In 2015, the American Psychological Association chose American Express as the inaugural winner of the Organizational Excellence Award, recognizing successful efforts to integrate psychology and prioritize behavioral health and emotional well-being in the workplace. American Express had an employee assistance program (EAP) for workers dealing with depression and other mental health challenges. The EAP was a telephone-consultation system and only about 4 percent of employees utilized it. After the firm added on-site counselors to meet with employees for free—and rebranded the EAP as part of its “Healthy Living” —the usage rate more than doubled.

In 2015, the American Psychological Association chose American Express as the inaugural winner of the Organizational Excellence Award, recognizing successful efforts to integrate psychology and prioritize behavioral health and emotional well-being in the workplace. American Express had an employee assistance program (EAP) for workers dealing with depression and other mental health challenges. The EAP was a telephone-consultation system and only about 4 percent of employees utilized it. After the firm added on-site counselors to meet with employees for free—and rebranded the EAP as part of its “Healthy Living” —the usage rate more than doubled.

At EY, the multinational professional services firm formerly known as Ernst & Young, employees are trained to recognize emotional changes in a colleague, and ask if they are feeling OK. The question is not meant to diagnose a mental illness or problematic substance use, but to express care and start the process of getting help. A video External link explaining the concept to employees recognizes that in a 12-member team, three people are likely struggling.

Both of these companies recognize the pervasiveness of depression and mental illness, and the importance of accommodating and supporting employees who are suffering. Programs such as these will become even more important for the next generation of workers who may feel less stigmatized about discussing and addressing mental health concerns in the workplace.

Both of these companies recognize the pervasiveness of depression and mental illness, and the importance of accommodating and supporting employees who are suffering. Programs such as these will become even more important for the next generation of workers who may feel less stigmatized about discussing and addressing mental health concerns in the workplace.

“I think that the younger folks today have a more holistic view of well-being and are more aware of the importance of work-life balance,” said Dr. Eric Beeson, a core faculty member at Counseling@Northwestern and a licensed professional counselor. “However, this work-life balance is often challenged with performance demands. Thankfully some organizations are fostering social and emotional health in the workplace, so if folks are going to sacrifice balance, some of those needs can be met in the office.”

According to a study of national trends on depression among adolescents and young adults published in the journal Pediatrics, the prevalence of having a major depressive episode in the past 12 months increased almost 37 percent for teens between 2011 and 2014. Between 13 percent and 20 percent of adolescents have a mental health condition in a given year, according to a report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Dr. Beeson noted that actual incidence of mental health disorders may not be higher for younger generations than their parents or grandparents. Rather, younger generations are likely more aware of mental health, live in a world with less stigma (although stigma is still a challenge), and are more likely to seek treatment, leading to increased rates cited.

At the same time, workplaces like American Express and EY that embrace mental health care are not the standard. Many employers are not actively meeting the mental health needs of their employees.

According to a 2017 poll for the American Psychological Association, just 48 percent of employed adults reported their employer provided resources to help meet mental health needs and even fewer, 42 percent, reported receiving sufficient resources from their employers to help manage stress.

Cheryl Squadrito remembers the cloud of depression hanging over her former workplace, a newspaper in New Jersey where she worked as a lifestyle reporter, and how it affected the work of nearly everyone in the newsroom. There were few windows and desks were crammed together, ostensibly to promote teamwork. People having a bad day seemed intent on making sure everyone else did, too. Squadrito said managers had no training about how to mitigate stress. She recalled an outburst as an editor screamed at a colleague and stormed out.

These previous negative experiences helped Squadrito shape how she addresses workplace stress when she launched her public relations firm in Philadelphia, Media Friendly PR. She said she tries to find the positive in every situation and encourages her employees to have fun in the office when they are off deadline. She recently used a work day to take her staff to a new movie.

“If someone is going through a problem, I ask them to just talk to me and let me know what’s going on,” Squadrito said. “I’m OK with giving extra time for work on projects . . . And the office is very happy because of it.”

Caring for employees’ mental health is not merely a nice thing to do—it can also save money.

