In 1962, a professor of communication studies called Everett Rogers came up with the principle we call diffusion of innovation. It’s a familiar enough notion, widely taught and works by plotting the adoption of new ideas and products over time as a bell curve, before categorising groups of people along its length as innovators, early adopters, early majority, late majority, and laggards. It’s a principle bound up with human capital theory and so its influence has endured for over 50 years, albeit in a form compressed by our accelerated proliferation of ideas. It may be useful, but it lacks a third dimension in the modern era. That is, a way of describing the numbers of people who are in one category but think they are in another.

In 1962, a professor of communication studies called Everett Rogers came up with the principle we call diffusion of innovation. It’s a familiar enough notion, widely taught and works by plotting the adoption of new ideas and products over time as a bell curve, before categorising groups of people along its length as innovators, early adopters, early majority, late majority, and laggards. It’s a principle bound up with human capital theory and so its influence has endured for over 50 years, albeit in a form compressed by our accelerated proliferation of ideas. It may be useful, but it lacks a third dimension in the modern era. That is, a way of describing the numbers of people who are in one category but think they are in another.

This probably includes all of us in one way or other. This anachronism matters more and more because a growing number of ideas that are presented or perceived as new, are actually old or even outdated. Whatever the reasons for this, and the impossible task of keeping up with everything is one of the most important, we inevitably see many things as they used to be, even while our brain tells us we are looking at them as they are. We perceive aspects of the world around us as we do the lights in the night sky, a glimpse into the past, misinterpreted as the present.

All of this comes to mind as we consider ideas like the regularly reanimated corpse of telecommuting but it’s true of many related narratives about the future of work, the office of the future, new ways of working, flexible working and agile working. Call them what you like. Such ideas have been around for a very long time, even if some organisations and individuals don’t understand that or ignore it or are unaware of changes in vocabulary and thinking that accompany them. Working from home might just be work to some people, but to others it’s something they talk about as if they are the first to think of it.

All of this comes to mind as we consider ideas like the regularly reanimated corpse of telecommuting but it’s true of many related narratives about the future of work, the office of the future, new ways of working, flexible working and agile working. Call them what you like. Such ideas have been around for a very long time, even if some organisations and individuals don’t understand that or ignore it or are unaware of changes in vocabulary and thinking that accompany them. Working from home might just be work to some people, but to others it’s something they talk about as if they are the first to think of it.

A superstate of futuristic and quaint

Because of this wormhole in the diffusion of innovation curve, many of the narratives we associate with these topics exist in a quantum superstate of futuristic and quaint. For those of us close to the subject, terminology like hot desking, telework and – yes – home working are at least in some part anachronistic because they just describe work as it has been for years, and for a growing number of people.

