One day, news will emerge from Dubai of a new development that doesn’t break some record or other, or at least one that isn’t solely about the size of a building. The latest example of the Emirati obsession with scale is the plan by developers DMCC, the people who brought you the Jumeirah Lake Towers, to create the world’s largest commercial office building as part of a 107,000 sq m development of their business park. Although still in the development stage, the developers have their eyes on usurping the current holder of the tallest office crown, Taipei 101, the 509m-high building which was the world’s tallest tower of any sort until the Burj Khalifa came along in 2010. In their press announcement the developers claim the new tower will act as a magnet for multinationals, although not everybody is quite so enamoured of the idea that tall is best.

One of them is architect Frank Gehry, who took particular exception to the towers that spear the Dubai skyline and other boom towns in Asia. In a recent interview in Foreign Policy magazine, he derided them as ‘cheap’ and ‘anonymous’ and revealed his initial misgivings about his work on the Guggenheim in the neighbouring emirate of Abu Dhabi as a result.

‘The worst thing is when you go to places like Dubai,’ he said. ‘They’re on steroids, but they just end up looking like American or European cities with these anonymous skyscrapers – like every cruddy city in the world. One would hope there would be more support from within these places for architecture that responds to the place and culture. That’s what I’m trying to do, but, man, no one else seems to be involved with it. It’s just cheap copies of buildings that have already been built somewhere else.’

There are suspicions in the developed world’s cruddy cities that big and clever are two entirely different things. While it’s true that in  London, which has a longstanding mistrust of skyscrapers, not many bad words have been heard about The Shard, people seem rather less enamoured of the Scalpel, the Cheesegrater, and the Walkie Talkie.

London, which has a longstanding mistrust of skyscrapers, not many bad words have been heard about The Shard, people seem rather less enamoured of the Scalpel, the Cheesegrater, and the Walkie Talkie.

It was notable that the designers of the new Google HQ in King’s Cross made direct reference to The Shard in their recent announcements, letting everybody know it was actually bigger than Renzo Piano’s landmark, except that it was lying down, making it a ‘groundscraper’ of all things.

For those who don’t like tall buildings, the news from lift manufacturer Kone that it had developed a new form of cabling that would allow lift shafts to double in size will have been bad news. The height of buildings is considerably constrained by the means to get up them in that at some point the weight of the ropes needed to raise lifts is unsustainable. Kone believes it has overcome that problem with a carbon fibre rope that could allow single lift shafts to extend more than the height of the Burj Khalifa.

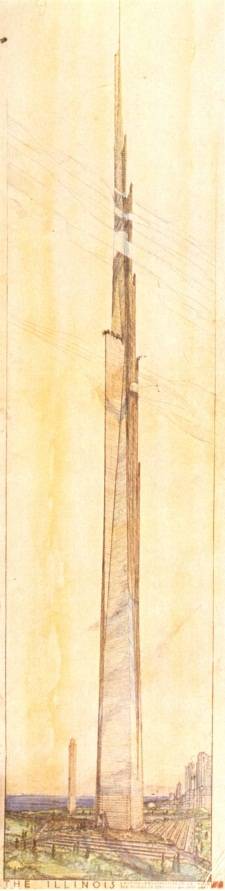

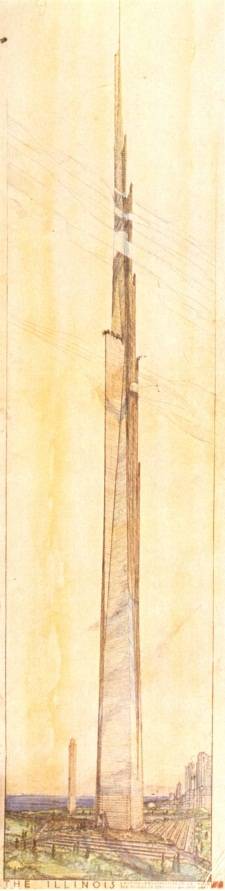

It was this constraint that prevented Frank Lloyd Wright realising his dream of creating a mile high tower called The Illinois (right). He might have different problems now that would force him to abandon his project. The USA, formerly home of the skyscraper has conspicuously fallen out of love with them. Earlier this year, the Chicago based Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitats reported that of the 66 buildings of 200m or more opened worldwide in 2012, a third opened in China, with four in Guangzhou alone. The whole of the US could only offer two.

Paris meanwhile is publicly agonising over a slew of 12 new tall buildings which are set to overturn the 40 year ban on buildings of more than seven floors that came about following the outcry over the 59 storey Tour Montparnasse. The new buildings are to be developed outside of the City centre of Paris and will not measure up by Asian standards but will still mark the skyline.

Inevitably the developments are sold on the basis of the architects behind them. Jean Nouvel has plans for twin leaning towers, one of 175m high, the other 115m on the Rive Gauche in the 13th arrondissement. In the north of the city, Renzo Piano has designed a 160m-high tower which will house law courts.

Of course, such buildings are seen as a way of emphasising the fact that any particular place is a world city, opening its arms to global businesses and the people who work for them. That is why cities employ the world’s leading architects to come up with them. But that can also make the buildings jar with their surroundings. London, Paris and New York may be world cities but they are still themselves too. This is the main complaint of those who oppose such buildings and is why the inhabitants of a city may never learn to love a building that could have been made for anywhere.

