September 10, 2019

Start-ups slump as UK gears up for Brexit

The number of new start-ups in the UK fell sharply last year and established firms scaled back their growth ambitions due to Brexit uncertainty, according to new data looking at the health of the grassroots economy. The findings have emerged from the Enterprise Research Centre’s UK Local Growth Dashboard report, an annual publication that looks at a range of metrics charting the growth of small to medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), which account for 99 percent of all firms in the UK.

The number of new start-ups in the UK fell sharply last year and established firms scaled back their growth ambitions due to Brexit uncertainty, according to new data looking at the health of the grassroots economy. The findings have emerged from the Enterprise Research Centre’s UK Local Growth Dashboard report, an annual publication that looks at a range of metrics charting the growth of small to medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), which account for 99 percent of all firms in the UK.

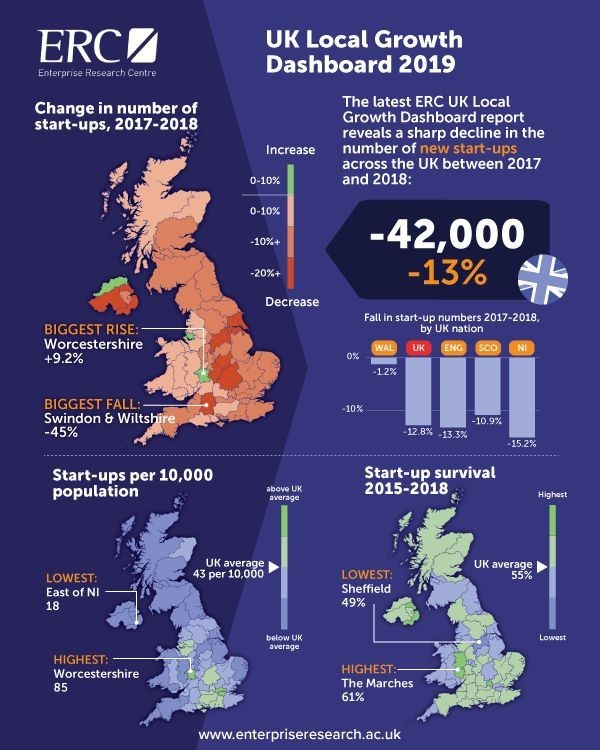

It found that in 2018 – the most recent period available in the ONS’ Business Structure Database – the number of new start-ups fell by nearly 42,000, representing a decline of 12.9 percent on the previous year for the UK as a whole (from 325,900 to 284,000).

But in some parts of the country the fall was much sharper. In Northern Ireland as a whole the figure was 15 percent lower than in 2017, the biggest drop among the UK nations. Meanwhile in England, Swindon and Wiltshire saw the biggest absolute drop with 45 percent fewer start-ups established. Just three areas saw an increase in start-ups; the North of Northern Ireland (+2.6 percent), Liverpool (+2.8 percent) and Worcestershire (+9.2 percent).

ERC researchers said the slowdown in new firm creation reflected the uncertainty around Brexit, and warned that the ongoing lack of clarity was also blunting growth ambitions in more established firms.

Other key findings from the UK Local Growth Dashboard report show that:

- A total of 284,000 new firms were started in 2018, while the three-year survival rate for start-ups stood at 55 percent. Start-up survival rates since 2015 were generally higher in the South of England and Northern Ireland, with many parts of the North of England and Midlands seeing a slight decline from the previous year.

- Among scale-ups, just 2 percent of new firms managed to grow their turnover to £1million or more within three years between 2015-18, with the highest proportion in the North of Northern Ireland (4.6 percent)

- For established firms with a turnover between £1million and £2million, 7.4 percent managed to grow above the £3million mark over three years. Again, London-based firms came top (9.5 percent), with significantly slower growth in more rural parts of England, as well as in Scotland, Northern Ireland and Wales.

- Fewer firms across the UK achieved ‘high growth’ status by growing their headcounts by an average of 10-20 percent each year for three years.

- The proportion of UK firms that succeeded in growing their productivity, with turnover increasing faster than headcount, slipped slightly to 8.3 percent in 2015-18, with Northern Ireland leading the pack (11.1 percent), followed by London, Cambridge and major city-regions in the North of England including Manchester, Leeds and Sheffield.

Warning signs

[perfectpullquote align=”right” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]It’s particularly worrying that we’re seeing an absolute decline in the number of new businesses being started in the wake of the 2016 referendum[/perfectpullquote]

Mark Hart, ERC Deputy Director and Professor of Small Business and Entrepreneurship at Aston Business School, said: “The latest Local Growth Dashboard analysis shows some clear warning signs about the health of the private sector economy in the UK. It’s particularly worrying that we’re seeing an absolute decline in the number of new businesses being started in the wake of the 2016 referendum.

“Budding entrepreneurs are clearly holding their breath waiting for some clarity about the outcome of Brexit, but if the trend continues we’ll see fewer jobs created by dynamic young firms. And while established firms are clearly still growing successfully in many parts of the country, it’s frustrating that productivity growth still seems to elude the vast majority.

“Taken together, it seems hard to avoid the conclusion that Brexit uncertainty is causing the grassroots economy to stutter. This may not yet have fed through to employment numbers, but policymakers need to be aware of the warning signs and create the certainty businesses are craving.”