My trade is to ask questions about the workplace then make sense of the answers. That has been a particular challenge with the question, ‘what are offices today?’ What seems clear is that the various actors in the workplace ecosystem look at offices through very different eyes. Urban planning and development professionals still view offices as a distinct category of real estate and most real estate professionals view offices in terms of the delivery of floor space. Some things have changed,however. For some time, the hybrid economy of serviced offices has turned the product into a service. But, in many cases this has simply made the leasing of space simpler and more flexible.

My trade is to ask questions about the workplace then make sense of the answers. That has been a particular challenge with the question, ‘what are offices today?’ What seems clear is that the various actors in the workplace ecosystem look at offices through very different eyes. Urban planning and development professionals still view offices as a distinct category of real estate and most real estate professionals view offices in terms of the delivery of floor space. Some things have changed,however. For some time, the hybrid economy of serviced offices has turned the product into a service. But, in many cases this has simply made the leasing of space simpler and more flexible.

As Neil Usher says in his workessence blog, “while co-working is declared to be disrupting the institutional stuffed shirt that is the commercial rented sector, the sprouting centres come to increasingly resemble the corporate world at which their earlier incarnations cocked a snook”.

That may indeed be true for many serviced offices, and a few co-working hubs. But, what is happening now, in pockets of activity, appears to be that the “experience economy” is starting to pull offices through into a contemporary “place experience” sub-economy.

Rob Harris’ book Property and the Office Economy a decade ago, helped to simultaneously consolidate my thinking, and to spark new questions. In fact, it appears that we could have three perspectives on offices, as follows:

- Offices as a ‘product’ : floor area, for a price (rent)

- Offices as a ‘service’ : space and service, for a simple fee (daily, monthly, etc.)

- Offices as ‘experience’ : more than the sum of (a) + (b); attraction; added value;

The social office: how many followers does your office have?

Coworking

Companies like WeWork are creating a following, a community, of which inspiring places is just one (important) element. The corporate world is fighting back, and (again, in pockets) trying to emulate this “place experience” sub-economy. We all know the well-publicised examples, such as Google.

Behind all of this, of course, is the fact that increasingly we (us fortunate knowledge workers) often do not ‘have’ to be anywhere in particular. Sometimes we need to be with specific groups of people (meetings, workshops, events). Mostly, we can choose who to be with, and where to hang out. Though, not everyone can do this, and not all of the time, as Neil Usher also points out:

“…the more technology we deploy and the more reliant upon it and more in its service our careers become, the more we need closer human interaction, and the enablers of this. The more we push the boundaries, the less that work is an individual pursuit.”

But human interaction does not need to be in the corporate office. There are economic push-pull factors at work, which simply did not exist when the concept of the office originated, as a real estate ‘product’. Many office users are now consumers, with real choice. Larger employers are trying to attract people back to the office, in the knowledge that they can work somewhere ‘cooler’, or just more convenient.

What is this dynamic? What do we call it? – the “social office” perhaps? Does your office have “followers”? Will places have followers? Will Google hangouts not just be online? (scary thought, or exciting, depending on your viewpoint – could we see Google “hangouts” in every urban centre?)

Form and function have changed

Many commentators have predicted the ‘death of the office’. It is no closer to becoming true than the ‘paperless office’ was when Business Week predicted it in 1975. Mark Twain once said, “The reports of my death have been greatly exaggerated”. The same might be said of the office. Offices are certainly changing. Or, in many cases, ‘have changed’, almost to be unrecognisable to my parents and others who have not stepped into a contemporary office for a couple of decades.

Contemporary office space often looks very different to the way it did even a decade ago. And the activities and functions conducted by people in office space have changed – not entirely, but in relative proportions. Office work is less desk-bound, and more collaborative. Any Facilities Manager can prove this with utilization data, using sensor technology or a simple walk-about. Commonly, the general workstation-filled open-plan space is approximately 40 percent occupied, on average. But, meeting rooms are often fully utilized, and if you hang around long enough you will hear someone say, “There are no meeting rooms available. Let’s go across the road to [xyz]”. Xyz is usually a café, restaurant, or place where a group of people can get free meeting space in return for buying coffee (a kind-of reverse business model, in many cases!).

