April 28, 2020

A brief history of workplace disruption

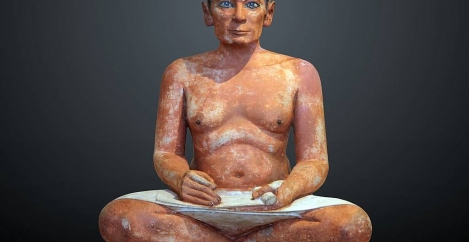

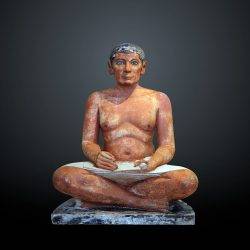

Office work has existed in some form ever since people started writing on tablets and papyrus. Depictions of clerical staff are common in the Bible and on the walls of pyramids. In the mid 14th Century the Church of San Nicolò, commissioned the artist Tomaso da Modena to create the fresco in the chapter room of the church depicting forty monks of the order hard at it at their desks. The word office itself derives from the famous Uffizi in Florence, created in 1560.

Office work has existed in some form ever since people started writing on tablets and papyrus. Depictions of clerical staff are common in the Bible and on the walls of pyramids. In the mid 14th Century the Church of San Nicolò, commissioned the artist Tomaso da Modena to create the fresco in the chapter room of the church depicting forty monks of the order hard at it at their desks. The word office itself derives from the famous Uffizi in Florence, created in 1560.

Things picked up after the Industrial Revolution, as is evident from the work of Charles Dickens amongst others. The first recognisable swivel chairs were developed by the likes of Thomas Jefferson, Albert Stoll and Peter Ten Eyck. These developments have tracked wider social, economic and cultural trends so the history of office furniture design holds a mirror to the world.

Early 20th Century

The first widely recognised example of a modern office is the 1904 Larkin Building designed by Frank Lloyd Wright. Shortly after Frederick Taylor introduces his theories of scientific management which applies industrial principles of the division of labour and time and motion to the office.

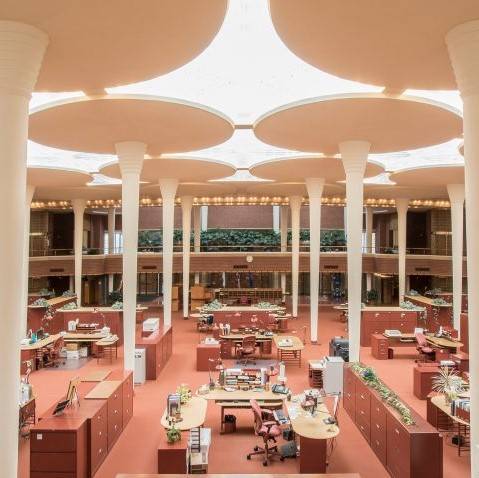

Soon, the likes of Steelcase and Herman Miller are founded to create products for the new forms of workplace. In 1939 Frank Lloyd Wright completed his work on the Johnson Wax building including The Great Workroom, an early form of open plan, and all the furniture within. Still truly breathtaking.

In the 1920s and later in Europe the development of new materials such as tubular steel combined with the rise of the Modernist movements and its figureheads such as Mies van der Rohe transformed the world of architecture and design.

In their wake and on the other side of the Atlantic, designers like Eero Saarinen and Charles and Ray Eames designed genuinely iconic products that endure to this day.

Mid 20th Century

While the Eames continued to create groundbreaking designs in a range of new materials, George Nelson introduced the first L-shaped workstation in 1947.

In Europe in the early 1950s a new conception of the open plan office was forming around the idea of Bürolandschaft. In contrast to the open plan bullpens that were now common in the US, the brothers Wolfgang and Eberhard Schnelle developed the idea based on a rejection of scientific management and a new focus on the needs of individuals and the flow of information between them. Although still open plan, it opened up a new idiom that still distinguishes European open offices from those in the US.

