July 1, 2019

The biggest problem with open plan offices is how they are used

For decades the trend among workplaces has seen employees moving out of individual offices and into open plan spaces. This has not always been successful, with the open-plan approach receiving significant criticism. The key issues are distraction and noise, which apparently leads to uncooperative behaviour, distrust and negative personal relationships, and the lack of privacy and sense of being universally observed. Now that the internet connectivity is available almost everywhere and thus allows much more flexible working, the question arises: What might the set-up of an ideal workplace environment look like today?

For decades the trend among workplaces has seen employees moving out of individual offices and into open plan spaces. This has not always been successful, with the open-plan approach receiving significant criticism. The key issues are distraction and noise, which apparently leads to uncooperative behaviour, distrust and negative personal relationships, and the lack of privacy and sense of being universally observed. Now that the internet connectivity is available almost everywhere and thus allows much more flexible working, the question arises: What might the set-up of an ideal workplace environment look like today?

One response to the problems of open-plan spaces is simply to stop using them, as Ikea has done recently, structuring new spaces using its own taste for furniture design. But to be honest, I don’t see much of a difference to traditional workplaces based on the office “cubicle” – have a look and decide for yourself.

A variety of approaches aimed at designing better open-plan spaces include the following ideas: use private offices surrounding a hub of a common area, purchase movable barriers so people can create private space as needed, create larger offices with two or three work areas, install cubicles with cathedral ceilings, skylights and tall windows, or introduce a work-from-home policy – while renting space for group meetings as required.

We had the opportunity to experiment with creating better open-plan spaces at our public university in Denmark when a group of ten researchers moved offices, so we thought to try and put some of these ideas into practice.

An experiment in open plan office design

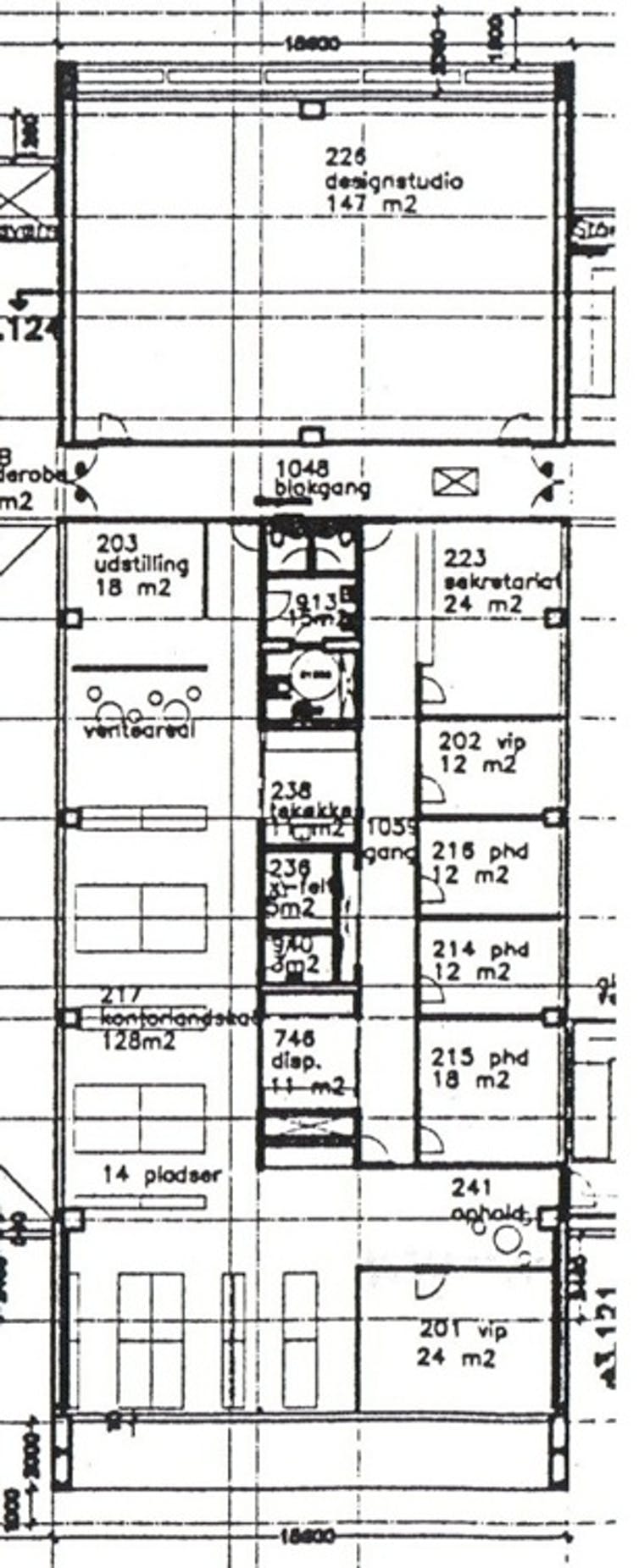

The open-plan design for the space we came up with looked like this (right):

The group’s response was fairly neutral, although some colleagues had doubts they could work in such an environment. We agreed to a six-month trial period, with the following prerequisites:

- office space for permanent staff, plus flexible work units for guests;

- a combination of working and social (informal) environment;

- opportunities for spontaneous discussions, but also quiet areas to do concentrated work, and

- generating and maintaining high acceptance within the staff.