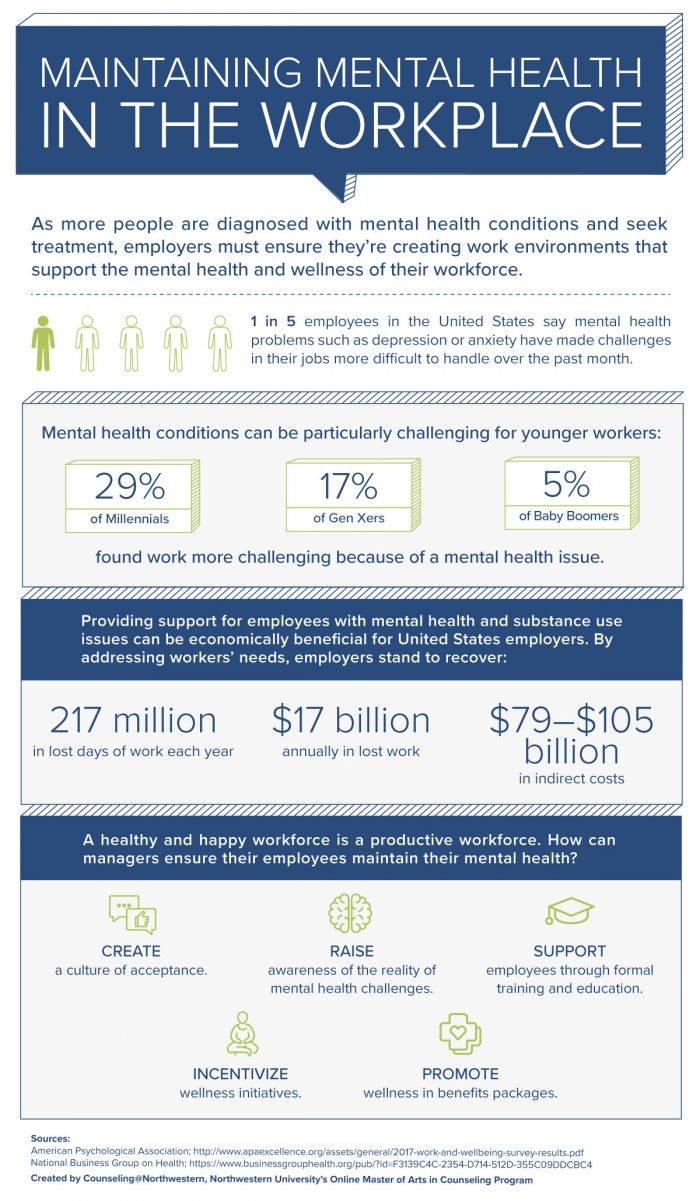

Mental illness is costly to employers. According to the National Business Group on Health, mental illness causes more days of work loss and work impairment than many other chronic conditions such as diabetes, asthma, and arthritis. Approximately 217 million days of work are lost annually due to productivity decline related to mental illness and substance-use disorders, costing U.S. employers $17 billion.

Mental Health America, a nonprofit dedicated to addressing the needs of those with mental illness and to promoting the mental health of all, says a depressed employee will often not seek treatment because they fear how it will affect their job and they are concerned about confidentiality.

“There’s sometimes the fear of repercussions,” said Dr. Beeson. “There’s a fear that people will be viewed as weaker or ‘less than,’ or depending upon the mental illness, maybe (having) a moral failing of their own.”

For example, in Los Angeles, a sales rep for a cable provider who suffered from a mental illness had to take a leave of absence from the job where he had worked for 24 years. When he was not ready to come back, the leave was extended, then extended again. Finally, he was fired for what the company called his “repeated, prolonged leaves of absence, which rendered him unable or unwilling to work.”

The employee sued, alleging his employers had allowed other sales reps to take more time off, including one who was out seven months, and another who was out 18 months. The employee had not previously had a negative performance review. The court sided with the employee, reasoning that under California’s Fair Employment and Housing Act, as long as a worker had a tentative return date, more time off could be a reasonable accommodation.

It can be difficult for an employee to win such a case, said Anthony D. Kuchulis, a lawyer with Barran Liebman in Portland, Ore., who represents employers and management in litigation. Still, he recommends employers stay out of such litigation, because while the employee will recover his or her attorney fees if successful on a stress disability claim, courts almost never let employers recover legal fees in cases they win.