Also in Europe in the 1950s, Arne Jacobsen began to design his own generation of enduring furniture icons for Fritz Hansen. Many of the office furniture designs from this era continue to be widely specified and copied as they have achieved iconic status and serve as easily recognisable design signifiers.

1960s and 70s

The defining furniture system of the 1960s was Action Office by Herman Miller. Originally launched in 1964, it was updated in 1968 but this time supported by a Manifesto written by its designer Robert Propst which was just as influential as the furniture itself. Many of the statements about the design of spaces for people are just as relevant 50 years on, even if the furniture now looks anachronistic. It was to form the blueprint for American panel systems for the next few years.

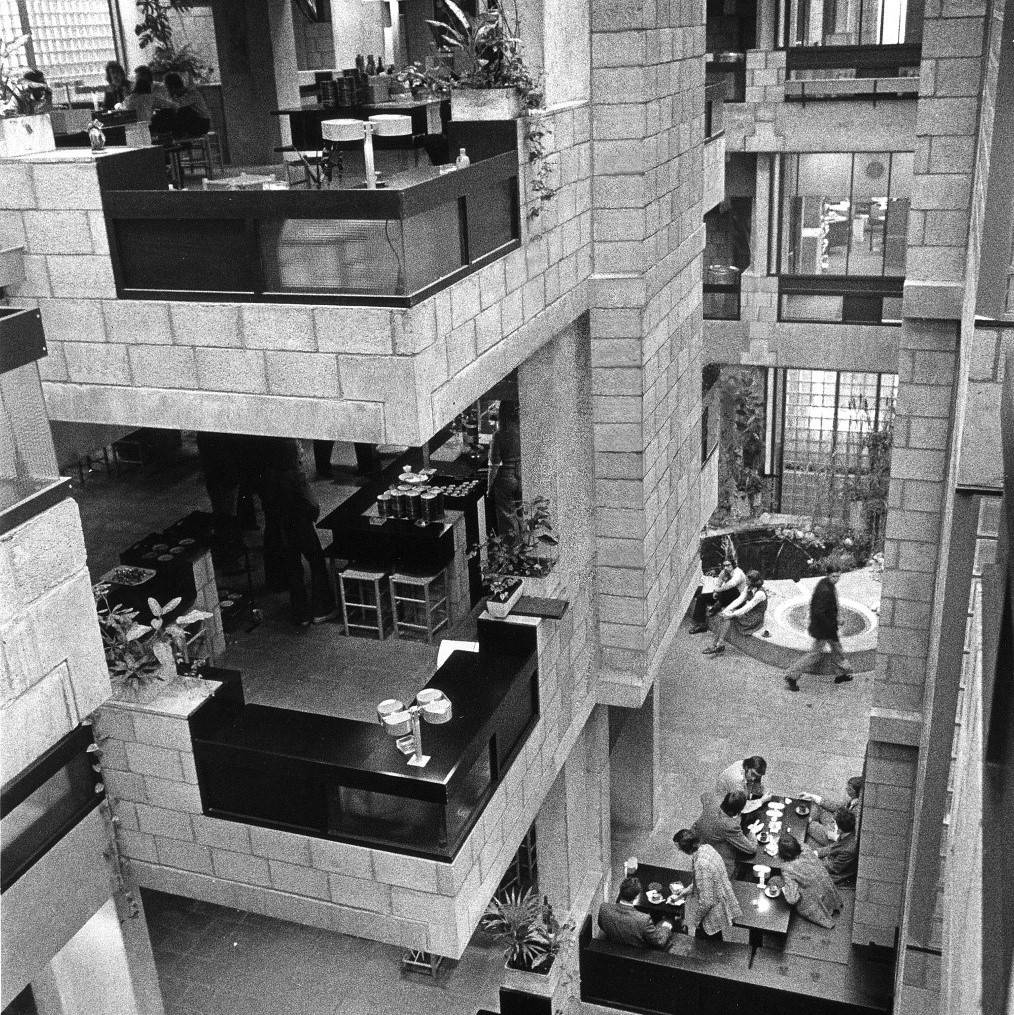

Meanwhile in Europe Herman Hertzberger’s designs for the Central Beheer building herald the idea that even a fixed form such as a building can have inbuilt adaptability to cope with changing technology and working cultures. It’s brutal aesthetic may have dated but its thinking remains current.

