February 22, 2019

The biggest problem for city centres is a lack of high skilled jobs

The Centre for Cities, in partnership with George Capital, has mapped the UK cities with the strongest city centre economies in the UK, and identified their common features. The report City Centres: Past, Present and Future found that focusing on the struggles of certain high streets ignores the success of well-performing city centres and misdiagnoses the core problem: insufficient footfall in city centres due to a lack of jobs.

The Centre for Cities, in partnership with George Capital, has mapped the UK cities with the strongest city centre economies in the UK, and identified their common features. The report City Centres: Past, Present and Future found that focusing on the struggles of certain high streets ignores the success of well-performing city centres and misdiagnoses the core problem: insufficient footfall in city centres due to a lack of jobs.

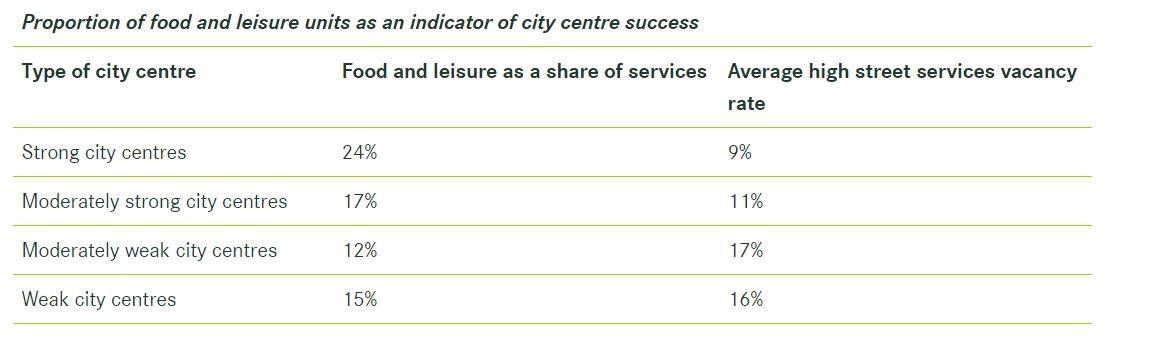

Successful city centres feature fewer shops but are supported by ‘knowledge-based’ office jobs – such as those in marketing, finance and law. As online retailers draw customers away from traditional shops, well-paying jobs in knowledge-based industries create a consumer market for high street restaurants, bars and other leisure activities to thrive.

Several regional cities such as Manchester, Birmingham (Brindleyplace pictured) and Liverpool have performed well in the last two decades at growing their city centre workforces, laying the foundations for strong city centre economies

Several regional cities such as Manchester, Birmingham (Brindleyplace pictured) and Liverpool have performed well in the last two decades at growing their city centre workforces, laying the foundations for strong city centre economies

The report shows the main challenge for poorly performing high streets is not the internet. It is the lack of skilled workers and demand to make the shift away from retail and towards high-knowledge and leisure services.

City councils require extra support and funding from Government to develop and deliver strategies that shift city centres away from retail, and towards office-based jobs and leisure. Meanwhile, councils with strong city centres should ensure a continued pipeline of high-quality office space to sustain the demand for bars, restaurants and other leisure venues.

The report concludes that to support city centres, the Government should treat them as strategic infrastructure projects, similar to transport.

It makes three key recommendations. First, it calls upon the Chancellor allow city leaders to access to the National Productivity Investment Fund to invest in making city centres more attractive places for businesses and employees. Second, it urges the Government to offer all city centres exemptions from commercial-to-residential conversions to protect valuable office space. Finally, more investment in skills for cities’ residents is necessary to create the educated workforce that future city centres need to thrive.

London is among the cities with the fewest empty commercial units in their city centres. Looking outside the capital, strong regional cities such as Liverpool, Birmingham, Manchester and Reading also have fewer commercial unit vacancies in their city centres than average.

At the other end of the spectrum Newport, Bradford and Wigan have the most city centre vacancies. These struggling city centres share a common characteristic: too many cheap retail units and a lack of quality office space, restaurants, cafes and bars. Their over-reliance on traditional retail means that they have struggled to compete with the popularity of online shopping.

Commenting on the findings, Centre for Cities Chief Executive Andrew Carter said: “This research shows that it is not all doom and gloom on the high street, despite the headlines. However future city centres are likely to look very different to today. We must remember that a successful high street is the result, not the driver, of a successful city economy and take a more holistic approach to regenerating city centres – including allowing councils to access infrastructure funding as well as money set aside for high street regeneration. Instead of trying to replace failed shops with more retail, investors and policy makers should focus their strategies on making struggling city centres attractive places to do business and spend leisure time – not just to shop.”