At this time of year, it seems like we don’t have to wait more than a few hours before some or other organisation is sharing its prognosis about how we will be working in the future. The thing these reports usually share in common, other than a standardised variant of a title and a common lexicon of agility, engagement and connectivity, is a narrow focus based on their key assumptions about what the office of the future will be like. While these are rarely false per se, and often offer valuable insights, they also frequently exhibit a desire to look at only one part of the great workplace elephant. While the more informed reports make excellent points and identify trends, across most there are routine flaws in thinking that can lead them to make narrow and sometimes incorrect assumptions and so draw similarly flawed conclusions. Talk of the office of the future tells us rather a lot about how we view offices right now.

At this time of year, it seems like we don’t have to wait more than a few hours before some or other organisation is sharing its prognosis about how we will be working in the future. The thing these reports usually share in common, other than a standardised variant of a title and a common lexicon of agility, engagement and connectivity, is a narrow focus based on their key assumptions about what the office of the future will be like. While these are rarely false per se, and often offer valuable insights, they also frequently exhibit a desire to look at only one part of the great workplace elephant. While the more informed reports make excellent points and identify trends, across most there are routine flaws in thinking that can lead them to make narrow and sometimes incorrect assumptions and so draw similarly flawed conclusions. Talk of the office of the future tells us rather a lot about how we view offices right now.

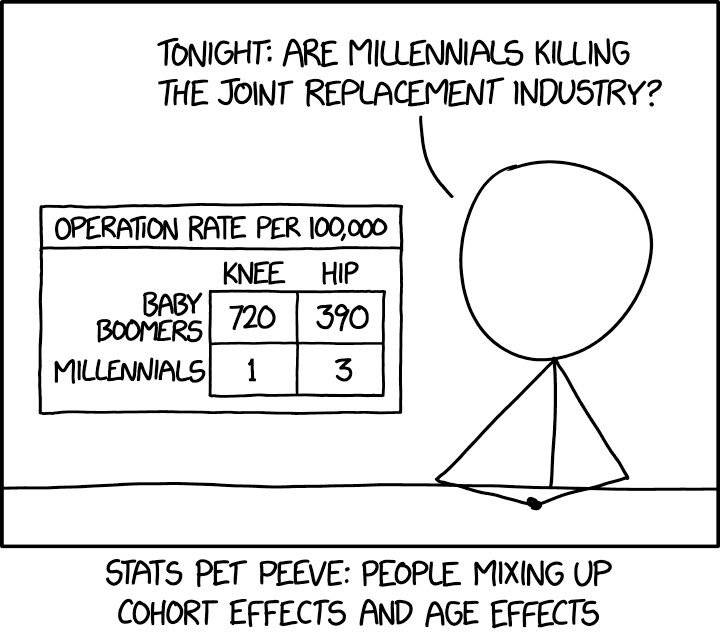

They place undue focus on Millennials. While it’s understandable that we should be interested in the influence of the newest generation of people on the way we work, not least because of their lifelong technological immersion, it’s worth noting that Millennials and now post-Millennials will still be a minority of the workforce in 2020. As this piece in Quartz highlights, the future of work will not be shaped primarily by so-called digital natives, but by a diverse and ageing workplace population. The near future will also help us to distinguish better between the characteristics of Millennials and the effects of their life stage, an issue satirised excellently by Owen Ferguson in this Tweet.

They place undue focus on Millennials. While it’s understandable that we should be interested in the influence of the newest generation of people on the way we work, not least because of their lifelong technological immersion, it’s worth noting that Millennials and now post-Millennials will still be a minority of the workforce in 2020. As this piece in Quartz highlights, the future of work will not be shaped primarily by so-called digital natives, but by a diverse and ageing workplace population. The near future will also help us to distinguish better between the characteristics of Millennials and the effects of their life stage, an issue satirised excellently by Owen Ferguson in this Tweet.

