March 22, 2019

The future of work will be defined by four models, claims RSA

The RSA’s Future Work Centre has released research that models four ‘futures of work’ by 2035 – and claims to show how out of touch politicians are with changes in the workplace. The report, published in partnership with Arup, claims to avoid the usual sensationalism around topics such as automation, the Internet of Things, surveillance, gig work and AI to establish what workers can expect in the workplace in the near future. The report applies morphological analysis to generate its four models of work.

The RSA’s Future Work Centre has released research that models four ‘futures of work’ by 2035 – and claims to show how out of touch politicians are with changes in the workplace. The report, published in partnership with Arup, claims to avoid the usual sensationalism around topics such as automation, the Internet of Things, surveillance, gig work and AI to establish what workers can expect in the workplace in the near future. The report applies morphological analysis to generate its four models of work.

“Most of us have heard the stories: the Oxford University study that claims that 35 percent of jobs will be lost to automation, or the wild-eyed hyper-utopians who claim that a new era of bio-communism will inexorably emerge from the age of machine learning”, says Asheem Singh of the RSA. “Such visions, at times, alarm and may even excite. But they are shallow visions; invariably either focussed through the narrow lens of job losses to automation, or else speculating wildly based on precious little evidence, they offer little that is useful to the debate on the human and cultural phenomenon that is the future of work.”

- One of the major issues the report raises is the unpreparedness of politicians for the changes. Based on a YouGov study of 100 MPs, the authors claim that politicians are aware of the disruptive potential of technological change on work, but at a

- Just 15 percent of MPs think parliamentarians are doing enough to prepare workers for new technologies, while 14 percent think the same of civil servants.

- More MPs disagree than agree that they know enough about new technologies to make the right judgement calls on technology policy (43 percent to 29 percent). And this is despite 40 percent fearing the impact of technology on workers in their own constituency.

- 46 percent say dealing with tech shifts for workers will be as big a challenge as delivering Brexit.

- MPs are clueless also about the effect of radical technologies on women. They disagree that women will feel the most impact, despite emerging evidence to the contrary: three-in-ten (29 percent) Labour MPs and just 10 percent of Conservative MPs believe that women will be more affected by automation than men.

- Recent RSA research warned skilled jobs at all levels are already being ‘lost’, but unlike the loss of manufacturing and industry in the 1980s, women are currently faring worse due to automation and digital changes in banking and retail as well as public sector austerity.

- Labour MPs are more pessimistic about ‘who gains’ than Conservative MPs. Conservatives think the big winners from new tech will be consumers, but Labour MPs and the public are more sceptical: nearly half (45 percent) think consumers will be the biggest winners from technology, compared to just 12 percent of Labour, while 36 percent of Labour MPs think tech firms will gain most, with 20 percent of Conservatives agreeing, while 43 percent of Labour MPs think employers will gain the most, with just 15 percent of Conservatives agreeing.

The four models

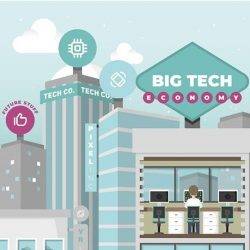

The Big Tech Economy describes a world where most technologies develop at a rapid pace, from self-driving cars to 3D printing

The Big Tech Economy describes a world where most technologies develop at a rapid pace, from self-driving cars to 3D printing

Call it Googleville or picture the Amazon rainforest being actually sponsored by Amazon. A new machine age delivers significant improvements in the quality of products and public services, with the cost of everyday goods including transport and energy plummeting. However, unemployment and economic insecurity ramp upwards, and the spoils of growth are offshored and concentrated in a handful of US and Chinese tech behemoths. The dizzying pace of change leaves workers and unions with little time to respond – and any dissent is quashed by flash PR and ‘CSR’ operations. We never stood a chance.

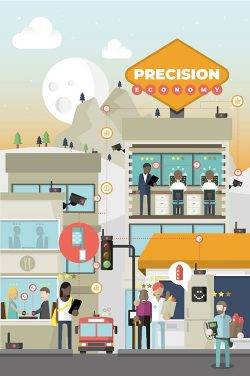

The Precision Economy portrays a future of hyper-surveillance and algorithmic optimisation

The Precision Economy portrays a future of hyper-surveillance and algorithmic optimisation

They are watching you! Here technological progress is moderate, but the juggernauts know where the value is. A proliferation of sensors allows firms to create value by capturing and analysing more information on objects, people and the environment. Gig platforms take on more prominence and rating systems become pervasive in the workplace. While some lament these trends as invasive, others believe they have ushered in a more meritocratic society where effort is more generously rewarded. A hyper-connected society also leads to wider positive spill overs, with less waste as fewer resources are left idle. And each time you recycle your personal star rating gets an additional percentile…

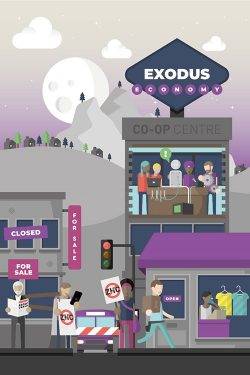

The Exodus Economy is characterised by an economic slowdown

The Exodus Economy is characterised by an economic slowdown

Get ready for the backlash. A crash on the scale of 2008 dries up funding for innovation and keeps the UK in a low-skilled, low-productivity and low-paid rut. Faced with another bout of austerity, a new generation of workers lose faith in the promise of capitalism to improve their lives, and alternative economic models gather interest. Cooperatives and mutuals emerge in large numbers to serve peoples’ core economic needs in food, energy and banking. While some workers struggle on poverty wages, others discover ways to live more self-sufficiently, including by moving away from urban areas, back to the land.

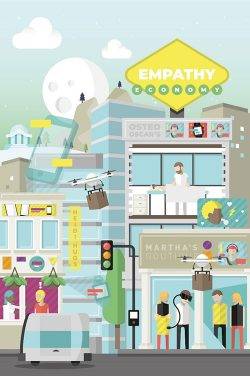

The Empathy Economy envisages a future of responsible stewardship

The Empathy Economy envisages a future of responsible stewardship

….And breathe. In this scenario, technology advances at a clip, but so too does public awareness of its dangers. Tech companies self-regulate to stem concerns and work hand in hand with external stakeholders to create new products that work on everyone’s terms. Automation, where it occurs is carefully managed in partnership with workers and unions. Disposable income flows into ‘empathy sectors’ like education, care and entertainment. This trend is broadly welcomed but brings with it a new challenge of emotional labour, where the need to be continuously expressive and available takes its toll. It’s hard being the shoulder to cry on all of the time.