Dear planners… it’s all Sui Generis now

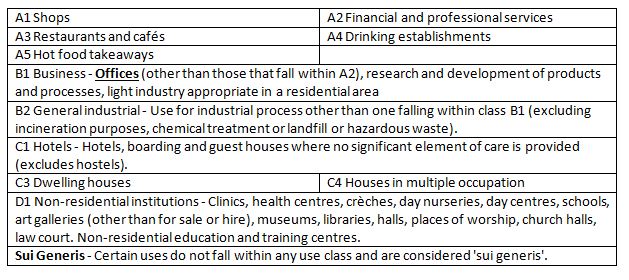

Take this last case in point. Urban planning is quite rigid in its terminology. But, if you spend a lot of time in and around urban areas, it is easy to find numerous examples of spaces being used for something different to their primary “Use Class”. In England, the legal “use” is defined by The Town and Country Planning (Use Classes) Order and managed by local government planning authorities. The owner of a space will generally need planning permission to change from one use class to another.

This is, of course, a matter of substantive use. These ‘use classes’ are listed in the table below (I have left out a few, for clarity purposes).

When is a hotel not a hotel? When is a café not a café? In the example above, between check-in times (most of the day), this hotel is an office, isn’t it? Or is it Sui Generis, the catch-all?So now, let’s reflect back to the over-flowing meeting room area in an office, in a central urban area. The meeting convener has decided to take her meeting across the road to a hotel. On arrival in the hotel lobby, she finds that she is not alone in doing so. In fact, the whole ground floor is filled with tables, where business people are meeting. Some are between meetings, working on laptops, and being served with coffee by the hotel staff. In many of the rooms upstairs, people staying in the city for a few days are similarly working at their slightly under-sized “office desk” provided by the hotel.

Property market data can be misleading – it’s about ‘product’

Property market data does not help us much, as it focuses on the old categories of primary ‘use classes’ discussed above. Property market data focuses on the product – the floor area (quantity) and rent, and occasionally other operating costs (price). It is the old economic model, trying to predict the demand for more floor area, and relative market prices.

Property market data does not help us much, as it focuses on the old categories of primary ‘use classes’ discussed above. Property market data focuses on the product – the floor area (quantity) and rent, and occasionally other operating costs (price). It is the old economic model, trying to predict the demand for more floor area, and relative market prices.

A casual glance at office property data in London, from a workplace strategist’s perspective, may suggest the demise of the office. Between May 2013 and April 2015 data shows that at least 2,639 office-to-residential applications were received, by London boroughs. As the London Councils report “at least 322 [were] fully occupied office spaces… around 39 per cent of those approvals granted for which occupancy information is available”. This is not just a London market phenomenon. The British Council for Offices (BCO) says that the current office-to-residential permitted development right is estimated to have led to more than 550,000 square metres of office space in

England being converted into residential use in 2014.

Is this indicating the demise of the office? The property data picture is mixed: part re-use of redundant office stock, but also driven by higher residential values. As would be expected, the latter has been the driver in much of Greater London. However, if one drives around the suburbs of almost any UK city, it takes little time to compile a list of vacant offices, for sale or ‘to let’. Often these office properties are in locations where conversion to alternative use, such as residential, would be inappropriate or unattractive. For example, these vacant offices may be in industrial areas or business parks.

Secondary office ‘product’ being replaced with service, or even experience

The BCO report10 concludes that “high office rents are resulting in a fresh development response across the UK, which may replace some (but probably not all) of the lost space” (i.e., office space lost due to conversion to residential use).

There is less data which describes the nature and quality of this new office space. Square metres of office space, as data, only provides an indicator of quantity, but not quality. For example, we should ask:

- Is the market simply losing tired old, or sub-standard, office space?

- Is it being replaced with fresh, light, airy and attractive office space?

- Is new space being delivered with additional functionality and a ‘service’ element?

- If so, will this new office space promote healthy, productive and creative activity?

Loss of poor quality office space may be a good thing for the economy of any country, if one believes (as workplace strategists surely do) that quantity of space is not the same as quality of space or place. Paying more, for a higher quality working environment, may ultimately make the workforce more comfortable, productive, and result ultimately in more successful occupier organizations. The BCO report acknowledges this, commenting on the data from one area of London:

“The replacement of secondary office floorspace (presumably at lower rents) by more expensive prime office floorspace is not necessarily undesirable. However, it can be detrimental to the local business base if the pace of change is too rapid.”

The speed of change may be a problem, clearly, if the poorer quality (and lower cost) space becomes unavailable in timescales which smaller businesses have insufficient time to respond to. But, in the medium term, albeit paying higher rents, they may adjust to subsequent benefits of their ability to attract staff, and to achieve higher staff satisfaction and productivity levels.

