May 24, 2017

Suppressed global productivity levels weigh down on personal wealth 0

The slowdown in global productivity – already underway before the last economic crisis – combined with sluggish investment, continued to undermine rises in economic output and material living standards in recent years in many of the world’s economies, according to a new report released by the OECD. In its latest Compendium of Productivity Indicators, the OECD also highlights a decoupling between productivity growth and higher real average wages in many countries, resulting in continued declines in labour’s share of national income. The report claims that the contribution of labour utilisation (hours worked per capita) to GDP growth has risen markedly in a number of countries, notably in the United Kingdom and the United States. However, rises in labour utilisation reflect two opposing effects: higher employment rates but lower average hours per worker, which points to more part-time working, often in low productivity jobs.

The slowdown in global productivity – already underway before the last economic crisis – combined with sluggish investment, continued to undermine rises in economic output and material living standards in recent years in many of the world’s economies, according to a new report released by the OECD. In its latest Compendium of Productivity Indicators, the OECD also highlights a decoupling between productivity growth and higher real average wages in many countries, resulting in continued declines in labour’s share of national income. The report claims that the contribution of labour utilisation (hours worked per capita) to GDP growth has risen markedly in a number of countries, notably in the United Kingdom and the United States. However, rises in labour utilisation reflect two opposing effects: higher employment rates but lower average hours per worker, which points to more part-time working, often in low productivity jobs.

Higher employment rates are welcome. But the fact that they, rather than increases in labour productivity, have been the most important driver of GDP per capita growth in many economies in recent years is a concern for long-term economic prospects, it adds. The OECD says productivity is ultimately a question of “working smarter” – measured by ‘multifactor’ effects – rather than “working harder”. It reflects firms’ ability to produce more output by better combining inputs through new ideas, technological innovations, as well as by way of process and organisational innovations, such as new business models.

But multi-factor growth (MFP), an important driver of labour productivity growth (measured as GDP per hour worked) in the pre-crisis period, has continued to slow in many economies, and among G7 economies, was negligible in the United Kingdom and the United States in the post-crisis period and to a lesser extent in France, as well as in Italy, where MFP growth has been negative over the last two decades. However, MFP growth has picked up in Canada, Germany and Japan.

But multi-factor growth (MFP), an important driver of labour productivity growth (measured as GDP per hour worked) in the pre-crisis period, has continued to slow in many economies, and among G7 economies, was negligible in the United Kingdom and the United States in the post-crisis period and to a lesser extent in France, as well as in Italy, where MFP growth has been negative over the last two decades. However, MFP growth has picked up in Canada, Germany and Japan.

The widespread slowdown in labour productivity growth has also been a consequence of weaker investment in machinery and equipment, which slowed across all G7 economies in the post-crisis period. Although spending by businesses on intellectual property products – particularly research and development – has been more resilient, this too has slowed from pre-crisis rates.

The weakening of growth in recent years has been spread broadly across sectors but declines have been sharpest in manufacturing, information and communication services, and in finance and insurance.

Among OECD countries, labour productivity in manufacturing slowed most markedly in recent years in the Czech Republic, Finland and Korea. In business sector services, the slowdown was most notable in Estonia, Greece, Latvia and, to a lesser extent, the United Kingdom.

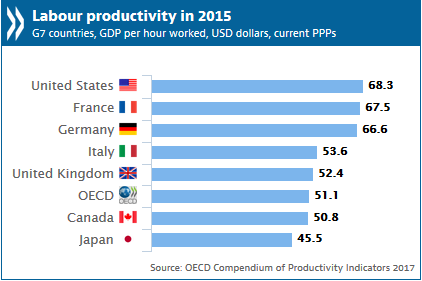

Labour productivity among the G7 countries was highest in the US where the level of GDP per hour worked was 68.3 US dollars (USD, measured at current purchasing power parities) in 2015, followed by France at 67.5 USD and Germany at 66.6 USD. Japan, at 45.5 USD, had the lowest level in the G7, below the OECD average of 51.1 USD.

In the services sector, small businesses have generally shown stronger growth than large companies since the crisis, although big firms outperformed in terms of the pace of employment growth. In manufacturing, productivity growth has been similar across small and large companies alike. The Compendium provides comparative data up to 2015 on all aspects of productivity for each OECD economy including long term productivity trends.