March 27, 2023

The five ages of the office and the man who shaped the way we talk about them

The office has passed through five ages. The ‘coffee houses’ of the 17th century, yielded to the ‘clerical factories’ of the 19th as machines revolutionised work. After the Second World War, the ‘corporate offices’ of global corporations and William Whyte’s Organization Man dominated the scene. Following the launch of IBM’s PC in the early-1980s, we saw the rise of ‘digital offices’ in the 1990s, complete with internet, email and social media. And for the past few years we have been moving inexorably towards the latest age: ‘network offices’. Each age was shorter than its predecessor: both the digital and network ages began less than a career span ago.

The office has passed through five ages. The ‘coffee houses’ of the 17th century, yielded to the ‘clerical factories’ of the 19th as machines revolutionised work. After the Second World War, the ‘corporate offices’ of global corporations and William Whyte’s Organization Man dominated the scene. Following the launch of IBM’s PC in the early-1980s, we saw the rise of ‘digital offices’ in the 1990s, complete with internet, email and social media. And for the past few years we have been moving inexorably towards the latest age: ‘network offices’. Each age was shorter than its predecessor: both the digital and network ages began less than a career span ago.

Listening to the cacophony on social media regarding the impact of Covid on the workplace, you might think that we are in an entirely novel phase of change. So much commentary is acontextual, has no empirical underpinning and revolves around what people want or wish would happen. But we are not in either ‘unprecedented’ or ‘unforeseen’ times.

Since the 1980s, one of the most insightful and articulate observers of the evolution of the office has been Dr Francis (Frank) Duffy, a founding partner of Duffy Ely Giffone & Worthington (DEGW). Frank, along with John Worthington and Peter Ely, all studied at the AA and then in the USA, and established a London practice for New York space planners JFN in the 1970s.

DEGW specialised in the design of office environments, but was distinctive for its focus on the relationships between design and its impact on the organisations that occupied them. After four decades of speculative development, where the overriding concern was to minimise development costs, this was a genuinely fresh approach.

I was lucky and privileged to work with Frank and colleagues in two capacities: first as a member of the DEGW team in the 1980s, and then as a client of DEGW in the 1990s, while managing research activities at developer Stanhope Properties. When I joined DEGW in 1984, the firm had just formed its defining relationship with Stanhope founder Sir Stuart Lipton, a partnership that was to produce some of the most revolutionary thinking on the nature of the office, leading to a re-invention of the product. It was the most exhilarating of times: research is often caricatured as a backward looking activity. But there we were, reinventing the past to change the future.