“As a practical matter, I always recommend moving away from a risk management strategy based on strict legal analysis, and instead counsel companies to be generous and compassionate with employees reporting disabilities, even when the employee’s requests may exceed the company’s legal obligations to accommodate,” Kuchulis said.

Dr. Beeson said companies might consider employing a nurse, counselor, or psychologist on staff. “I think increasing access to services on-site is the exception, but probably one of the more effective models for employers to incorporate,” he said.

He agreed that a healthier workplace saves money. “The bottom line is important,” Dr. Beeson said. “I think performance goes up traditionally when people are healthier. It helps you accomplish your mission. It’s an investment in people’s lives as well as in the health of your business.”

It’s the law

There is another good reason for companies to accommodate people with mental illness: it is illegal not to, in the US and elsewhere.

An employer can’t discriminate against an employee who has a mental health condition. This includes firing someone, rejecting them for a job or promotion, or forcing them to take leave.

That doesn’t mean an employer has to hire or keep people in jobs they can’t perform or employ people who pose a significant risk of substantial harm to self or others.

But an employer cannot rely on myths or stereotypes about a mental health condition when deciding whether someone can perform a job or whether they pose a safety risk. To reject someone based on a mental health condition, the employer must have objective evidence that the person can’t perform their job duties, or that they would create a significant safety risk, even with a reasonable accommodation.

Squadrito said employees who recognize they have depression are far from a liability—they can be an asset. That type of introspection lends itself to greater creativity, a tremendous commodity to a public relations firm.

“Being self-aware also brings out the creativity in people,” she said. “[The presence of a mental illness] doesn’t hinder me from hiring anybody.”

Five tips for employers

A healthy and happy workforce is a productive workforce. How can managers ensure their employees maintain their mental health? Dr. Beeson offers five simple tips that can employers can implement:

- Create a culture of acceptance.

- Raise awareness about the reality of mental health challenges.

- Support employees through formal training and education.

- Incentivize wellness initiatives.

- Promote wellness in benefits packages.

_________________________________________

Colleen O’Day is a Marketing Manager and supports community outreach for 2U Inc.’s social work, mental health, and K-12 Education programs. Find her on Twitter @ColleenMODay.

Colleen O’Day is a Marketing Manager and supports community outreach for 2U Inc.’s social work, mental health, and K-12 Education programs. Find her on Twitter @ColleenMODay.

June 13, 2018

US companies are waking up to the benefits of caring for employee mental health

by Colleen O'Day • Comment, Wellbeing

At EY, the multinational professional services firm formerly known as Ernst & Young, employees are trained to recognize emotional changes in a colleague, and ask if they are feeling OK. The question is not meant to diagnose a mental illness or problematic substance use, but to express care and start the process of getting help. A video External link explaining the concept to employees recognizes that in a 12-member team, three people are likely struggling.

“I think that the younger folks today have a more holistic view of well-being and are more aware of the importance of work-life balance,” said Dr. Eric Beeson, a core faculty member at Counseling@Northwestern and a licensed professional counselor. “However, this work-life balance is often challenged with performance demands. Thankfully some organizations are fostering social and emotional health in the workplace, so if folks are going to sacrifice balance, some of those needs can be met in the office.”

According to a study of national trends on depression among adolescents and young adults published in the journal Pediatrics, the prevalence of having a major depressive episode in the past 12 months increased almost 37 percent for teens between 2011 and 2014. Between 13 percent and 20 percent of adolescents have a mental health condition in a given year, according to a report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Dr. Beeson noted that actual incidence of mental health disorders may not be higher for younger generations than their parents or grandparents. Rather, younger generations are likely more aware of mental health, live in a world with less stigma (although stigma is still a challenge), and are more likely to seek treatment, leading to increased rates cited.

At the same time, workplaces like American Express and EY that embrace mental health care are not the standard. Many employers are not actively meeting the mental health needs of their employees.

According to a 2017 poll for the American Psychological Association, just 48 percent of employed adults reported their employer provided resources to help meet mental health needs and even fewer, 42 percent, reported receiving sufficient resources from their employers to help manage stress.

