A recent edition of Jon Connell’s daily newsletter The Knowledge included this nugget: “Last month, I heard one of the world’s most successful fund managers admit that the charts and models he previously used “gave almost no clue” as to what to do with money now. (His one firm prediction, that the US dollar would weaken, has so far proved dead wrong.) Same with climate, with migration, with a business world about to be utterly transformed by AI. That, as much anything, will be one of the biggest questions of the coming years and decades: What do we do if we can’t predict the future?”

A recent edition of Jon Connell’s daily newsletter The Knowledge included this nugget: “Last month, I heard one of the world’s most successful fund managers admit that the charts and models he previously used “gave almost no clue” as to what to do with money now. (His one firm prediction, that the US dollar would weaken, has so far proved dead wrong.) Same with climate, with migration, with a business world about to be utterly transformed by AI. That, as much anything, will be one of the biggest questions of the coming years and decades: What do we do if we can’t predict the future?”

Dror Poleg explores some aspects of this here. “We live in a non-linear economy where the relationship between input and output is increasingly unclear,” he writes. “Nobody knows what’s going on because there’s simply no way to know. No one is in charge because there is nothing to be in charge of.”

The sometimes trite response to this unknowability has always been to declare that if we can’t predict the future, we should at least prepare for it. But, given the array of volatile challenges we now face, there is another question we must ask. What do we do if we can’t prepare for the future either?

[perfectpullquote align=”right” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]What lies ahead is a maze with numerous exits, not two roads diverging in a wood[/perfectpullquote]

This is a theme I’ve heard in conversation many times over the past three years as firms try to look ahead by developing a new workplace strategy, while acknowledging that there is no real way of knowing whether they are doing the right things. Yet they work in the hope that it is the best response right now and can be adapted later when more is known.

So too the uncertainty facing the brightest of their generation who dreamed of a job with the FAANG group of tech titans, only to find that their skills are unneeded in the face of mass layoffs. Even these would-be Masters of the Universe must live in hope that they can adapt. And, as Charles Handy would tell them, prepare to adapt again and again.

Even the ‘trends’ with which we are presented are no longer of any use in making sense of the future. One of the characteristics of the post-pandemic conversation about work was the proliferation of diaphanous workplace trends, few of which lasted longer than a mayfly. And the ones that did, such as The Great Resignation, don’t hold up well to scrutiny.

We should be sceptical of the trends with which we are presented by people with a vested interest in them. We should perhaps ignore them completely. Even the head of foresight at Reddit has conceded that the conflation of what is an actual trend with what is trending has unmoored us.

Which is why we should take this kind of certainty about the future of AI with a pinch of salt.

As Freddie de Boer argues here, we should be extremely suspicious about these kinds of predictions, regardless of whether they propose the now standard options of an apocalyptic or utopian future.

“This period of AI hype is among the most intellectually irresponsible and wildly conformist that I’ve ever seen. The stakes are low compared to past media failures, but I can’t remember a moment or story in which the same fundamental failures of common sense and humility were quite so universal. The sheer hubris….”

We should ignore those who present us with only two choices on complex issues. What lies ahead is a maze with numerous exits, not two roads diverging in a wood.

So, the alternative to fully remote work is not everybody back to the office five days a week, and vice versa. Proponents on both sides of this phoney war rely on the same fallacies. Firstly, that a sample size of one (them or their business, usually) has anything that can be generalised on a particular topic. The second that anybody who disagrees in the slightest must be advocating for the diametric opposite of what they are propounding.