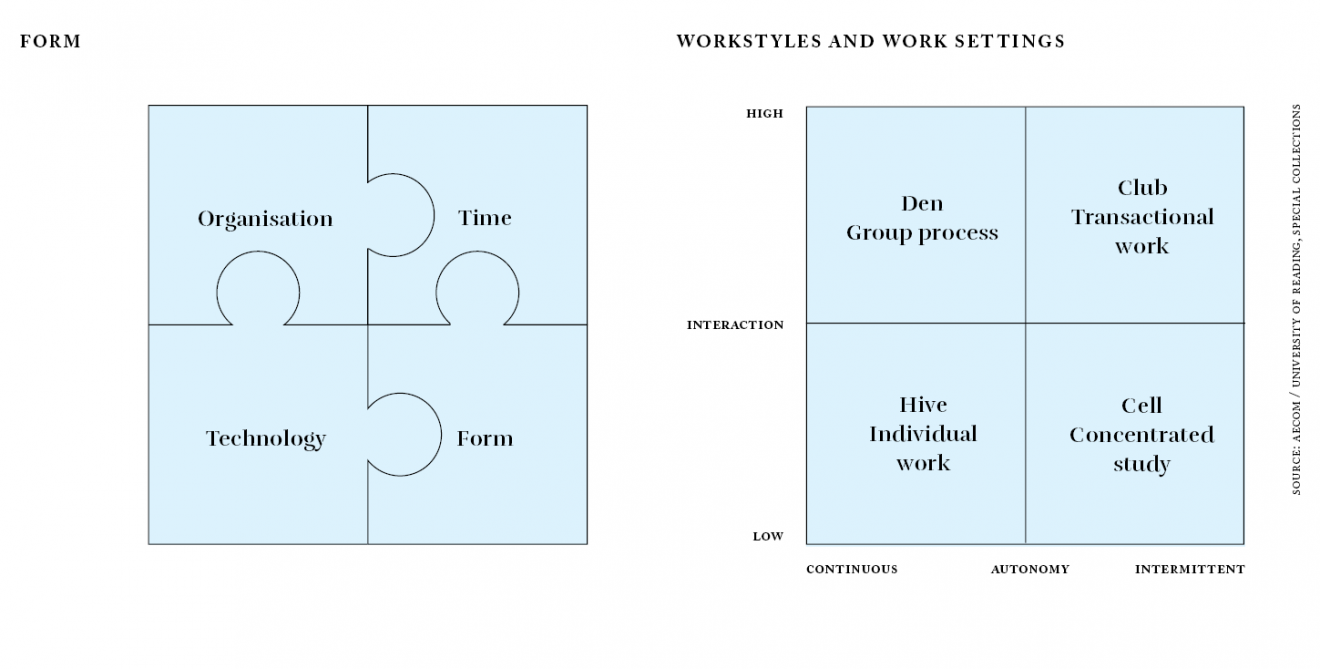

In this period of creativity and beyond, Frank and the men and women he worked with, produced a large and original body of applied work. Through it all, four themes can be detected which, together and in combination, form a timeless construct for analysing the office that we would be wise to heed today.

Time: Frank was fascinated by the life cycle of buildings, particularly the tension between the time horizons of investors (long) and those of occupiers (short). This interest expressed itself in the 1976 masterpiece, Planning Office Space which described four distinct building elements. The shell is the basic structure and cladding (with a lifespan of 70+ years); services include heating, ventilation, lighting, power (c15 years); scenery includes ceilings and partitions (5-10 years); and settings include the furnishings and equipment (day-to-day).

In combination, these building features can evolve over time, allowing buildings to adapt to new uses and occupiers: “a whole series of layers of materials with varying degrees of longevity”. This crucial insight suggested that each element should be designed inter-dependently, to allow replacement and upgrade at different stages of the building life cycle. Never has this message been more important than today when we consider zero carbon growth, and the balance that must be struck between new build and re-use.

Form: DEGW ‘invented’ building appraisal, the technique of comparing the physical characteristics of buildings in a consistent and objective manner, and matching them with occupier profiles. The earliest work, in 1984, was Four Properties Compared, undertaken for the Finsbury Avenue project in the City of London. This was followed in 1986 by an altogether more ambitious project and perhaps the most influential report of the genre: Eleven Contemporary Office Buildings: A Comparative Study. The report compared the first two Broadgate buildings with nine others in the City.

Building appraisal is a technique that tests whether the spatial needs of a particular occupier, or an occupier type, could be met by an actual building, or a design for one. The style and format of Eleven Buildings were simple to use and visually pleasing. The report itself made very clear:

“The purpose of this comparison … is to remedy the damaging lack of information about building performance. The data presented here are not about how buildings are constructed but what they can do – [and] what capacity they have to accommodate the new kinds of City organisations.”

Technology: Frank understood the role of technology in the workplace as an agent of change.

He co-wrote some of the very first research exploring the potential impact of organisational change and emerging technologies on buildings. Organisations, Buildings and Information Technology (ORBIT) was the result of a multi-client study, carried out in 1982 by DEGW with Building Use Studies and EOSYS.

Frank also saw early the relationship between technology and ways of working. As he wrote in The New Office:

“Ways of working are changing radically. Information technology is seeing to that. Based on very new and very different assumptions about the use of time and space, new ways of working are emerging fast. They are inherently more interactive than old office routines and give people far more control over the timing, the content, the tools and the place of work.”

