Predicting the future is a fool’s errand. History is littered with examples of people who got it horribly wrong. In 1876, William Orten, the president of then telegraphy pioneer Western Union, claimed that the telephone was an idiotic, ungainly and impractical idea that would never catch on. Almost a century later, Microsoft’s Bill Gates said that nobody would ever need more than 640KB of memory in a computer. Today’s home computers and laptops can store up to 32GB of memory.

Predicting the future is a fool’s errand. History is littered with examples of people who got it horribly wrong. In 1876, William Orten, the president of then telegraphy pioneer Western Union, claimed that the telephone was an idiotic, ungainly and impractical idea that would never catch on. Almost a century later, Microsoft’s Bill Gates said that nobody would ever need more than 640KB of memory in a computer. Today’s home computers and laptops can store up to 32GB of memory.

Sometimes futurists get it spot on, but even a stopped clock is right twice a day. Scientist and author of I, Robot Isaac Asimov, claimed that mobile computerised objects would become commonplace in the home and robotics would kill assembly-line jobs – two predictions that feel scarily prescient. Then again, Asimov also predicted that humans would be living on the moon by now.

One reason for this is that humans are poor at judging exponential scale. Especially these days, the data that underpins new technologies is almost impossible to comprehend in any practical sense. Another factor, and perhaps more relevant to our current moment, is that we tend to predict the future by extrapolating from the present. In other words, we can only conceptualise the future through the lens of our existing experiences, knowledge and biases.

‘The office is always out of date’

So, why does our inability to predict the future accurately matter so much right now? The pandemic opened the door to a new generation of fortune-tellers, sure of their answers and of the future. Many have argued that the recent mass switch to home working represents the final nail in the coffin for offices and the cities that house them. Some of the more outlandish predictions include a considerable growth in demand for holograms.

But, in truth, there is a great deal of uncertainty at the moment because nobody really knows how the post-pandemic workplace will take shape. We have no frame of reference for this unprecedented global catastrophe. If this recent period was a mass home working experiment, it was undertaken in prejudiced conditions. Nothing about the last 17 months has been flexible or hybrid.

As this site’s editor, Mark Eltringham, wrote in Creating the Productive Workplace and repeats here, many future office predictions also suppose that “just around the corner there is an idealised end point for office design” but “what this fails to account for is that the office is always out of date and always in a state of transition”.

The data to back it up

There are plenty of lessons here for those who are now planning their post-pandemic workplace strategy. Whether they’re thinking about rubber-stamping a home working model, giving employees more control over where they choose to work or redesigning the workplace to support specific work activities, the first is to eschew the headlines, biases and half-truths.

[perfectpullquote align=”right” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]Whatever new workplace model organisations introduce must be in beta[/perfectpullquote]

The second lesson is to ensure that whatever new workplace model organisations introduce is in beta. We must be prepared for a period of trial and error as they learn more about how their employees’ expectations have changed, what they want from the workspace, and where they work.

That’s where workplace data comes in. Firstly, organisations will need to know the capacity of their workplace and its constituent parts, including workstations (either fixed or flexible), meeting rooms, social spaces and more. Then, occupancy and space usage data can help organisations identify when and how often people use these areas, allowing them to create environments and flexible working policies that support their employees’ needs and help boost their productivity.

In addition, real-time occupancy data produced by smart building sensors and analytics can help workplace managers make decisions on the fly, such as reconfiguring space, a particularly useful skill when the workplace is in beta and an organisation needs to react and adapt to change quickly.

This kind of data can also support the creation of employee personas that categorise those who use the office environment by their workplace preferences, needs and challenges, allowing those responsible for managing the workplace to create bespoke user journeys and spaces for specific activities.

Recently, some high-profile companies, including Apple, Amazon and McDonald’s, have made the headlines for telling their employees to return to the office for a minimum of three days a week moving forward. But this will only work in beta. Setting a standard number of office days for the long term without the accurate, comprehensive data on how employees use the post-pandemic space is likely to turn into another doomed prediction of the future.

