December 17, 2018

Meatspace, cyberspace, the uncertainty of expertise and some other stuff

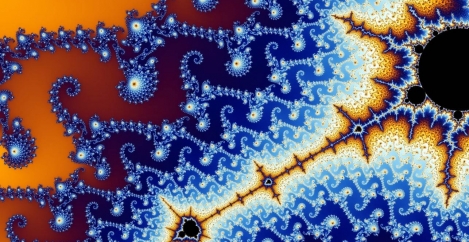

The sign that somebody knows their stuff about a subject is often that whatever they say about it is full of questions, equivocations and caveats. They’ll often start out by saying things are complicated in mitigation of their opinion on a particular topic. They’ll say there are no silver bullets. It’s almost always neophytes, chancers and the conflicted that offer certainty. To prove my point here is David D’Souza of the CIPD making a point about the tendency to look for pat, narrow solutions to complex, broad challenges. Not only does he have something interesting to say, you know that he has the depth and breadth of knowledge to expand on each of the points he makes with yet more sophistication. It’s fractal thinking.

The sign that somebody knows their stuff about a subject is often that whatever they say about it is full of questions, equivocations and caveats. They’ll often start out by saying things are complicated in mitigation of their opinion on a particular topic. They’ll say there are no silver bullets. It’s almost always neophytes, chancers and the conflicted that offer certainty. To prove my point here is David D’Souza of the CIPD making a point about the tendency to look for pat, narrow solutions to complex, broad challenges. Not only does he have something interesting to say, you know that he has the depth and breadth of knowledge to expand on each of the points he makes with yet more sophistication. It’s fractal thinking.

You can see this kind of thought too in this piece by Neil Usher, who has been ubiquitous over the last few months since the publication of his book The Elemental Workplace and his switch from a corporate workplace role to an advisory one. Neil is certain about many things, and has the insight and experience to back them up, but also knows enough to realise how little he knows.

“We still love a shiny yet empty and meaningless soundbite, or a sensational stat from a jamboree bag research kit. We love it more when we don’t have to work too hard to find it. A lot of the bloggers I once loved to read have stopped, and we’re much poorer for it. The more that Workplace attracts attention the more the bell-curve inevitably bulges with mediocrity. Accept nothing at face value until you’ve thought it through. You’re not an influencer unless you’re sharing something useful, so avoid the rising torrent of click-bait and don’t pass anything on until you’ve read it and see it of value in a discernible way. Share less, but better. That way we’ll all learn together.”

James Woudhuysen shares a similarly sceptical approach to easy answers, albeit from a more contrarian perspective. This is a piece he wrote appropriately enough for the Leesman Review, published by an organisation dedicated to creating credible evidence for workplace decision makers.

Of course, facts aren’t everything and logic doesn’t always lead to answers. This will be the central conundrum we face as we learn to live with AI, a point raised in this piece about the logician Kurt Gödel which concludes that we shouldn’t muddle truth with provability because, as humans, we are more interesting than that. We don’t really know what intelligence and consciousness are, and yet we’re talking about them as if we do while we’re designing machines to ape them.

The unknowability of it all

This is why so many pieces about AI have such a philosophical aspect. We are already having new conversations about what it means to be human, as in this piece from Pew, and also about how that is changing, for example in this piece on how tech use is rewiring our brains from an early age. The unknowability of this overlap between meatspace and cyberspace and its relevance for every aspect of our lives and the world in which we live is developed in this piece from Nature magazine.

One other problem about facts is that they can obscure facets. So, the story of AI is often told in big numbers, especially a comparison of the number of jobs that will be lost compared to the numbers gained. The picture this creates is of a generalised shift across the workforce from one type of work to another, and sometimes to no work at all. What this ignores is that these are averages and generalisations and don’t look at how such changes will affect individuals, regions and demographics in different ways. This piece from McKinsey illustrates the point with regard to the impact on black Americans who are more likely to be in the sorts of jobs that will bear the first brunt of automation and may not have the skills and opportunities that would allow them to respond.

Ignoring the lumpy implications of job automation is something worth bearing in mind when you see one of those pieces arguing we should move to a four day week or six hour day, or just working less generally. These are changes that might be a proactive choice for certain people but need to be facilitated in the case of others who aren’t able to make those choices in the same way, if at all.

Finally, a story about ants nests to provide a handy metaphor for how organisational culture and individual thought processes work. Sometimes there aren’t reasons for things, or at least none you can pin down with certainty. Just because we can observe it, doesn’t mean it isn’t a mystery.