1980s

Computers with their large CPUs and CRT monitors start to appear on workstations and in response the desks become bigger and more heavily engineered. Cable management become a major issue and in response Douglas Ball designs the Race system for Sunar and Steelcase introduce their context core unit.

Europe follows suit with a range of solutions including sliding tops. As much attention is paid to the structure of the desks as their surfaces. A similar revolution is taking place with office seating as mechanisms become more complex and five star bases adopted as the norm in response to growing interest in ergonomics for computer users.

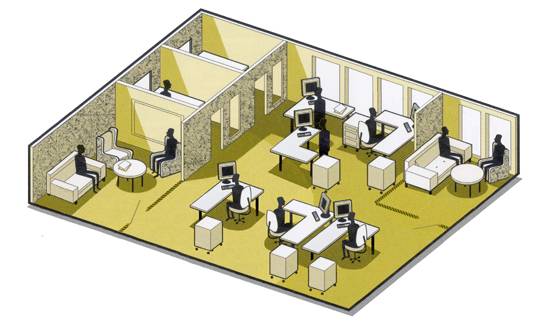

The idea of the combi-office, in which people choose between an open plan workstation and an unassigned personal office is an early progenitor of activity-based working. People start using terms like hot-desking.

1990s

The miniaturisation of technology and the Internet change everything. There is a great deal of talk about new ways of working but they remain more talked about than implemented.

The use of laptops and mobile phones begins to drive a reduction in the size of workstation footprints and desks. In the UK, the most talked about building is BA’s new Waterside building which had at its heart a ‘Street’ with cafes, shops, trees, plazas and road signage. It is an early example of both activity-based working and the idea that workplaces can function like communities or even cities.

Chiat Day’s vivid and playful New York offices from 1994 designed by Gaetano Pesce becomes the progenitor of creative offices with quirky features. In London a firm called Michaelides and Bednash working around a single shared long table that clearly announced the arrival of the bench desk that was to become the de facto default desk solution in the years that followed.

1994 proves a watershed in office furniture design with the introduction of the Aeron chair, Vitra’s Ad Hoc designed by Antonio Citterio and a product too ahead of its time called Kyo from President. All point to the world that was to arrive very soon after their launch.

The 21st century

In many ways the crystallisation of ideas that had formed at the end of the 20th Century. Work had become uncoupled in both space and time and as a consequence we saw a convergence not only of the places we work, and their design idioms, but an almost inability to distinguish between work time and the other facets of our lives.

Perhaps unsurprisingly wellbeing became as big a concern for firms as productivity, as did the war for talent. A greater focus on empowering people was one of the consequences.

A new way of occupying property also became evident with the growth of coworking as an alternative to traditional property models. Although in essence a development of serviced offices, the coworking phenomenon tapped into a perfect storm of change in the way people worked, globalisation, excessive rents in tech hot spots, organisations still smarting from the 2008 downturn and technological developments that facilitated new models of space.

In design terms, the century started with a clear focus on bench desks in open plan offices, often supported by break out spaces, meeting and team spaces and has evolved into something more sophisticated and adaptable – activity-based working.

Main image: The Seated Scribe, a sculpture dating back over 4,000 years now in The Louvre

This piece is taken from Indistinguishable from magic: What we need to understand about disruption and what it means for the workplace and appears in Issue 1 of IN Magazine

Anthony Brown is Chief Marketing Officer at BW@Workplace Experts