple idea in architecture!

The idea has an enduring appeal. Michel Foucault did most to reapply the thinking behind the panopticon to 20th Century command and control structures in his 1975 book Discipline and Punish, in which he wrote “the Panopticon is a marvelous machine which, whatever use one may wish to put it to, produces homogeneous effects of power”. Just as Bentham had drawn inspiration for his idea from a work setting, so Foucault suggested that the idea as applied to prisons was a reflection of how the outside world functioned. This thinking is explicit in one of the Panopticon’s most famous practical examples, the ‘Model Prison’ in Cuba pictured in the header.

Perhaps this ability to mimic the open plan’s all-seeing eye in virtual space will drive the uptake of flexible working, or it may be just another tool of observation along with the building itself. Either way, our enduring love affair with the Panopticon in all its guises shows we are yet to reject the principles of scientific management. The most obvious contemporary manifestation of scientific management and the Panopticon itself is the open plan office.

In fact, there are many reasons why organisations like open plan offices beyond a simple impulse to watch people. When it comes to making the business case for them however, firms prefer to talk about some more than others. So while they prefer to focus on the argument in terms of how openness can foster better lines of communication, collaboration, teamwork and team spirit, they talk rather less about the fact that the open plan is a lot cheaper than its alternatives and how they like it because it allows them to keep an eye on what people are doing.

In theory at least, a great deal more of this surveillance now happens electronically so the need for physical presence should be less pressing, but the residual desire to see with one’s own eyes what people are doing remains. This is the instinct that constrains the uptake of flexible working and also means that there is a hierarchical divide in who gets to decide where they work. Practically all UK employees now have an equal right to request flexible working. But some are clearly more equal than others. A 2013 survey of 2,000 UK office workers by OnePoll found that 59 percent of senior staff were granted flexible working privileges compared to just 26 percent of those working lower down in the organisation.

The legal sector gives a particularly good example of how this manifests itself in practice. A recent survey of 3,400 solicitors carried out by the Law Society of Scotland found an increasing number were making use of flexible working. The research shows that while the majority of respondents (77 percent) continue to work full time, two thirds are now allowed to work away from their main place of work. In marked contrast to other professions, around two thirds of respondents did not access emails and work files while away from the office. Amongst the other interesting results from the survey is the fact that men are significantly more likely to be allowed to work from home than women (69 percent compared to 56 percent respectively) or work remotely (66 percent males compared to 51 percent of women).

This discrepancy may be a structural issue according to the report given that female employees in the legal profession have a tendency to fall into the £15,000 to £45,000 salary range whereas male employees are more likely to earn between £65,000 and £150,000 because women are more likely to be employed as administrators, trainees, associates and so on while men are more likely to be partners or directors.

At the heart of these status distinctions, there is evidently a degree of trust involved in the way firms not only offer employees flexible working arrangements but also their fondness for the open plan. Managers like to observe staff, but in return staff react to observation. We all understand that people act differently when they think they are being observed and it’s a characteristic that has been applied in interesting ways down the ages. Anybody interested in exploring the complex issues around open plan should have a listen to this fantastic programme on the BBC hosted by Julian Treasure.

Image: Friman, via Wikimedia Commons