Consider the argument for the enlightened SME (small and medium sized enterprise): why should the workforce of a small firm expect to work in environments of far lower quality than their friends who work for larger companies? We know that often this is the case, but why should it be?

Offices, off the radar: the rise of co-working hubs and agile working

Interestingly, the BCO report suggests that “the office market does appear to be responding at least partly to shortages of cheaper or smaller office space, including through ‘hub’, ‘incubator’ or serviced office models”. This should be of great interest to workplace strategists – a watching brief is needed. This is a trend which will surely continue to grow.

The replacement of secondary office space, especially tired old poor quality space, may be a good thing, as discussed above. However, as it is replaced with serviced offices, co-working hubs, and various other entrepreneurial places, does it disappear ‘off the radar’ for property analysts?

Ramidus Consulting’s 2014 report estimated that 3% of the City of London office floor space was used by serviced offices, and that this had quadrupled since 1995. They also noted “about 60% of the centres have opened since 2008, despite the global financial crisis” suggesting we will see continued strong growth in serviced offices. The report stated:

“We estimate that there are 10,437 small occupiers (occupying space of less than 1,000 sq ft) in the City, of which 8,173 (78%) occupy conventional leased space, and 2,264 (22%) occupy serviced office space. If the number of small occupiers in the City was to grow by 10% over the next decade, and the proportion of small occupiers accommodated in serviced offices rose from its current 22% of the total to 35%, then the market for serviced offices would grow by 77% by 2025. This is in addition to potential demand from the growth of core and periphery business models from corporates; new business formation and in-movers and representative offices. For this reason, we consider it a cautious prediction to expect the market for serviced offices to double in size within the next decade.”

This may happen, over the next decade. But, the picture does not reflect how the new serviced office space is likely to be used. And therefore the metrics, and our property market language, will be wrong. When a small business decides to move into serviced offices, they will buy what they need as they grow. They are likely to use the new space more flexibly than their traditional leased space. They will share desks, and buy meeting room space when needed.

Hence, the serviced office space does not replace the traditional office space, like-for-like. Far more people are likely to be supported by the serviced office, in the same quantity of space. So, the ‘formal’ demand for office space reduces. But those people are working somewhere! They are in someone else’s office, or working at home, or in a hotel, or somewhere.

In respect of office use, the floor area metric is simply becoming far less relevant, as demonstrated above. We can no longer link knowledge workers to office floor space. But they are working somewhere – just ‘off the radar’.

As form and function change, our language must change too

Area

The ways in which we – that is, the media, professions, and people in general – describe offices, has not kept up with the reality of contemporary workplaces. There is too often a focus on what can be easily quantified, and a dearth of information where things are difficult to measure. These are just a few examples, some of which have been discussed above:

- Property market data is focused on floor area (square metres/feet), rent, and location. But a unit of office floor area, in a specific location, is not a commodity. So, property market data has wide margins. Rent varies significantly, based on many factors;

- These many factors have been captured into methodologies, and tested around the world, but rarely make it outside the world of academia. Assessing building performance, quantitatively or qualitatively, alongside comparison of market rent and operating costs, is still rare;

- Efficiency of office space use is now becoming, for many occupiers, more important that quantity of space. For an ‘agile’ workplace, there is now a limited connection between the quantity of space and the numbers of people supported by that space;

- The concepts of ‘place’ and ‘service’ are overtaking ‘space’ as a measure. The more that people, knowledge-workers in particular, can work almost anywhere, the more they need to be attracted to a great ‘place’. Or at least, the experience of ‘service’ that they would expect elsewhere.

- From an urban planning viewpoint, the contemporary concept of an ‘office’ is blurred into part-hotel, part-retail, and even residential. What is an office, today? And where is the office? For many, especially the growing number of freelance workers, the office is wherever there is somewhere to sit (or stand!), in relative comfort, and use a connected device.

- A desk and a chair were essentials in the era of paper and briefcases. The desk-based telephone came (and went, in many cases). The desk-top PC came (and again, went, in many cases). The laptop PC came, got lighter and smaller, and even that has often gone. Connected devices now mostly do not need desks – or even chairs. But we mostly sit down to ‘work’, and still mostly sit at flat surfaces – maybe a desk, or maybe just a table somewhere.

- Architects and designers slave over their CAD and BIM models, to create sustainable office buildings, and building services. But knowledge workers increasingly decide whether they need to travel to the office at all. And their corporate occupier teams are slowly recognizing the most sustainable solution may often be to have fewer offices, not just new sustainable offices.

