It is perhaps the most common misconception of evolutionary theory that all animals are somehow evolving towards some end point – meaning us. This notion is perhaps best summed up when a sceptic asks: “If we have evolved from monkeys, why are there still monkeys?” The lesser of the two problems with this is its solipsistic assumption that humans are the pinnacles of life and that, if evolution were true, all species would eventually evolve into people.

It is perhaps the most common misconception of evolutionary theory that all animals are somehow evolving towards some end point – meaning us. This notion is perhaps best summed up when a sceptic asks: “If we have evolved from monkeys, why are there still monkeys?” The lesser of the two problems with this is its solipsistic assumption that humans are the pinnacles of life and that, if evolution were true, all species would eventually evolve into people.

The bigger (and related) issue is that the question overlooks the fact that each species is already pretty much perfectly adapted to whatever environmental niche it inhabits at any particular time. It is only when that niche changes that the organism has to adapt to its changing surroundings and conditions, which is why many species continue to thrive almost unchanged over thousands or even millions of years. They have no need to evolve into a human or anything else.

This is the reason there is so much diversity of life on Earth. Yet, precisely because we’re humans we prefer this level of complexity and uncertainty to be simplified into patterns and narrative concepts such as the tree of life and the Ascent of Man.

Design evolution

A similar process can be discerned in the way we talk about the evolution of workplace design. I won’t pick on any particular one of the numerous histories of office design you can find online but any you care to look up is likely to begin with the starched clerical workers in Frank Lloyd Wright’s design for the Larkin Building from 1903 and wind up with a millennial on an orange slide. Along the way it will stop to have a pop at Frederick Taylor, cubicles and open plan before suggesting that something or other is dead and needs to be replaced because the pinnacle of office design has been achieved and you need to ascend too.

This idea is a compelling trap and it is one that Juriaan van Meel swerves neatly in his book Workplaces Today by treating the workplace ecosystem as something that can be subject to the same principles of taxonomy as the natural world.

Of course, he’s not the first person to turn to classification as a way of challenging the idea of an evolution procession towards a universally idealised form of office design. He doesn’t avoid the history of the office and the fact that it remains in a perpetual state of flux as it adapts to the changing needs of organisations, technology and people.

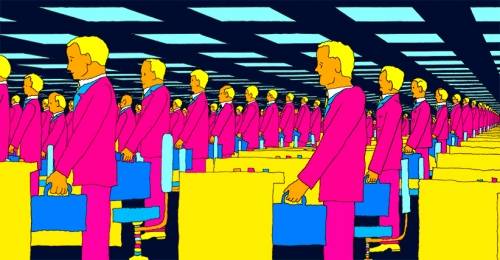

He also has little time for the mechanised and potentially dehumanising effects of an incorrect office design, especially one rooted in command and control management styles. He illustrates this point with a striking image from the work of Norwegian artist Hariton Pushwagner (right).

He also has little time for the mechanised and potentially dehumanising effects of an incorrect office design, especially one rooted in command and control management styles. He illustrates this point with a striking image from the work of Norwegian artist Hariton Pushwagner (right).

One of his progenitors in establishing a classification system for office design forms is Frank Duffy, who he cites throughout the book and who defined many of the ways we still talk about offices. Duffy is perhaps the person who popularised the taxonomical idea by combining the organisational design thinking of management theory with notions of how that might be transposed into the physical environment and used to define the various and evolving forms of workplace design.

A new office taxonomy

Whereas Duffy was content to stick to just four areas of classification when he wrote prodigiously and influentially on the subject in the 1990s, van Meel is writing about a very different world and is therefore able to broaden his scope and taxonomy to include various forms of public, shared and domestic spaces as well as new, hybrid forms of office environments such as co-working spaces, typified by the Impact Hub in Amsterdam (top).

[perfectpullquote align=”right” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]Discussions about workplace design can become very slippery once the basics have been covered[/perfectpullquote]

The strength of the book, once it has established the key features, context and premise of each of its ten classifications, is that it is led by case studies and hence imagery and descriptions of real offices. This means that the author is free to shape his own thoughts while leaving the reader their own freedom to make up their own mind about any particular example.

The author is also refreshingly well aware of the limitations of workplace design and the ways in which occupiers and designers can address the more difficult questions about getting a design right.

