October 23, 2017

An environmental psychology perspective on workplace design

I recently had the pleasure of travelling to Cape Town to present a keynote address at the Dare to Lead conference organised by Green Building Council South Africa (GBCSA). I had just 20 minutes to speak on a psychologist’s view of health, wellbeing and performance; that’s a huge subject area and pretty much my whole career condensed down to the typical time it takes to boil a pan of potatoes. So, I focused on just three psychological theories: motivation, personality and evolutionary psychology.

I recently had the pleasure of travelling to Cape Town to present a keynote address at the Dare to Lead conference organised by Green Building Council South Africa (GBCSA). I had just 20 minutes to speak on a psychologist’s view of health, wellbeing and performance; that’s a huge subject area and pretty much my whole career condensed down to the typical time it takes to boil a pan of potatoes. So, I focused on just three psychological theories: motivation, personality and evolutionary psychology.

Motivation Theory & Basic Needs

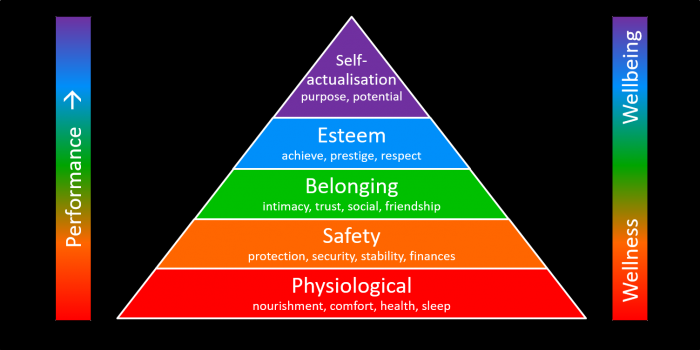

I am a bit of a fan of Maslow’sHierarchy of Needs model. Maslow proposed that there are a number of levels of human needs that each must be met before proceeding to the next level. The lower levels relate to basic needs like health, safety and security. Upper levels relate to social belonging, recognition and respect.

I am a bit of a fan of Maslow’sHierarchy of Needs model. Maslow proposed that there are a number of levels of human needs that each must be met before proceeding to the next level. The lower levels relate to basic needs like health, safety and security. Upper levels relate to social belonging, recognition and respect.

Only when we have met all levels can we self-actualise and perform to our maximum potential. I am indebted to Kate Lister for pointing out that the lower levels relate to health (wellness) and the upper ones to wellbeing. So, Maslow’s model nicely connects my subject areas of health, wellbeing and performance.

I have often quoted Tim Oldman, of the Leesman Index, who found that only 53 percent of some 200,000 respondents reported that their offices support their productivity – which is a damming indictment of our design and architectural industries. Furthermore, my reanalysis of the Leesman Index data showed that the basic (hygiene or environmental) factors, such as temperature, noise and air quality, have the least satisfaction yet are considered the most important factors. Therefore, before considering workplace design factors like colour, breakout/social spaces, funky furniture and slides etc, which the workplace design industry often appears to dwell on, we need to resolve these basic design requirements.

These basic factors have also been proven to have a huge impact on performance. A few years ago, Adrian Burton and I conducted a literature review of studies showing a direct effect of a range of environmental factors (noise, temperature, light, space etc) on performance. Our initial results yielded a range of effects of 0 percent to 160 percent, which is unbelievable for most people, never mind those more sceptical financial directors. However, using an expert panel, we weighted results by the place where the study was conducted (e.g. real world versus laboratory), the type of performance measure (e.g. embedded metric versus self-assessment) and the type of activity and how long it would be carried out in the office (e.g. computing use versus mental arithmetic).

The result was that the upper effect on performance for each individual factor ranged from just 2 percent to 4 percent. Whilst this is more realistic, it also on the low side. However, I believe that the impact of each factor can be added, but not linearly. Furthermore, the World Green Building Council, and others, have reported that the cost of a building is approximately 10 percent of the total cost of running a business, with staff salaries being the highest one. Based on generated revenue, I estimate that a 5 percent to 7 percent increase in performance could therefore cover all property costs.

Personality theory and designing for all

Many introverts have made considerable contributions to society and business. However, as Susan Cain pointed out, we tend to take more notice of the extroverts and as a consequence many modern workplaces appear to be designed with the extrovert in mind. These colourful, buzzy stimulating environments can be overwhelming for the introverts leading to stress, absenteeism an impeded performance. Furthermore, my own research has shown that extroverts spend less time in the office, and when in the office they are away from their desk in “meetings” – so we appear to design our workplaces for the people who are not actually present.

Extroverts are social animals preferring to spend time with others, they are thrill-seeker, risk takers, like big ideas and speak off the cuff. On the other hand, introverts prefer their own company, they take more time mulling things over, they welcome detail and they tend not to speak out in meetings (but they are listening and will send you a lengthy email after the meeting). Psychologists believe the difference between introverts and extroverts is due to our natural level of arousal. When our state of arousal is at its optimum then we perform to our maximum, if we are over stimulated we become stressed then performance decreases and when we are under-stimulated will feel fatigued and performance also decreases. This relationship between arousal is illustrated by the Yerkes-Dodson inverted-U shaped curve.