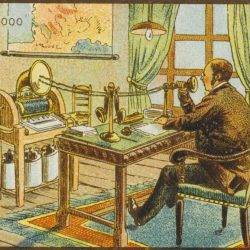

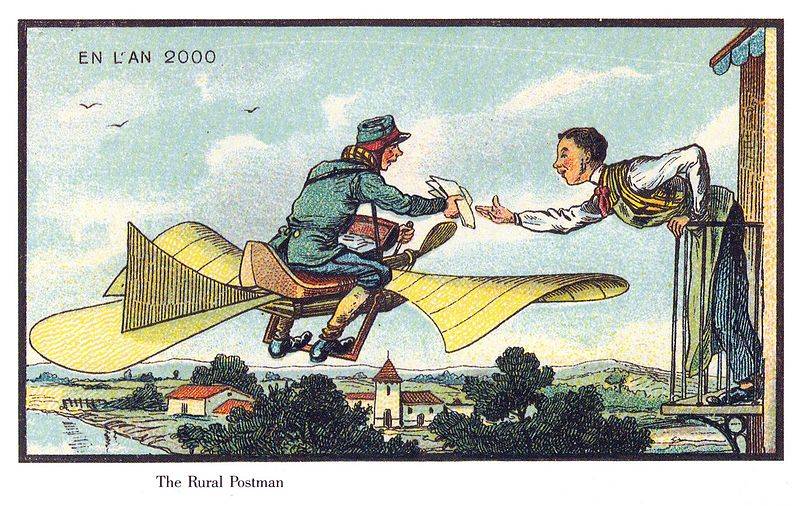

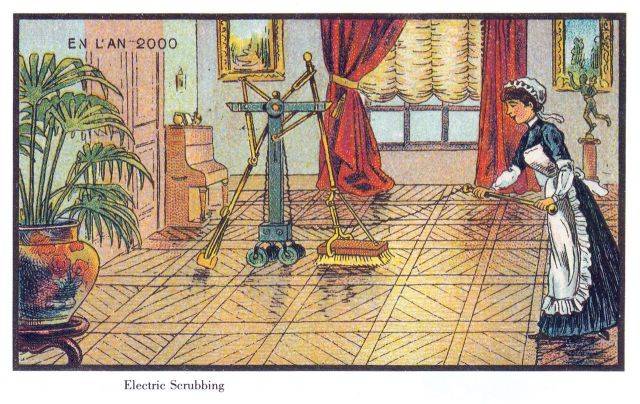

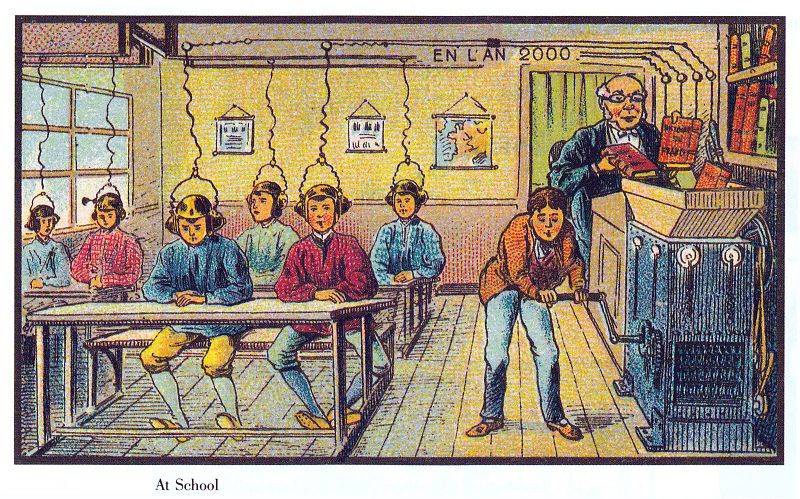

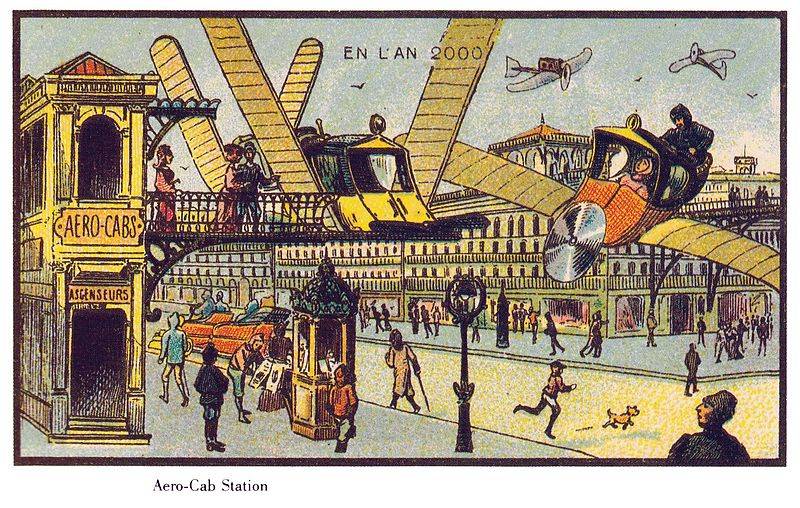

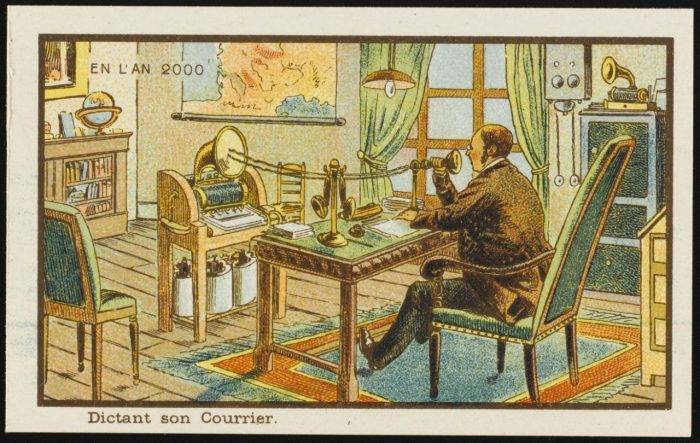

We sometimes wince at their use, especially when picked up on by the mainstream media as evidence of some false notion of the office of the future. They are steampunk terms, a blend of the advanced and archaic, as much a guide to the future as were the postcards depicting the year 2000 created by French artist Jean Marc Cote in the late 19th Century and curated by Isaac Asimov in his 1986 book Futuredays.