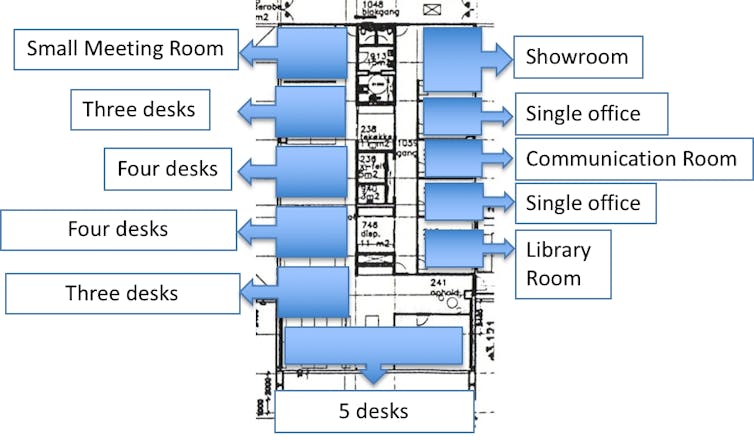

We first defined different areas: an office space with desks, a social area containing kitchen and couches, enclosed meeting rooms for discussions, rooms to go and make calls, and silent corners for quiet reading.

This meant the group no longer had fixed telephone lines. Instead, everyone used a VOIP smartphone app, Skype for Business, which meant it was possible to sit anywhere and still make and take calls over an internet connection.

Having passed legal and other requirements, the group were asked about their preferences, and a seating plan was drawn up. For example, it was decided that the course coordinators should remain in their own office, because they are generally involved in a lot of meetings and phone calls which would be difficult to incorporate into an open office space.

Consequently, the plan looked like this (the kitchen and restroom area are next to the small meeting room, and not shown).

What we learned

The trial period of six months passed – this was in 2014, and the office is still in its initial form today. However, there have been problems during this time.

For example, it was not always clear in which situations one should move to another room. The solution was to ensure that each new employee had the rules explained to them. Sometimes people booked the communication or library rooms for all-day meetings, which meant they were out of use for others. This problem was solved by making it a requirement that regular meeting rooms were booked. Of course, sometimes discussions or phone calls in the open-plan area could become loud or lengthy enough to disturb others, necessitating a reminder that other rooms were available for that purpose.

[perfectpullquote align=”right” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]You really need to consider what sort of work is suitable for different kinds of office set-ups[/perfectpullquote]

In general, many positive aspects appeared to be true. To some extent, it improved team working, spontaneous collaboration, and cross-fertilisation of ideas in shared spaces.

What have we learned and what can we recommend to others? Well, an open office plan is not by default a good or bad thing. As always, you need to have a strategic approach behind it to make it work, and you need to consider that these designs can even have the opposite effect of hurting relationships.

First, you really need to consider what sort of work is suitable for different kinds of office set-ups. For instance, people who work in sales or customer support typically spend much of their time talking or receiving visitors, making it impossible not to disturb others (at least those not doing the same), so they need a different environment.

Second, the most difficult part is to ensure that the rules are followed consistently. Open-plan spaces can only work in the long run if all those working there stick to the rules and remind others of them. It’s very important that the top management lead from the front and aren’t hidden away in their own office, divorced from the experiences of their staff. Hence, it is key that group leaders not only share the same office space, but also do not necessarily get the “best desk” – the one with the most privacy, for example – it’s important to show that the rules have the support of the leadership, in theory and in practice.

Third, consider the working atmosphere such an office creates: it tends to lead to an open environment in which behaviour is visible from the time an employee arrives at work – to who people are talking with and, often, what they are talking about. This can be seen as positive, fostering a feeling of togetherness. For others such transparency can be uncomfortable.

Last, it is important to note that creative work depends upon many factors: our research published this year indicates that the impulsiveness of team members plays an important role in their productivity. So overall, it has never been just about the open-plan office itself (which everybody seems to hate) but about each individual who spends their time working there – and how they make the best of it.

This piece also appears in The Conversation

Main image: Inside the panopticon at Presidio Modelo, Isla de la Juventud, Cuba. By I, Friman, published under a creative commons licence.

Prof. Dr. Alexander Brem is Full Professor and Chair, Friedrich-Alexander-University Erlangen-Nürnberg, Honorary Professor,, University of Southern Denmark