Ever since technology first made it possible for people to work remotely from their colleagues, there has been speculation not only that office design should change but even that the physical office could be dispensed with entirely, and with it the idea that people should come together to work in the same place at the same time to achieve common goals and to share in a common identity.

Ever since technology first made it possible for people to work remotely from their colleagues, there has been speculation not only that office design should change but even that the physical office could be dispensed with entirely, and with it the idea that people should come together to work in the same place at the same time to achieve common goals and to share in a common identity.

This is a perfect example of the tendency we all share of confusing what is possible with what will happen. This appears to be a particular issue when we consider the effects of new technology. Hence the enduring talk of the death of the office, which technology makes possible but which people make impossible.

The latest study to challenge the death of the office narrative shows that more than half (59 percent) of flexible workers feel their skills and knowledge are falling behind that of their colleagues, Two-thirds (65 per cent) of 1,700 part-time workers questioned for the Part-time work: The exclusion zone? report from Timewise said they felt isolated from their teams, particularly as it was harder for them to attend social events. Three in five (61 per cent) noted they felt less up-to-date because they missed meetings.

People are drawn to the idea of remote working, but the office exerts its own gravitation. One of the key areas of research that describes the tension between these two forces is found in the work of Tom Allen at MIT.

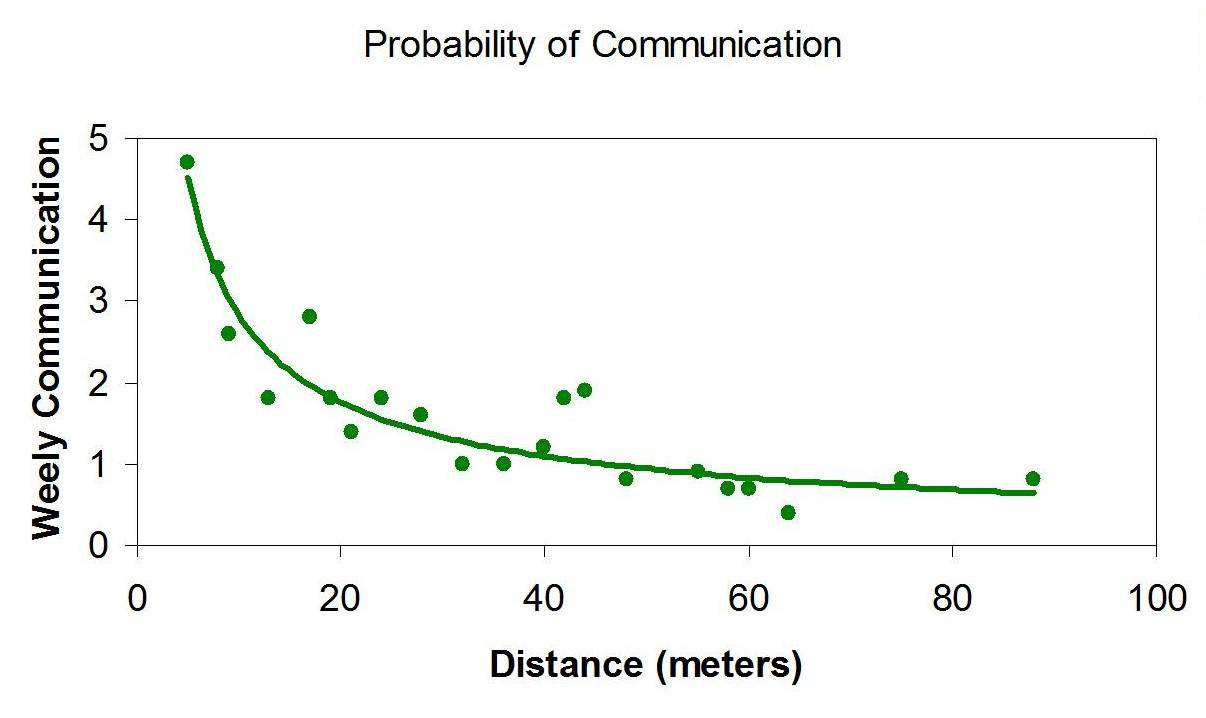

Allen made his name in 1984 with the publication of a book called Managing the Flow of Technology which first popularised the Allen Curve, a graph of his research findings which shows a powerful negative correlation between physical distance and the frequency of communication between colleagues. So precisely can this be defined, that Allen found that 50 metres marks a cut-off point for the regular exchange of certain types of technical information.

The book is based on research Allen and his colleagues carried out in the late 1970s with a group of engineers. They quickly determined that the distance between the engineers’ desks in an office design had a direct and significant impact on the frequency of communication between them. We don’t even need to be isolated to communicate less, just further apart.

The book is based on research Allen and his colleagues carried out in the late 1970s with a group of engineers. They quickly determined that the distance between the engineers’ desks in an office design had a direct and significant impact on the frequency of communication between them. We don’t even need to be isolated to communicate less, just further apart.

Of course, technology has changed the dynamics of this situation since the 1970s. It’s a point Allen himself addresses in his 2006 book The Organization and Architecture of Innovation co-authored with German architect Gunter Henn. The book explores how office design, physical space, social networks, flows of information and organisational structure must be integrated to drive innovation.