Or maybe they’ll be absorbed into the skyline. None of the buildings proposed for Paris is taller than the Eiffel Tower which itself was unloved when first created. The founder of the Arts & Crafts movement William Morris was in Paris a few months after the opening of the new Eiffel Tower, then the world’s tallest buildings and the centrepiece of the 1889 Exposition Universelle. A possibly apocryphal story goes that Morris spent a great deal of time in the Tower’s restaurant. A waiter said to him, ‘You are certainly impressed with our Tower, monsieur!’ ‘Impressed?’ replied Morris. ‘This is the only place in Paris where I can avoid seeing the thing.’

July 3, 2013

The world’s enduring love hate relationship with its tall buildings

by Mark Eltringham • Architecture, Comment, Property

One day, news will emerge from Dubai of a new development that doesn’t break some record or other, or at least one that isn’t solely about the size of a building. The latest example of the Emirati obsession with scale is the plan by developers DMCC, the people who brought you the Jumeirah Lake Towers, to create the world’s largest commercial office building as part of a 107,000 sq m development of their business park. Although still in the development stage, the developers have their eyes on usurping the current holder of the tallest office crown, Taipei 101, the 509m-high building which was the world’s tallest tower of any sort until the Burj Khalifa came along in 2010. In their press announcement the developers claim the new tower will act as a magnet for multinationals, although not everybody is quite so enamoured of the idea that tall is best.

One of them is architect Frank Gehry, who took particular exception to the towers that spear the Dubai skyline and other boom towns in Asia. In a recent interview in Foreign Policy magazine, he derided them as ‘cheap’ and ‘anonymous’ and revealed his initial misgivings about his work on the Guggenheim in the neighbouring emirate of Abu Dhabi as a result.

‘The worst thing is when you go to places like Dubai,’ he said. ‘They’re on steroids, but they just end up looking like American or European cities with these anonymous skyscrapers – like every cruddy city in the world. One would hope there would be more support from within these places for architecture that responds to the place and culture. That’s what I’m trying to do, but, man, no one else seems to be involved with it. It’s just cheap copies of buildings that have already been built somewhere else.’

There are suspicions in the developed world’s cruddy cities that big and clever are two entirely different things. While it’s true that in London, which has a longstanding mistrust of skyscrapers, not many bad words have been heard about The Shard, people seem rather less enamoured of the Scalpel, the Cheesegrater, and the Walkie Talkie.

London, which has a longstanding mistrust of skyscrapers, not many bad words have been heard about The Shard, people seem rather less enamoured of the Scalpel, the Cheesegrater, and the Walkie Talkie.

It was notable that the designers of the new Google HQ in King’s Cross made direct reference to The Shard in their recent announcements, letting everybody know it was actually bigger than Renzo Piano’s landmark, except that it was lying down, making it a ‘groundscraper’ of all things.

For those who don’t like tall buildings, the news from lift manufacturer Kone that it had developed a new form of cabling that would allow lift shafts to double in size will have been bad news. The height of buildings is considerably constrained by the means to get up them in that at some point the weight of the ropes needed to raise lifts is unsustainable. Kone believes it has overcome that problem with a carbon fibre rope that could allow single lift shafts to extend more than the height of the Burj Khalifa.

It was this constraint that prevented Frank Lloyd Wright realising his dream of creating a mile high tower called The Illinois (right). He might have different problems now that would force him to abandon his project. The USA, formerly home of the skyscraper has conspicuously fallen out of love with them. Earlier this year, the Chicago based Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitats reported that of the 66 buildings of 200m or more opened worldwide in 2012, a third opened in China, with four in Guangzhou alone. The whole of the US could only offer two.

Paris meanwhile is publicly agonising over a slew of 12 new tall buildings which are set to overturn the 40 year ban on buildings of more than seven floors that came about following the outcry over the 59 storey Tour Montparnasse. The new buildings are to be developed outside of the City centre of Paris and will not measure up by Asian standards but will still mark the skyline.

Inevitably the developments are sold on the basis of the architects behind them. Jean Nouvel has plans for twin leaning towers, one of 175m high, the other 115m on the Rive Gauche in the 13th arrondissement. In the north of the city, Renzo Piano has designed a 160m-high tower which will house law courts.

Of course, such buildings are seen as a way of emphasising the fact that any particular place is a world city, opening its arms to global businesses and the people who work for them. That is why cities employ the world’s leading architects to come up with them. But that can also make the buildings jar with their surroundings. London, Paris and New York may be world cities but they are still themselves too. This is the main complaint of those who oppose such buildings and is why the inhabitants of a city may never learn to love a building that could have been made for anywhere.

Or maybe they’ll be absorbed into the skyline. None of the buildings proposed for Paris is taller than the Eiffel Tower which itself was unloved when first created. The founder of the Arts & Crafts movement William Morris was in Paris a few months after the opening of the new Eiffel Tower, then the world’s tallest buildings and the centrepiece of the 1889 Exposition Universelle. A possibly apocryphal story goes that Morris spent a great deal of time in the Tower’s restaurant. A waiter said to him, ‘You are certainly impressed with our Tower, monsieur!’ ‘Impressed?’ replied Morris. ‘This is the only place in Paris where I can avoid seeing the thing.’