We sometimes wince at their use, especially when picked up on by the mainstream media as evidence of some false notion of the office of the future. They are steampunk terms, a blend of the advanced and archaic, as much a guide to the future as were the postcards depicting the year 2000 created by French artist Jean Marc Cote in the late 19th Century and curated by Isaac Asimov in his 1986 book Futuredays.

Underlying this false narrative is the very idea of the future of work. For the most part, when people use that expression they are either describing something that is already happening, should be happening more or some trite design feature that claims to be cool or quirky, but is already beyond cliché. Plonking a Mini Cooper or a pool table in an open plan office is not the future of work. It’s a distraction. If it’s not in line with the culture of the organisation, it’s like getting down with the kids. It’s a wacky tie.

There is also a misplaced linearity in this narrative. Working from home is still something that is sanctioned by the organisation. It is often seen as a treat or a benefit. It may not necessarily reflect command and control management, but it has a common ancestor with it as do many of the variants we ascribe to the concept of agile working and coworking. It is still all about time and space when it should really be about behaviour, as argued here by Neil Usher in typically masterful style.

There is also a misplaced linearity in this narrative. Working from home is still something that is sanctioned by the organisation. It is often seen as a treat or a benefit. It may not necessarily reflect command and control management, but it has a common ancestor with it as do many of the variants we ascribe to the concept of agile working and coworking. It is still all about time and space when it should really be about behaviour, as argued here by Neil Usher in typically masterful style.

The adoption of certain workplace models is based on an assumption that they are developments of the existing order. Yet we are no longer faced with an era of linear change, but one in which a number of technological forces coalesce to create a perfect storm of uncertainty. For each of these, there has yet to emerge a consensus about the nature of the technology itself and its implications for the world, so the idea we can predict with any certainty what will happen is fanciful.

In a recent presentation and blog, Antony Slumbers identified the technological trends that will drive change in the near future as well as some of the issues that will arise for workers and the people charged with creating the digital and physical spaces in which they work. This too is ultimately about behaviour and his conclusion that real estate will become about providing a service rather than a building confirms it.

In a recent presentation and blog, Antony Slumbers identified the technological trends that will drive change in the near future as well as some of the issues that will arise for workers and the people charged with creating the digital and physical spaces in which they work. This too is ultimately about behaviour and his conclusion that real estate will become about providing a service rather than a building confirms it.

This is the true future of work. Yet there is little doubt that the mainstream narrative, at least for now, will remain based on some quaint futurology. We are all ignorant in some way of our actual categorisation on the diffusion of innovation curves for specific new ideas. But when it comes to issues like working from home and the future of work, we should point out to some of those who claim to be innovators, that they might well be at the other end of the curve.

May 16, 2019

Working from home and the future of work. How quaint 0

by Mark Eltringham • Comment, Flexible working, Property, Technology

This probably includes all of us in one way or other. This anachronism matters more and more because a growing number of ideas that are presented or perceived as new, are actually old or even outdated. Whatever the reasons for this, and the impossible task of keeping up with everything is one of the most important, we inevitably see many things as they used to be, even while our brain tells us we are looking at them as they are. We perceive aspects of the world around us as we do the lights in the night sky, a glimpse into the past, misinterpreted as the present.

A superstate of futuristic and quaint

Because of this wormhole in the diffusion of innovation curve, many of the narratives we associate with these topics exist in a quantum superstate of futuristic and quaint. For those of us close to the subject, terminology like hot desking, telework and – yes – home working are at least in some part anachronistic because they just describe work as it has been for years, and for a growing number of people.

Underlying this false narrative is the very idea of the future of work. For the most part, when people use that expression they are either describing something that is already happening, should be happening more or some trite design feature that claims to be cool or quirky, but is already beyond cliché. Plonking a Mini Cooper or a pool table in an open plan office is not the future of work. It’s a distraction. If it’s not in line with the culture of the organisation, it’s like getting down with the kids. It’s a wacky tie.

The adoption of certain workplace models is based on an assumption that they are developments of the existing order. Yet we are no longer faced with an era of linear change, but one in which a number of technological forces coalesce to create a perfect storm of uncertainty. For each of these, there has yet to emerge a consensus about the nature of the technology itself and its implications for the world, so the idea we can predict with any certainty what will happen is fanciful.

This is the true future of work. Yet there is little doubt that the mainstream narrative, at least for now, will remain based on some quaint futurology. We are all ignorant in some way of our actual categorisation on the diffusion of innovation curves for specific new ideas. But when it comes to issues like working from home and the future of work, we should point out to some of those who claim to be innovators, that they might well be at the other end of the curve.