What it finds is that far from lessening in importance, the building is gaining a more prominent, if different role and that the physical distance between individuals is an essential element in the development of working relationships and the way ideas and information flow. Physical space is integral to innovation.

The book makes the following point based on its research: “Rather than finding that the probability of telephone communication increases with distances, as face to face probability decays, our data shows a decay in the use of all communication media with distance. We do not keep separate sets of people, some of which we communicate in one medium and some by another. The more often we see someone face to face, the more likely it is that we will telephone the person or communicate in some other medium.”

An issue of quality

[perfectpullquote align=”right” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]If design can foster more interactions between people in terms of both exposure and frequency, it’s not only more likely that they will share information, but also feel a closer bond[/perfectpullquote]

There is another aspect to this issue. While Allen’s work focuses on the quantity of information people exchange, our distance from other people also influences the quality of our relationship with them. A blurred distinction can be drawn between the idea of proximity and the more arcane idea of propinquity. The latter has more to say about the sense of kinship between people but both have important implications for office design.

The US undersecretary to both John F Kennedy and Lyndon B Johnson was a man called George Ball. He popularised an idea that became known as the Ball Rule of Power which can be summarised as ‘the more direct access you have to the president, the greater your power, no matter what your title actually is’.

Ball came to be associated with the phrase ‘nothing propinks like propinquity’ but he had stolen it from a Chapter Title in Ian Fleming’s novel Diamonds are Forever.

This theory was based on a study carried out by the psychologists Leon Festinger, Stanley Schachter and Kurt Back carried out on the apartments of the campus of MIT in Cambridge, Massachusetts in 1950. The researchers found that the students who lived on the same floor typically had closer friendships with each other than with those who lived on a different floor. Relationships were also affected by how close people lived to shared spaces such as stairwells and entrances.

This human characteristic, seemingly undimmed by our exposure to modern technology, has enormous implications for the way we design our surroundings, including our workplaces. If design can foster more interactions between people in terms of both exposure and frequency, it’s not only more likely that they will share information, but also feel a closer bond.

It might also explain why there is so much more interest in agile working environments. While the traditional open plan office is focussed primarily on proximity as a way of encouraging communication, the agile workplace aims to encourage movement and more frequent interactions between people. It also allows people to define their day by working near to the people they need or prefer to work with.

Main Image: KI

Jonathan Hindle is Group Managing Director at KI EMEA and Chair of the British Furniture Confederation.