The issues set out above demonstrate that the link between economic activity and the office ‘product’ is, today, rarely a simple a relationship. For much of contemporary life, it seems clear that the urban planning ‘use class’ of B1-Offices is no longer fit for purpose. We need to find different ways of describing the built asset product, its use as a service to organisations (occupiers), and increasingly the role of great space and places in the experience economy.

As the 60s song goes, “You’re everywhere and nowhere baby, that’s where you’re at”. Call it what you like, that’s where you’re sat.

This article is also available in Work&Place. Illustration Simon Heath @SimonHeath1

____________________________________

Paul Carder has over 20 years postgraduate experience in the corporate and consulting sectors, specializing in real estate (property) and facilities management/ workplace strategy, outsourcing, performance management and measurement. Currently Doctoral Researcher and Tutor at UWE Bristol, he is also publisher of Work & Place and Occupiers Journal which works with several partners around the world. paul.carder@occupiersjournal.com

Paul Carder has over 20 years postgraduate experience in the corporate and consulting sectors, specializing in real estate (property) and facilities management/ workplace strategy, outsourcing, performance management and measurement. Currently Doctoral Researcher and Tutor at UWE Bristol, he is also publisher of Work & Place and Occupiers Journal which works with several partners around the world. paul.carder@occupiersjournal.com

References:

1 Harris, R. (2005) Property and the Office Economy; Estates Gazette Books

2 https://workessence.com/without-you-im-nothing/

3 Pine, B. J., & Gilmore, J. H. (1999). The experience economy: Work is theatre & every business a stage. Harvard Business Press.

4 https://www.wework.com/

5 “The Office of the Future”, Business Week (2387), 30 June 1975: 48–70

6 For example, “Sense” from Condeco Software: https://www.condecosoftware.com/products/workspace-occupancy-sensor/

7 https://www.planningportal.gov.uk/permission/commonprojects/changeofuse

8 https://www.planningresource.co.uk/article/1363298/report-320-occupied-london-offices-lost-permitted-development-right

9 London Councils (2015), “The Impact of Permitted Development Rights for Office to Residential Conversions”, August.

10 British Council for Offices (2015), “Office-to-residential conversion”, September.

11 Ramidus Consulting (2014), “Serviced Offices and Agile Occupiers in the City of London”, City of London Corporation, October.

12 https://genius.com/Jeff-beck-hi-ho-silver-lining-lyrics/

January 25, 2019

The state of the workplace right now? Everywhere and nowhere, baby 0

by Paul Carder • Comment, Facilities management, Features, Premium Content, Property, Workplace design

As Neil Usher says in his workessence blog, “while co-working is declared to be disrupting the institutional stuffed shirt that is the commercial rented sector, the sprouting centres come to increasingly resemble the corporate world at which their earlier incarnations cocked a snook”.

That may indeed be true for many serviced offices, and a few co-working hubs. But, what is happening now, in pockets of activity, appears to be that the “experience economy” is starting to pull offices through into a contemporary “place experience” sub-economy.

Rob Harris’ book Property and the Office Economy a decade ago, helped to simultaneously consolidate my thinking, and to spark new questions. In fact, it appears that we could have three perspectives on offices, as follows:

The social office: how many followers does your office have?

Coworking

Companies like WeWork are creating a following, a community, of which inspiring places is just one (important) element. The corporate world is fighting back, and (again, in pockets) trying to emulate this “place experience” sub-economy. We all know the well-publicised examples, such as Google.

Behind all of this, of course, is the fact that increasingly we (us fortunate knowledge workers) often do not ‘have’ to be anywhere in particular. Sometimes we need to be with specific groups of people (meetings, workshops, events). Mostly, we can choose who to be with, and where to hang out. Though, not everyone can do this, and not all of the time, as Neil Usher also points out:

“…the more technology we deploy and the more reliant upon it and more in its service our careers become, the more we need closer human interaction, and the enablers of this. The more we push the boundaries, the less that work is an individual pursuit.”

But human interaction does not need to be in the corporate office. There are economic push-pull factors at work, which simply did not exist when the concept of the office originated, as a real estate ‘product’. Many office users are now consumers, with real choice. Larger employers are trying to attract people back to the office, in the knowledge that they can work somewhere ‘cooler’, or just more convenient.

What is this dynamic? What do we call it? – the “social office” perhaps? Does your office have “followers”? Will places have followers? Will Google hangouts not just be online? (scary thought, or exciting, depending on your viewpoint – could we see Google “hangouts” in every urban centre?)