Cheryl Squadrito remembers the cloud of depression hanging over her former workplace, a newspaper in New Jersey where she worked as a lifestyle reporter, and how it affected the work of nearly everyone in the newsroom. There were few windows and desks were crammed together, ostensibly to promote teamwork. People having a bad day seemed intent on making sure everyone else did, too. Squadrito said managers had no training about how to mitigate stress. She recalled an outburst as an editor screamed at a colleague and stormed out.

These previous negative experiences helped Squadrito shape how she addresses workplace stress when she launched her public relations firm in Philadelphia, Media Friendly PR. She said she tries to find the positive in every situation and encourages her employees to have fun in the office when they are off deadline. She recently used a work day to take her staff to a new movie.

“If someone is going through a problem, I ask them to just talk to me and let me know what’s going on,” Squadrito said. “I’m OK with giving extra time for work on projects . . . And the office is very happy because of it.”

Caring for employees’ mental health is not merely a nice thing to do—it can also save money.

Mental illness is costly to employers. According to the National Business Group on Health, mental illness causes more days of work loss and work impairment than many other chronic conditions such as diabetes, asthma, and arthritis. Approximately 217 million days of work are lost annually due to productivity decline related to mental illness and substance-use disorders, costing U.S. employers $17 billion.

Mental Health America, a nonprofit dedicated to addressing the needs of those with mental illness and to promoting the mental health of all, says a depressed employee will often not seek treatment because they fear how it will affect their job and they are concerned about confidentiality.

“There’s sometimes the fear of repercussions,” said Dr. Beeson. “There’s a fear that people will be viewed as weaker or ‘less than,’ or depending upon the mental illness, maybe (having) a moral failing of their own.”

For example, in Los Angeles, a sales rep for a cable provider who suffered from a mental illness had to take a leave of absence from the job where he had worked for 24 years. When he was not ready to come back, the leave was extended, then extended again. Finally, he was fired for what the company called his “repeated, prolonged leaves of absence, which rendered him unable or unwilling to work.”

The employee sued, alleging his employers had allowed other sales reps to take more time off, including one who was out seven months, and another who was out 18 months. The employee had not previously had a negative performance review. The court sided with the employee, reasoning that under California’s Fair Employment and Housing Act, as long as a worker had a tentative return date, more time off could be a reasonable accommodation.

It can be difficult for an employee to win such a case, said Anthony D. Kuchulis, a lawyer with Barran Liebman in Portland, Ore., who represents employers and management in litigation. Still, he recommends employers stay out of such litigation, because while the employee will recover his or her attorney fees if successful on a stress disability claim, courts almost never let employers recover legal fees in cases they win.

“As a practical matter, I always recommend moving away from a risk management strategy based on strict legal analysis, and instead counsel companies to be generous and compassionate with employees reporting disabilities, even when the employee’s requests may exceed the company’s legal obligations to accommodate,” Kuchulis said.

Dr. Beeson said companies might consider employing a nurse, counselor, or psychologist on staff. “I think increasing access to services on-site is the exception, but probably one of the more effective models for employers to incorporate,” he said.

He agreed that a healthier workplace saves money. “The bottom line is important,” Dr. Beeson said. “I think performance goes up traditionally when people are healthier. It helps you accomplish your mission. It’s an investment in people’s lives as well as in the health of your business.”

It’s the law

There is another good reason for companies to accommodate people with mental illness: it is illegal not to, in the US and elsewhere.

An employer can’t discriminate against an employee who has a mental health condition. This includes firing someone, rejecting them for a job or promotion, or forcing them to take leave.

That doesn’t mean an employer has to hire or keep people in jobs they can’t perform or employ people who pose a significant risk of substantial harm to self or others.

But an employer cannot rely on myths or stereotypes about a mental health condition when deciding whether someone can perform a job or whether they pose a safety risk. To reject someone based on a mental health condition, the employer must have objective evidence that the person can’t perform their job duties, or that they would create a significant safety risk, even with a reasonable accommodation.

Squadrito said employees who recognize they have depression are far from a liability—they can be an asset. That type of introspection lends itself to greater creativity, a tremendous commodity to a public relations firm.

“Being self-aware also brings out the creativity in people,” she said. “[The presence of a mental illness] doesn’t hinder me from hiring anybody.”

Five tips for employers

A healthy and happy workforce is a productive workforce. How can managers ensure their employees maintain their mental health? Dr. Beeson offers five simple tips that can employers can implement:

_________________________________________