Many recent discussions have centered on the drawbacks of the open-plan office, a major format in the UK, and possible pathways to the communal workplace of the future. As part of this, it has been acknowledged that the factors responsible for determining the open-plan office’s performance are complex, and a number of the present-day workplace’s characteristics are messy and hard to quantify. In this brief article, I present anthropological methods as means for practitioners to further unpack the symbolic aspects of communication in open-plan offices and spark workplace solidarity.

Many recent discussions have centered on the drawbacks of the open-plan office, a major format in the UK, and possible pathways to the communal workplace of the future. As part of this, it has been acknowledged that the factors responsible for determining the open-plan office’s performance are complex, and a number of the present-day workplace’s characteristics are messy and hard to quantify. In this brief article, I present anthropological methods as means for practitioners to further unpack the symbolic aspects of communication in open-plan offices and spark workplace solidarity.

The open-plan office: working within view

The open-plan office is prevalent in the UK, where approximately 49 percent of employees are based in such settings. Globally, according to the same study, 23 percent are based in open-plan offices. Angela Love traces this high rate of adoption to the format’s 1960s emergence as the “’office of the future’” that, in contrast to the separated cubicles of yore, would provide increased transparency and accountability across all levels of management. For many firms, this heightened level of visibility leads to the frequently-stated benefit that adopting an open-plan model fosters collaboration and creativity, as the majority of staff work within view of each other.

[perfectpullquote align=”right” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]Among employees, there is a heightened awareness of being watched while at the workplace[/perfectpullquote]

What this suggests is that a greater degree of monitoring comes with this enhanced accessibility, as the employees’ actions are subject to the supervisor’s gaze. Among employees, there is a heightened awareness of being watched while at the workplace, and, consequently, rather than being passive subjects, staff members react to oversight. Dr. Alison Hirst and Dr. Christina Schwabenland find in a recent study that, within this hyper-observant environment, women are often disproportionately affected by perceptions of being under a watchful eye, and, in response, behaviors such as dress and other practices are often altered in order to create more favorable impressions.

Consequently, symbolic images abound in the workplace, an observation underlined by arguments that office designs “embody” organizational visions, and leadership roles continue to be displayed within teams despite the absence of more physical forms of authority like large, private offices. With the growth in distributed, agile working arrangements that result in employees often laboring elsewhere, it is becoming recognized that central offices are being restructured as centers for collaboration between co-workers and the overall employee experience. For “organizational solidarity” to be successfully cultivated, as called for in the “Working Beyond Walls” report (2008), it is thus necessary to understand how collaboration happens, and, henceforth, it is important to delve into the subtle images circulating in the workplace.

Anthropology and the workplace

The methods associated with anthropology and similar social science disciplines may be quite useful for practitioners seeking to explore aspects of communication in the workplace and foster organizational solidarity. According to the Royal Anthropological Institute, anthropology is a discipline that seeks to study humankind in and across diverse contexts.

In anthropology, much attention has been paid to the theme of symbolic communication within social spaces. Influenced by sociologist Erving Goffman, Michael Herzfeld (1985) examines how people behave within view of others, conceptualizing these actions as purposeful performances that aim to communicate meaning and convince audiences. Similarly, Michael Carrithers (2009) delves into the ways that people communicate by bringing attention to the routine rhetoric used in everyday inter-personal dialogues as a persuasive device. Culture, although a highly debated concept, is viewed by Carrithers as a shared conceptual toolbox for interpretation and action.

Importantly for our discussion, both anthropologists illustrate that such performances and uses of rhetorical devices are effective by drawing upon understood cultural concepts and images. They do so through utilizing classic methods associated with anthropology: observations of and conversations with people in the contexts they inhabit during their daily lives. Through these qualitative means (often referred to in the discipline as “ethnography”), they bring to light rich details intertwined within social interactions actions and use the insight provided by their informants to expose and explain underlying symbols present in communication.

[perfectpullquote align=”right” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]While quantitative techniques have definite applications, a sole focus on numbers and “big data” leaves out subtler aspects of workplace communication[/perfectpullquote]

Although practitioners of workplace strategy frequently utilize observations and stakeholder interviews, is has been noted recently that these methods have limited effectiveness when used due to taking too much time and generating too little comparative data. Yet, while quantitative techniques have definite applications, a sole focus on numbers and “big data” leaves out subtler aspects of workplace communication.

An anthropological approach harnesses the opportunities offered by office observations and interviews to note down and examine interactions between staff members that take place in and around the workplace. Paying attention to these details allows the symbols and images deployed in the open-plan office through communication by employees to be uncovered and explored, enabling practitioners to gain insight into how people collaborate with each other and experience the workplace. Hence, anthropology allows practitioners to plunge into the complexities of workplace culture and seek answers to messy questions.