They like gimmicky designs. When these reports depict the office of the future there is a perhaps understandable tendency to focus on design quirks such as slides (such as at Ticketmaster London, pictured), isolation pods, juvenilia and free beer. It’s misguided to suggest anything other than these are appropriate features for only certain types of firms and employees. Even in those, it’s likely that some people will react against the idea of corporate prescribed fun or whatever else they claim to represent.

In some extreme cases, the supposed office of the future ignores people and their needs completely. The pathologisation of sitting that has been one of the sector’s core preoccupations over the last two or three years is now manifesting in the idea that we can do away with desks as well as chairs.

In some extreme cases, the supposed office of the future ignores people and their needs completely. The pathologisation of sitting that has been one of the sector’s core preoccupations over the last two or three years is now manifesting in the idea that we can do away with desks as well as chairs.

I can only suggest they do away with sitting for eight hour stretches in their homes and let us all know how that goes. The reality is that for the majority of people, the office of the future will be a sober and nuanced evolution of the office of the present. That is likely to include blue carpets and grey worksurfaces and a definition of cool that extends no further than the Egg chairs in reception. And there’s nothing wrong with that, or indeed anything, in the right place.

They ignore the complexities of behaviour and motivation. Too much emphasis is placed on design as a way of changing behaviour. People are motivated by a range of factors, many of them outside the control of the organisation, never mind the design of the workplace. The now routinely trotted out idea that the organisation can influence emotion and wellbeing simply by designing the workplace in a particular way is entirely dependent on the idea that an individual works in a bubble. Design becomes the major determining influence on behaviour when all other things are equal. And they never are.

The one point about office design that never gets said enough is that people can be happy, well and productive in poorly designed offices and miserable, sick and indolent in well designed space. We’ve known this for decades and yet still are told that office design and certain features produce certain outcomes. It doesn’t mean we should put people in bad offices, just that we should be aware things are complicated.

They fail to distinguish between what technology can do and what people want it to do. There is an enduring assumption that just because a technology exists people will use it and will use it in the way intended. This is so obviously not the case, we must wonder why the assumption endures. Many of these reports fall into the same trap of ignoring the unpredictable outcome once a human being gets involved. Similarly, there is an ongoing and hastening problem with the pervasive influence of technology which means that many people are essentially working for all of their waking hours because technology rarely saves our time, but distorts it.

Getting off social media may not be an option in the way Jaron Lanier suggests, but we should at least be aware of how tech is never quite what we think it is.

[embedyt] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kc_Jq42Og7Q[/embedyt]

They subvert language. The Newspeak of modern management is evident in the partial inversion of supposedly positive terms such as empowerment, agility and collaboration. Technology does not only empower people, it enslaves them, especially when firms start measuring them on their social media profile. Agile working means giving people flexibility, as well as extending the workplace beyond the walls of the office and so making their lives more rigid. Collaboration means not only sharing ideas but also ensuring that knowledge workers don’t withhold their intellectual capital or, worse, take it somewhere else, when it is the only thing most of them have to sell to employers in the first place.

They ignore the influence of the present. When George Orwell wrote 1984, the story goes that its title was derived by inverting the numbers of the year in which it was written – 1948. Whatever the truth of this tale, Orwell understood his book was as much about the world in which he lived as the one to come. Our images of the future are invariably refracted through the prism of the present. Predictions must accommodate this distortion to some degree.

They focus too much on youthful extroverts. The tenets espoused in many of these reports place too much emphasis on extroverts in the workplace. This is evident not only in the provision of quirky design features such as slides – which even many introverted Millennials wouldn’t be comfortable with never mind 50 year old accountants – but also in more generally acceptable and widespread facets of office design such as the open plan.

There are signs of a backlash to the undue focus on design based primarily on the needs of young extroverts but many of these reports continue to promote values that ignore the needs of nearly half of the population. It’s worth reminding ourselves that this would include archetypal introverts such as Warren Buffett, Charles Darwin, J.K. Rowling, Albert Einstein and Mahatma Gandhi, all of whom preferred or prefer less stimulating environments, more quiet concentration and more listening than talking.

