November 14, 2014

EU institutions are not implementing their own green building policies

According to a report on EU news site euractiv.com, the various institutions of the European Union have been ‘unambitious’ in terms of delivering energy efficiency as part of their own buildings strategies. That is the key finding of a new study from the European Court of Auditors. which claims that green building standards and initiatives developed and promoted by the EU are not consistently employed for new buildings or as part of major renovation projects carried out by bodies such as the European Commission, European Parliament, EU Council and other institutions. The special report reveals shortcomings in the approach of these bodies, calls on the EU Commission to propose a common policy for reducing the carbon footprint of EU institutions and bodies and proposes the setting of an overall reduction target for greenhouse gas emissions by the year 2030. The report claims that it is through the design processes of a new building, or for a major renovation, that the greatest impact can be made on its energy performance and this should be the focus of its proposed new approach.

According to a report on EU news site euractiv.com, the various institutions of the European Union have been ‘unambitious’ in terms of delivering energy efficiency as part of their own buildings strategies. That is the key finding of a new study from the European Court of Auditors. which claims that green building standards and initiatives developed and promoted by the EU are not consistently employed for new buildings or as part of major renovation projects carried out by bodies such as the European Commission, European Parliament, EU Council and other institutions. The special report reveals shortcomings in the approach of these bodies, calls on the EU Commission to propose a common policy for reducing the carbon footprint of EU institutions and bodies and proposes the setting of an overall reduction target for greenhouse gas emissions by the year 2030. The report claims that it is through the design processes of a new building, or for a major renovation, that the greatest impact can be made on its energy performance and this should be the focus of its proposed new approach.

“Improving the energy performance of buildings will be a major challenge for the coming years,” the report said. “It is important that EU institutions and bodies set ambitious targets for their own buildings, if they want to reduce emissions.

Ladislav Balko, of the European Court of Auditors, said, “Paying attention to environmental performance in their daily operations is important not only for their own credibility but also for the credibility of the climate policy of the European Union.”

The report claims that EU institutions managed to reverse the trend of increasing greenhouse gas emissions caused by energy consumption in their buildings. Efforts to mitigate greenhouse gas emissions began on a larger scale in 2006. But a systematic approach focused on efficiency was lacking, the auditors found. Policies backed publicly by the institutions, such as the requirements of Green Public Procurement (GPP), were not put in place as a matter of course.

The GPP’s criteria are for those who want to purchase the best environmental products available on the market. Among the products and services covered are thermal insulation, indoor lighting, and glazed windows, doors and skylights. But green procurement is treated as an option rather than an obligation under current EU financial law.

The Green Building Programme (GBP) was launched by the Commission’s Joint Research Centre in 2005. The voluntary programme is to encourage owners of non-residential buildings to use cost-effective energy efficiency measures in their buildings. A GBP partner must make sure any new building consumes 25 percent less total primary energy than the existing building standard. And any existing buildings should consume at least a quarter less energy after refurbishment. “None of the audited EU institutions had adhered to the approach promoted under the GPP toolkit and the GBP for building projects in Brussels,” the auditors said. The Council told auditors the GBP was not relevant for its Europa Building (top), which is currently under construction.

Major parts of the building which have to be integrated in the project were built between 1922 and 1927 and are listed. According to the Council, this was an important technical constraint with a considerable impact on the building’s energy performance.The Commission expects to have replaced or renovated 50 percent of its total surface area in Brussels by 2025. In the coming years, the Parliament will need to renovate its main buildings in Brussels. The first to be renovated will be the Paul Henri Spaak building (left).

Major parts of the building which have to be integrated in the project were built between 1922 and 1927 and are listed. According to the Council, this was an important technical constraint with a considerable impact on the building’s energy performance.The Commission expects to have replaced or renovated 50 percent of its total surface area in Brussels by 2025. In the coming years, the Parliament will need to renovate its main buildings in Brussels. The first to be renovated will be the Paul Henri Spaak building (left).

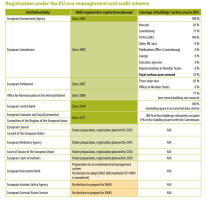

The European eco-Management and Audit Scheme (EMAS) is a programme developed by the Commission for companies to evaluate report and improve their environmental performance, including that of their buildings. Currently, more than 4,500 organisations and approximately 8,150 sites are EMAS registered worldwide. But progress in introducing it to the European institutions has been slow, the report said. EMAS registration for public administrations has been possible since 2001 and, in June 2014, seven of the audited EU institutions and bodies were registered.

EMAS at the Commission had significant limitations in scope, the auditors said. All EU institutions and bodies should sign up with EMAS and implement it, while reducing any limitations to its scope, it recommended. The EU Office for Harmonisation in the Internal Market assessed the financial benefits of its EMAS?driven investments aimed at increasing the energy efficiency of its building.

EMAS at the Commission had significant limitations in scope, the auditors said. All EU institutions and bodies should sign up with EMAS and implement it, while reducing any limitations to its scope, it recommended. The EU Office for Harmonisation in the Internal Market assessed the financial benefits of its EMAS?driven investments aimed at increasing the energy efficiency of its building.

These investments included solar panels, interior renovation and a cooling plant between 2010-2012. The Office expects to save about €2.5 million, with the return on the investment, the costs savings, due in about seven years.

In June, the Commission, in partnership with Renovate Europe and Energy Cities, displayed a giant poster on the side of its Charlemagne building, highlighting the energy consumption of Commission buildings. The EU’s Energy Efficiency Directive (2012/27/EU) requires member states to renovate 3 percent every year of their buildings owned and occupied by the central governments. The Commission has committed itself to reach the same result.That commitment could not be taken into account by auditors.

“The average energy consumption per square meter for the Commission buildings in Brussels has decreased by more than 30 percent between 2005 and 2013, which is more than 4 percent per year, and that is just the beginning!” said Marc Seguinot, Head of Unit in the OIB, responsible for the management of the Commission’s buildings. “Such significant results have encouraged us to go further, and we have planned for major renovation of Commission buildings from 2019.”