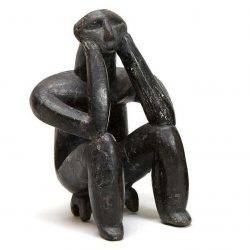

Image: A fired clay sculpture found in a grave at the Hamangia necropolis of Cernavod in Romania, dating back 7,000 years. Dubbed ‘The Thinker’, it is now an exhibit at the National History Museum in Bucharest

December 18, 2019

Anthropology might hold answers to the most difficult workplace challenges

by Christopher Diming • Comment, Workplace design

The open-plan office: working within view

The open-plan office is prevalent in the UK, where approximately 49 percent of employees are based in such settings. Globally, according to the same study, 23 percent are based in open-plan offices. Angela Love traces this high rate of adoption to the format’s 1960s emergence as the “’office of the future’” that, in contrast to the separated cubicles of yore, would provide increased transparency and accountability across all levels of management. For many firms, this heightened level of visibility leads to the frequently-stated benefit that adopting an open-plan model fosters collaboration and creativity, as the majority of staff work within view of each other.

[perfectpullquote align=”right” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]Among employees, there is a heightened awareness of being watched while at the workplace[/perfectpullquote]

What this suggests is that a greater degree of monitoring comes with this enhanced accessibility, as the employees’ actions are subject to the supervisor’s gaze. Among employees, there is a heightened awareness of being watched while at the workplace, and, consequently, rather than being passive subjects, staff members react to oversight. Dr. Alison Hirst and Dr. Christina Schwabenland find in a recent study that, within this hyper-observant environment, women are often disproportionately affected by perceptions of being under a watchful eye, and, in response, behaviors such as dress and other practices are often altered in order to create more favorable impressions.

Consequently, symbolic images abound in the workplace, an observation underlined by arguments that office designs “embody” organizational visions, and leadership roles continue to be displayed within teams despite the absence of more physical forms of authority like large, private offices. With the growth in distributed, agile working arrangements that result in employees often laboring elsewhere, it is becoming recognized that central offices are being restructured as centers for collaboration between co-workers and the overall employee experience. For “organizational solidarity” to be successfully cultivated, as called for in the “Working Beyond Walls” report (2008), it is thus necessary to understand how collaboration happens, and, henceforth, it is important to delve into the subtle images circulating in the workplace.

Anthropology and the workplace

The methods associated with anthropology and similar social science disciplines may be quite useful for practitioners seeking to explore aspects of communication in the workplace and foster organizational solidarity. According to the Royal Anthropological Institute, anthropology is a discipline that seeks to study humankind in and across diverse contexts.

In anthropology, much attention has been paid to the theme of symbolic communication within social spaces. Influenced by sociologist Erving Goffman, Michael Herzfeld (1985) examines how people behave within view of others, conceptualizing these actions as purposeful performances that aim to communicate meaning and convince audiences. Similarly, Michael Carrithers (2009) delves into the ways that people communicate by bringing attention to the routine rhetoric used in everyday inter-personal dialogues as a persuasive device. Culture, although a highly debated concept, is viewed by Carrithers as a shared conceptual toolbox for interpretation and action.

Importantly for our discussion, both anthropologists illustrate that such performances and uses of rhetorical devices are effective by drawing upon understood cultural concepts and images. They do so through utilizing classic methods associated with anthropology: observations of and conversations with people in the contexts they inhabit during their daily lives. Through these qualitative means (often referred to in the discipline as “ethnography”), they bring to light rich details intertwined within social interactions actions and use the insight provided by their informants to expose and explain underlying symbols present in communication.

[perfectpullquote align=”right” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]While quantitative techniques have definite applications, a sole focus on numbers and “big data” leaves out subtler aspects of workplace communication[/perfectpullquote]

Although practitioners of workplace strategy frequently utilize observations and stakeholder interviews, is has been noted recently that these methods have limited effectiveness when used due to taking too much time and generating too little comparative data. Yet, while quantitative techniques have definite applications, a sole focus on numbers and “big data” leaves out subtler aspects of workplace communication.

An anthropological approach harnesses the opportunities offered by office observations and interviews to note down and examine interactions between staff members that take place in and around the workplace. Paying attention to these details allows the symbols and images deployed in the open-plan office through communication by employees to be uncovered and explored, enabling practitioners to gain insight into how people collaborate with each other and experience the workplace. Hence, anthropology allows practitioners to plunge into the complexities of workplace culture and seek answers to messy questions.

Image: A fired clay sculpture found in a grave at the Hamangia necropolis of Cernavod in Romania, dating back 7,000 years. Dubbed ‘The Thinker’, it is now an exhibit at the National History Museum in Bucharest

Dr Christopher Diming is an Applied Social Scientist, Urban Anthropologist and Design Researcher