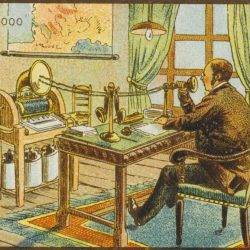

Image: A depiction of the year 2000 created by French artist Jean Marc Cote as one of a series of postcards in the late 19th Century and curated by Isaac Asimov in his 1986 book Futuredays.

November 19, 2021

Workplace data proves that the devil is in the detail for the new era of work

by Steve Morren • Comment, Flexible working, Technology, Workplace design

Sometimes futurists get it spot on, but even a stopped clock is right twice a day. Scientist and author of I, Robot Isaac Asimov, claimed that mobile computerised objects would become commonplace in the home and robotics would kill assembly-line jobs – two predictions that feel scarily prescient. Then again, Asimov also predicted that humans would be living on the moon by now.

One reason for this is that humans are poor at judging exponential scale. Especially these days, the data that underpins new technologies is almost impossible to comprehend in any practical sense. Another factor, and perhaps more relevant to our current moment, is that we tend to predict the future by extrapolating from the present. In other words, we can only conceptualise the future through the lens of our existing experiences, knowledge and biases.

‘The office is always out of date’

So, why does our inability to predict the future accurately matter so much right now? The pandemic opened the door to a new generation of fortune-tellers, sure of their answers and of the future. Many have argued that the recent mass switch to home working represents the final nail in the coffin for offices and the cities that house them. Some of the more outlandish predictions include a considerable growth in demand for holograms.

But, in truth, there is a great deal of uncertainty at the moment because nobody really knows how the post-pandemic workplace will take shape. We have no frame of reference for this unprecedented global catastrophe. If this recent period was a mass home working experiment, it was undertaken in prejudiced conditions. Nothing about the last 17 months has been flexible or hybrid.

As this site’s editor, Mark Eltringham, wrote in Creating the Productive Workplace and repeats here, many future office predictions also suppose that “just around the corner there is an idealised end point for office design” but “what this fails to account for is that the office is always out of date and always in a state of transition”.

The data to back it up

There are plenty of lessons here for those who are now planning their post-pandemic workplace strategy. Whether they’re thinking about rubber-stamping a home working model, giving employees more control over where they choose to work or redesigning the workplace to support specific work activities, the first is to eschew the headlines, biases and half-truths.

[perfectpullquote align=”right” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]Whatever new workplace model organisations introduce must be in beta[/perfectpullquote]

The second lesson is to ensure that whatever new workplace model organisations introduce is in beta. We must be prepared for a period of trial and error as they learn more about how their employees’ expectations have changed, what they want from the workspace, and where they work.

That’s where workplace data comes in. Firstly, organisations will need to know the capacity of their workplace and its constituent parts, including workstations (either fixed or flexible), meeting rooms, social spaces and more. Then, occupancy and space usage data can help organisations identify when and how often people use these areas, allowing them to create environments and flexible working policies that support their employees’ needs and help boost their productivity.

In addition, real-time occupancy data produced by smart building sensors and analytics can help workplace managers make decisions on the fly, such as reconfiguring space, a particularly useful skill when the workplace is in beta and an organisation needs to react and adapt to change quickly.

This kind of data can also support the creation of employee personas that categorise those who use the office environment by their workplace preferences, needs and challenges, allowing those responsible for managing the workplace to create bespoke user journeys and spaces for specific activities.

Recently, some high-profile companies, including Apple, Amazon and McDonald’s, have made the headlines for telling their employees to return to the office for a minimum of three days a week moving forward. But this will only work in beta. Setting a standard number of office days for the long term without the accurate, comprehensive data on how employees use the post-pandemic space is likely to turn into another doomed prediction of the future.

Steve Morren, is EMEA channel director, iOFFICE + SpaceIQ

Image: A depiction of the year 2000 created by French artist Jean Marc Cote as one of a series of postcards in the late 19th Century and curated by Isaac Asimov in his 1986 book Futuredays.