As he sums up the issue in his epilogue: “The low criticality of workplace design does not mean that it is irrelevant or an entirely subjective matter. It does mean, however, that discussions about workplace design can become very slippery once the basics have been covered. It is fairly easy to discuss the appropriate air quality and temperature levels in an office because these are, well-studied aspects of workplace quality. More conceptual issues, however, such as the openness of workspaces or the freedom to work from home, are much more value laden and open to debate.”

This is indeed where the challenges of office design arise and the trick is always to develop the right form for the right environment, just as it is in Nature. Problems arise when this is not the case. As the author concludes: “The art and science of workplace design is to make optimal use of these possibilities and to create solutions that are efficient, attractive and meaningful.”

June 28, 2019

Office taxonomy and an increasingly diverse workplace ecosystem 0

by Mark Eltringham • Comment, Facilities management, Workplace design

The bigger (and related) issue is that the question overlooks the fact that each species is already pretty much perfectly adapted to whatever environmental niche it inhabits at any particular time. It is only when that niche changes that the organism has to adapt to its changing surroundings and conditions, which is why many species continue to thrive almost unchanged over thousands or even millions of years. They have no need to evolve into a human or anything else.

This is the reason there is so much diversity of life on Earth. Yet, precisely because we’re humans we prefer this level of complexity and uncertainty to be simplified into patterns and narrative concepts such as the tree of life and the Ascent of Man.

Design evolution

A similar process can be discerned in the way we talk about the evolution of workplace design. I won’t pick on any particular one of the numerous histories of office design you can find online but any you care to look up is likely to begin with the starched clerical workers in Frank Lloyd Wright’s design for the Larkin Building from 1903 and wind up with a millennial on an orange slide. Along the way it will stop to have a pop at Frederick Taylor, cubicles and open plan before suggesting that something or other is dead and needs to be replaced because the pinnacle of office design has been achieved and you need to ascend too.

This idea is a compelling trap and it is one that Juriaan van Meel swerves neatly in his book Workplaces Today by treating the workplace ecosystem as something that can be subject to the same principles of taxonomy as the natural world.

Of course, he’s not the first person to turn to classification as a way of challenging the idea of an evolution procession towards a universally idealised form of office design. He doesn’t avoid the history of the office and the fact that it remains in a perpetual state of flux as it adapts to the changing needs of organisations, technology and people.

One of his progenitors in establishing a classification system for office design forms is Frank Duffy, who he cites throughout the book and who defined many of the ways we still talk about offices. Duffy is perhaps the person who popularised the taxonomical idea by combining the organisational design thinking of management theory with notions of how that might be transposed into the physical environment and used to define the various and evolving forms of workplace design.

A new office taxonomy

Whereas Duffy was content to stick to just four areas of classification when he wrote prodigiously and influentially on the subject in the 1990s, van Meel is writing about a very different world and is therefore able to broaden his scope and taxonomy to include various forms of public, shared and domestic spaces as well as new, hybrid forms of office environments such as co-working spaces, typified by the Impact Hub in Amsterdam (top).

[perfectpullquote align=”right” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]Discussions about workplace design can become very slippery once the basics have been covered[/perfectpullquote]

The strength of the book, once it has established the key features, context and premise of each of its ten classifications, is that it is led by case studies and hence imagery and descriptions of real offices. This means that the author is free to shape his own thoughts while leaving the reader their own freedom to make up their own mind about any particular example.

The author is also refreshingly well aware of the limitations of workplace design and the ways in which occupiers and designers can address the more difficult questions about getting a design right.

As he sums up the issue in his epilogue: “The low criticality of workplace design does not mean that it is irrelevant or an entirely subjective matter. It does mean, however, that discussions about workplace design can become very slippery once the basics have been covered. It is fairly easy to discuss the appropriate air quality and temperature levels in an office because these are, well-studied aspects of workplace quality. More conceptual issues, however, such as the openness of workspaces or the freedom to work from home, are much more value laden and open to debate.”

This is indeed where the challenges of office design arise and the trick is always to develop the right form for the right environment, just as it is in Nature. Problems arise when this is not the case. As the author concludes: “The art and science of workplace design is to make optimal use of these possibilities and to create solutions that are efficient, attractive and meaningful.”