We believe that extroverts have a natural low level of arousal so seek stimulation to perform optimally. In contrast, introverts have a natural high level of arousal so seek more calming environments to perform at their peak. However, the task being performed has a confounding effect as complex tasks are stimulating and repetitive or monotonous tasks diminish stimulation. As a consequence, extroverts carrying out simple tasks perform better in a stimulating environment whereas introverts conducting complex tasks will require a calming environment. The challenge is how to design workplaces that can accommodate a range of personality types (and not just introverts versus extroverts) conducting different tasks.

I believe the start to the solution is to profile the team, or department, and design the main workspace to best suit the dominant personality type and activities. This is not so arduous as it first seems because we know that certain personality types are attracted to particular jobs, and also most organisations assess personality at the recruitment stage (but then ignore it and locate everyone in the same space). For example, provide a calming base space for say introverted analysts, researchers or developers, but provide a stimulating base space for more extroverted sales or marketing staff. However, remember that introverts will still need spaces to meet and interact etc, whereas extroverts will occasionally need spaces for privacy or chilling etc. Offer staff a wide choice of work-settings, away from their desk, and empower them to use the spaces as and when required.

Evolutionary psychology and innate workplace design preferences

Human physiology has evolved over millennia to ensure the survival of our species. Evolutionary psychologists believe that our brains, our cognitive processes, have also evolved over time. The problem is that we evolved all this time to survive on the African Savanah and we have only worked in the modern office for a hundred or so years. The brain is therefore lagging and our deep innate preference is for environments more in tune with the outside world. This doesn’t mean that we don’t desire more readily available shelter, food, comfort and wi-fi, or that we are not highly adaptive creatures, but perhaps we are to some extent “hard-wired” for a more natural environment.

Evolutionary psychologists, such as Stephen Kaplan, have promoted the benefits of biophilic workplace design since the mid-nighties. Kaplan proposed Attention Restoration Theory – when the ability to concentrate is restored by exposure to natural environments. People feel refreshed because nature provides a setting for “non-taxing involuntary attention” enabling our “directed” attention capacities to recover. An on-line survey of 7,600 respondents, found that those in biophilic environments reported 15% greater creativity and wellbeing. A study of a call-centre, with solid embedded objective metrics, found that operatives with views out, access to daylight and greenery had 6% higher performance than their colleagues in poorer spaces.

Researchers at Kansas University found that performance on lateral thinking (creativity) tests was increased by 50% after the subject sent 4-6 days back-packing in the American wilderness. Many researchers have concluded that the best way to resolve a problem is to get up from your desk and take a walk amongst nature. Physiological benefits of biophilia have also been found.Shinrin-Yoku is Japanese for “forest bathing” and researchers found that subjects immersed in in nature, compared to those in the city, had a reduced pulse rate, reduced blood pressure and reduced cortisol levels plus increased immune function – all indicators of lower stress levels. Similar benefits have been found indoors; Craig Knight has run a series of experiments where he has found that enriched environments, with plants and art, result in a higher number of creative ideas than lean workspaces. Bill Browning has documented the benefits of biophilia for some time and has produced clear guidance on how to create truly biophilic workplaces

My final reference is to the work of Robin Dunbar, an Oxford University anthropologist. He studies the social circle sizes of different primates and he found a direct correlation between their neocortex size and the social circle. He extrapolated that the cognitive limit to the number of people with whom we can maintain stable social relationships with is 150, termed Dunbar’s Number. The number has been verified through the average size of African villages, Christmas card lists and the number of Facebook friends; also Gore apparently split their manufacturing sites once they reach 150 workers. We often see large and deep plan office floorplates with 400 to 600 workers, but Dunbar’s Number implies that these are beyond the human scale and it is better to create smaller floorplates or break it up into smaller more comprehensible zones.

Workplace design hierarchy

I started with Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs as a means of connecting health wellbeing and performance. It occurred to me that there is probably a hierarchy of design needs. At the most basic level the workplace should offer shelter, sanitation (good toilets) and nutrition (coffee and places to eat). We then need the tools, equipment (technology and furniture) and facilities (meeting rooms) to complete the task in hand. As in Maslow, we also need a healthy, safe and secure environment. Our workplaces also need to be comfortable and offer the optimum environmental conditions, especially acoustics and temperature. Perhaps just above this need are our evolutionary psychology and biophilic needs, which impact on wellbeing. We then have our social needs, spaces for social interaction and collaboration, but they must be balanced with contemplation, privacy and the need for quiet, focus and concentration. But ultimately, we need a true choice of workspaces, accompanied by freedom, empowerment and trust, to ensure we perform to our maximum potential.

_______________________________________________

Nigel Oseland is an environmental psychologist, workplace strategist, change manager, author, and founder of the Workplace Consulting Organisation and Workplace Unlimited and one of Europe’s leading writers on workplace issues. This comment was originally posted on his own blog which you can find here along with a wealth of other ideas, information and thought leadership.

Nigel Oseland is an environmental psychologist, workplace strategist, change manager, author, and founder of the Workplace Consulting Organisation and Workplace Unlimited and one of Europe’s leading writers on workplace issues. This comment was originally posted on his own blog which you can find here along with a wealth of other ideas, information and thought leadership.