There are signs of a backlash to the undue focus on design based primarily on the needs of young extroverts but many of these reports continue to promote values that ignore the needs of nearly half of the population. It’s worth reminding ourselves that this would include archetypal introverts such as Warren Buffett, Charles Darwin, J.K. Rowling, Albert Einstein and Mahatma Gandhi, all of whom preferred or prefer less stimulating environments, more quiet concentration and more listening than talking.

December 7, 2018

Seven reasons why this will not be the office of the future

by Mark Eltringham • Comment, Facilities management, Furniture, Workplace design

They like gimmicky designs. When these reports depict the office of the future there is a perhaps understandable tendency to focus on design quirks such as slides (such as at Ticketmaster London, pictured), isolation pods, juvenilia and free beer. It’s misguided to suggest anything other than these are appropriate features for only certain types of firms and employees. Even in those, it’s likely that some people will react against the idea of corporate prescribed fun or whatever else they claim to represent.

I can only suggest they do away with sitting for eight hour stretches in their homes and let us all know how that goes. The reality is that for the majority of people, the office of the future will be a sober and nuanced evolution of the office of the present. That is likely to include blue carpets and grey worksurfaces and a definition of cool that extends no further than the Egg chairs in reception. And there’s nothing wrong with that, or indeed anything, in the right place.

They ignore the complexities of behaviour and motivation. Too much emphasis is placed on design as a way of changing behaviour. People are motivated by a range of factors, many of them outside the control of the organisation, never mind the design of the workplace. The now routinely trotted out idea that the organisation can influence emotion and wellbeing simply by designing the workplace in a particular way is entirely dependent on the idea that an individual works in a bubble. Design becomes the major determining influence on behaviour when all other things are equal. And they never are.

The one point about office design that never gets said enough is that people can be happy, well and productive in poorly designed offices and miserable, sick and indolent in well designed space. We’ve known this for decades and yet still are told that office design and certain features produce certain outcomes. It doesn’t mean we should put people in bad offices, just that we should be aware things are complicated.

They fail to distinguish between what technology can do and what people want it to do. There is an enduring assumption that just because a technology exists people will use it and will use it in the way intended. This is so obviously not the case, we must wonder why the assumption endures. Many of these reports fall into the same trap of ignoring the unpredictable outcome once a human being gets involved. Similarly, there is an ongoing and hastening problem with the pervasive influence of technology which means that many people are essentially working for all of their waking hours because technology rarely saves our time, but distorts it.

Getting off social media may not be an option in the way Jaron Lanier suggests, but we should at least be aware of how tech is never quite what we think it is.

[embedyt] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kc_Jq42Og7Q[/embedyt]

They subvert language. The Newspeak of modern management is evident in the partial inversion of supposedly positive terms such as empowerment, agility and collaboration. Technology does not only empower people, it enslaves them, especially when firms start measuring them on their social media profile. Agile working means giving people flexibility, as well as extending the workplace beyond the walls of the office and so making their lives more rigid. Collaboration means not only sharing ideas but also ensuring that knowledge workers don’t withhold their intellectual capital or, worse, take it somewhere else, when it is the only thing most of them have to sell to employers in the first place.

They ignore the influence of the present. When George Orwell wrote 1984, the story goes that its title was derived by inverting the numbers of the year in which it was written – 1948. Whatever the truth of this tale, Orwell understood his book was as much about the world in which he lived as the one to come. Our images of the future are invariably refracted through the prism of the present. Predictions must accommodate this distortion to some degree.

They focus too much on youthful extroverts. The tenets espoused in many of these reports place too much emphasis on extroverts in the workplace. This is evident not only in the provision of quirky design features such as slides – which even many introverted Millennials wouldn’t be comfortable with never mind 50 year old accountants – but also in more generally acceptable and widespread facets of office design such as the open plan.