He wrote of the “possibilities inherent in information technology to allow staff to enjoy a new freedom in relating home, work, and leisure”.

Organisation Finally, Frank had a fundamental understanding of organisations and their relationship with space. First, he understood that organisations themselves were subject to a rapidly changing economy.

There was – and is – a need to find dynamic new ways to accommodate ever-changing organisations that continually have to respond to an increasingly unstable and unpredictable business environment.

And then he was fascinated by the relationship between the individual and the corporation, and the constant negotiation between the two, and how this expressed itself in the nature of space.

Inadequate buildings

In 1984 and 1985, DEGW ran a series of focus groups involving individuals from City companies. The focus groups revealed a deep-seated feeling among the participants that the buildings they occupied were inadequate to meet their operational needs in a rapidly changing business environment. The results of the work were summarised in Accommodating the Changing City.

Frank’s insight was that organisations were coming to be managed less as huge corporate machines and more as systems or networks in which work was increasingly about short-term assignments, communication, mobility and connectivity.

In such organisations, knowledge becomes the primary currency of exchange, and traditional approaches to command and control structures break down. He explored the need for ‘interaction’ and ‘autonomy’ in work to describe the need for four generic types of work setting.

The evolving understanding of time, form, technology and organisation over the past three decades or so has transformed office real estate. There now exists real estate research, when none existed; the same goes for real estate management and workplace strategy as professions. Real estate as a commodity via flex space and the emergence of a focus on ‘workplace experience’ have changed product and offer fundamentally. There are countless advances.

Those who argue that the office has not changed over recent decades; that pre-pandemic workstyles are the ‘bad old ways’; that most offices are inhuman, oppressive, insufferable, over-bearing, unhealthy, unattractive and unfit for purpose, and who believe that all landlords are unthinking, ‘dinosaurs’, fail to grasp the contextual significance of the issues with which we grapple today.

Nearly 45 years ago Frank and colleagues wrote that, despite the success of ‘corporatism’, as measured in its own terms, the work environment had failed to modernise.

Older architectural magazines reveal with cruel clarity the prevailing standard of office design in the late 50s and early 60s. Advertisements display more vividly than editorial what seems to us now an astonishingly uncomfortable physical environment – hard floor finishes, lots of glazed partitioning, surface mounted light fittings, bulky steel desks….

They were right. But due to their contribution and that of countless others since, the same criticism could not be levelled today.

We’ve come a long way, but the journey continues. As we emerge from the short-term responses to the Covid-19 crisis, and as workstyles adapt to a much more widely-accepted form of agile working, it is clear that ‘the office’ must continue to adapt to new circumstances.

In Work and the City, Frank argued that in the networked office age, reconfigured space and radical approaches to working and living spaces needed to be supported by the “introduction of a user-based and responsible, demand-led system of procurement and delivery”.

He was also very critical of the ‘iron fist’ of the supply side’. And herein lies the real nub of the task that lies ahead of us.

The office as a built form has, and will continue, to evolve. The fundamental, unresolved issue, is how we evolve from a supply-led to a demand-led ‘industry’. The shift from a capital-based to an income-based model is uncomfortable for many, but it is also inevitable.

The opportunity needs to be grasped with enthusiasm; the industry needs to re-skill and learn the hard lesson that real estate is a by-product, not an end in itself. For our customers, it is a commodity not an asset.

Making the transition to a demand-led, service-based industry will be another exhilarating experience.

Rob Harris is principal of Ramidus Consulting. He has over 30 years experience within the property sector, specialising in research and workplace strategy. Prior to setting up Ramidus, Rob worked for Interior Services Group, Stanhope Properties, Hillier Parker (now CBRE), Debenham Tewson & Chinnocks (now DTZ) and DEGW.

Main image: The pioneering SAS headquarters in Stockholm designed by Niels Torp

This article first appeared in Issue 8 of IN Magazine