Form and function have changed

Many commentators have predicted the ‘death of the office’. It is no closer to becoming true than the ‘paperless office’ was when Business Week predicted it in 1975. Mark Twain once said, “The reports of my death have been greatly exaggerated”. The same might be said of the office. Offices are certainly changing. Or, in many cases, ‘have changed’, almost to be unrecognisable to my parents and others who have not stepped into a contemporary office for a couple of decades.

Contemporary office space often looks very different to the way it did even a decade ago. And the activities and functions conducted by people in office space have changed – not entirely, but in relative proportions. Office work is less desk-bound, and more collaborative. Any Facilities Manager can prove this with utilization data, using sensor technology or a simple walk-about. Commonly, the general workstation-filled open-plan space is approximately 40 percent occupied, on average. But, meeting rooms are often fully utilized, and if you hang around long enough you will hear someone say, “There are no meeting rooms available. Let’s go across the road to [xyz]”. Xyz is usually a café, restaurant, or place where a group of people can get free meeting space in return for buying coffee (a kind-of reverse business model, in many cases!).

Dear planners… it’s all Sui Generis now

Take this last case in point. Urban planning is quite rigid in its terminology. But, if you spend a lot of time in and around urban areas, it is easy to find numerous examples of spaces being used for something different to their primary “Use Class”. In England, the legal “use” is defined by The Town and Country Planning (Use Classes) Order and managed by local government planning authorities. The owner of a space will generally need planning permission to change from one use class to another.

This is, of course, a matter of substantive use. These ‘use classes’ are listed in the table below (I have left out a few, for clarity purposes).

When is a hotel not a hotel? When is a café not a café? In the example above, between check-in times (most of the day), this hotel is an office, isn’t it? Or is it Sui Generis, the catch-all?So now, let’s reflect back to the over-flowing meeting room area in an office, in a central urban area. The meeting convener has decided to take her meeting across the road to a hotel. On arrival in the hotel lobby, she finds that she is not alone in doing so. In fact, the whole ground floor is filled with tables, where business people are meeting. Some are between meetings, working on laptops, and being served with coffee by the hotel staff. In many of the rooms upstairs, people staying in the city for a few days are similarly working at their slightly under-sized “office desk” provided by the hotel.

Property market data can be misleading – it’s about ‘product’

A casual glance at office property data in London, from a workplace strategist’s perspective, may suggest the demise of the office. Between May 2013 and April 2015 data shows that at least 2,639 office-to-residential applications were received, by London boroughs. As the London Councils report “at least 322 [were] fully occupied office spaces… around 39 per cent of those approvals granted for which occupancy information is available”. This is not just a London market phenomenon. The British Council for Offices (BCO) says that the current office-to-residential permitted development right is estimated to have led to more than 550,000 square metres of office space in

England being converted into residential use in 2014.

Is this indicating the demise of the office? The property data picture is mixed: part re-use of redundant office stock, but also driven by higher residential values. As would be expected, the latter has been the driver in much of Greater London. However, if one drives around the suburbs of almost any UK city, it takes little time to compile a list of vacant offices, for sale or ‘to let’. Often these office properties are in locations where conversion to alternative use, such as residential, would be inappropriate or unattractive. For example, these vacant offices may be in industrial areas or business parks.

Secondary office ‘product’ being replaced with service, or even experience

The BCO report10 concludes that “high office rents are resulting in a fresh development response across the UK, which may replace some (but probably not all) of the lost space” (i.e., office space lost due to conversion to residential use).

There is less data which describes the nature and quality of this new office space. Square metres of office space, as data, only provides an indicator of quantity, but not quality. For example, we should ask:

Loss of poor quality office space may be a good thing for the economy of any country, if one believes (as workplace strategists surely do) that quantity of space is not the same as quality of space or place. Paying more, for a higher quality working environment, may ultimately make the workforce more comfortable, productive, and result ultimately in more successful occupier organizations. The BCO report acknowledges this, commenting on the data from one area of London:

“The replacement of secondary office floorspace (presumably at lower rents) by more expensive prime office floorspace is not necessarily undesirable. However, it can be detrimental to the local business base if the pace of change is too rapid.”

The speed of change may be a problem, clearly, if the poorer quality (and lower cost) space becomes unavailable in timescales which smaller businesses have insufficient time to respond to. But, in the medium term, albeit paying higher rents, they may adjust to subsequent benefits of their ability to attract staff, and to achieve higher staff satisfaction and productivity levels.