July 23, 2019

Office design should take account of the quality of interactions as well as quantity

by Jonathan Hindle • Comment, Workplace design

This is a perfect example of the tendency we all share of confusing what is possible with what will happen. This appears to be a particular issue when we consider the effects of new technology. Hence the enduring talk of the death of the office, which technology makes possible but which people make impossible.

The latest study to challenge the death of the office narrative shows that more than half (59 percent) of flexible workers feel their skills and knowledge are falling behind that of their colleagues, Two-thirds (65 per cent) of 1,700 part-time workers questioned for the Part-time work: The exclusion zone? report from Timewise said they felt isolated from their teams, particularly as it was harder for them to attend social events. Three in five (61 per cent) noted they felt less up-to-date because they missed meetings.

People are drawn to the idea of remote working, but the office exerts its own gravitation. One of the key areas of research that describes the tension between these two forces is found in the work of Tom Allen at MIT.

Allen made his name in 1984 with the publication of a book called Managing the Flow of Technology which first popularised the Allen Curve, a graph of his research findings which shows a powerful negative correlation between physical distance and the frequency of communication between colleagues. So precisely can this be defined, that Allen found that 50 metres marks a cut-off point for the regular exchange of certain types of technical information.

Of course, technology has changed the dynamics of this situation since the 1970s. It’s a point Allen himself addresses in his 2006 book The Organization and Architecture of Innovation co-authored with German architect Gunter Henn. The book explores how office design, physical space, social networks, flows of information and organisational structure must be integrated to drive innovation.

What it finds is that far from lessening in importance, the building is gaining a more prominent, if different role and that the physical distance between individuals is an essential element in the development of working relationships and the way ideas and information flow. Physical space is integral to innovation.

The book makes the following point based on its research: “Rather than finding that the probability of telephone communication increases with distances, as face to face probability decays, our data shows a decay in the use of all communication media with distance. We do not keep separate sets of people, some of which we communicate in one medium and some by another. The more often we see someone face to face, the more likely it is that we will telephone the person or communicate in some other medium.”

An issue of quality

[perfectpullquote align=”right” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]If design can foster more interactions between people in terms of both exposure and frequency, it’s not only more likely that they will share information, but also feel a closer bond[/perfectpullquote]

There is another aspect to this issue. While Allen’s work focuses on the quantity of information people exchange, our distance from other people also influences the quality of our relationship with them. A blurred distinction can be drawn between the idea of proximity and the more arcane idea of propinquity. The latter has more to say about the sense of kinship between people but both have important implications for office design.

The US undersecretary to both John F Kennedy and Lyndon B Johnson was a man called George Ball. He popularised an idea that became known as the Ball Rule of Power which can be summarised as ‘the more direct access you have to the president, the greater your power, no matter what your title actually is’.

Ball came to be associated with the phrase ‘nothing propinks like propinquity’ but he had stolen it from a Chapter Title in Ian Fleming’s novel Diamonds are Forever.

This theory was based on a study carried out by the psychologists Leon Festinger, Stanley Schachter and Kurt Back carried out on the apartments of the campus of MIT in Cambridge, Massachusetts in 1950. The researchers found that the students who lived on the same floor typically had closer friendships with each other than with those who lived on a different floor. Relationships were also affected by how close people lived to shared spaces such as stairwells and entrances.

This human characteristic, seemingly undimmed by our exposure to modern technology, has enormous implications for the way we design our surroundings, including our workplaces. If design can foster more interactions between people in terms of both exposure and frequency, it’s not only more likely that they will share information, but also feel a closer bond.

It might also explain why there is so much more interest in agile working environments. While the traditional open plan office is focussed primarily on proximity as a way of encouraging communication, the agile workplace aims to encourage movement and more frequent interactions between people. It also allows people to define their day by working near to the people they need or prefer to work with.

Main Image: KI

Jonathan Hindle is Group Managing Director at KI EMEA and Chair of the British Furniture Confederation.