Consider the argument for the enlightened SME (small and medium sized enterprise): why should the workforce of a small firm expect to work in environments of far lower quality than their friends who work for larger companies? We know that often this is the case, but why should it be?

Offices, off the radar: the rise of co-working hubs and agile working

Interestingly, the BCO report suggests that “the office market does appear to be responding at least partly to shortages of cheaper or smaller office space, including through ‘hub’, ‘incubator’ or serviced office models”. This should be of great interest to workplace strategists – a watching brief is needed. This is a trend which will surely continue to grow.

The replacement of secondary office space, especially tired old poor quality space, may be a good thing, as discussed above. However, as it is replaced with serviced offices, co-working hubs, and various other entrepreneurial places, does it disappear ‘off the radar’ for property analysts?

Ramidus Consulting’s 2014 report estimated that 3% of the City of London office floor space was used by serviced offices, and that this had quadrupled since 1995. They also noted “about 60% of the centres have opened since 2008, despite the global financial crisis” suggesting we will see continued strong growth in serviced offices. The report stated:

“We estimate that there are 10,437 small occupiers (occupying space of less than 1,000 sq ft) in the City, of which 8,173 (78%) occupy conventional leased space, and 2,264 (22%) occupy serviced office space. If the number of small occupiers in the City was to grow by 10% over the next decade, and the proportion of small occupiers accommodated in serviced offices rose from its current 22% of the total to 35%, then the market for serviced offices would grow by 77% by 2025. This is in addition to potential demand from the growth of core and periphery business models from corporates; new business formation and in-movers and representative offices. For this reason, we consider it a cautious prediction to expect the market for serviced offices to double in size within the next decade.”

This may happen, over the next decade. But, the picture does not reflect how the new serviced office space is likely to be used. And therefore the metrics, and our property market language, will be wrong. When a small business decides to move into serviced offices, they will buy what they need as they grow. They are likely to use the new space more flexibly than their traditional leased space. They will share desks, and buy meeting room space when needed.

Hence, the serviced office space does not replace the traditional office space, like-for-like. Far more people are likely to be supported by the serviced office, in the same quantity of space. So, the ‘formal’ demand for office space reduces. But those people are working somewhere! They are in someone else’s office, or working at home, or in a hotel, or somewhere.

In respect of office use, the floor area metric is simply becoming far less relevant, as demonstrated above. We can no longer link knowledge workers to office floor space. But they are working somewhere – just ‘off the radar’.

As form and function change, our language must change too

Area

The ways in which we – that is, the media, professions, and people in general – describe offices, has not kept up with the reality of contemporary workplaces. There is too often a focus on what can be easily quantified, and a dearth of information where things are difficult to measure. These are just a few examples, some of which have been discussed above:

The issues set out above demonstrate that the link between economic activity and the office ‘product’ is, today, rarely a simple a relationship. For much of contemporary life, it seems clear that the urban planning ‘use class’ of B1-Offices is no longer fit for purpose. We need to find different ways of describing the built asset product, its use as a service to organisations (occupiers), and increasingly the role of great space and places in the experience economy.

As the 60s song goes, “You’re everywhere and nowhere baby, that’s where you’re at”. Call it what you like, that’s where you’re sat.

This article is also available in Work&Place. Illustration Simon Heath @SimonHeath1

____________________________________

References:

1 Harris, R. (2005) Property and the Office Economy; Estates Gazette Books

2 https://workessence.com/without-you-im-nothing/

3 Pine, B. J., & Gilmore, J. H. (1999). The experience economy: Work is theatre & every business a stage. Harvard Business Press.

4 https://www.wework.com/

5 “The Office of the Future”, Business Week (2387), 30 June 1975: 48–70

6 For example, “Sense” from Condeco Software: https://www.condecosoftware.com/products/workspace-occupancy-sensor/

7 https://www.planningportal.gov.uk/permission/commonprojects/changeofuse

8 https://www.planningresource.co.uk/article/1363298/report-320-occupied-london-offices-lost-permitted-development-right

9 London Councils (2015), “The Impact of Permitted Development Rights for Office to Residential Conversions”, August.

10 British Council for Offices (2015), “Office-to-residential conversion”, September.

11 Ramidus Consulting (2014), “Serviced Offices and Agile Occupiers in the City of London”, City of London Corporation, October.

12 https://genius.com/Jeff-beck-hi-ho-silver-lining-lyrics/