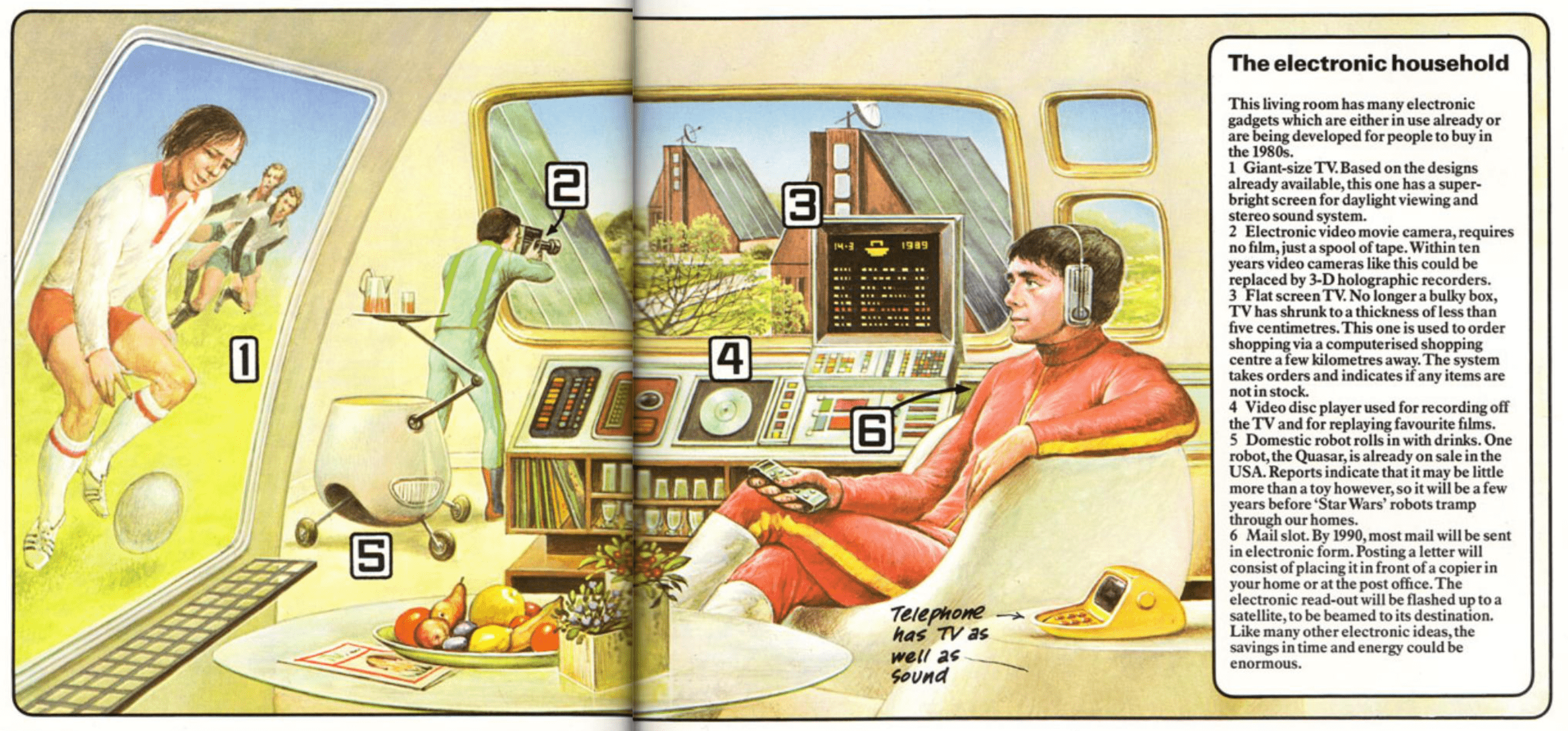

From The Usborne Book of the Future

A better future

I recently received a copy of the reissued Usborne Book of the Future. Originally published in 1979, the book explores what life will be like in the 21st Century. It’s got all the stuff you would expect, but what is particularly striking is how optimistic it was. The future used to be glorious. And this optimism was evident in the artwork, layout and typography as well as the copy.

It is a marked contrast to the widespread feelings of confused helplessness we have in the face of war, climate change, technological upheaval, social change and economic uncertainty. But maybe that is because of the mechanisms which provide us with information. Maybe we are looking at it all wrong.

I bring this up because the answer to the question posited in the first paragraph lies, literally, in Pandora’s Box. According to Hesiod’s version of the myth, when Prometheus stole fire from heaven, Zeus took vengeance by presenting Pandora to Prometheus’ brother Epimetheus. Pandora opened a container left in her care releasing a number of great troubles into the world, including Death. As she hurried to close the container, one thing was left behind – Hope.

We may not be in control of what the future holds or able to predict it, but we should rediscover the hope that it will be better.

Some things I liked this week

Small acts of kindness are frequent and universal

Why Gen Z is ditching smartphones for dumb phones

This refrigerator from 1956 has more features than modern day fridges

The technological view of the world of Martin Heidegger

The nightmare that is a reality

How to take better breaks at work, according to research

Is it a bus? Is it a plane? No, it’s your workplace

Main image: From Dante Gabriel Rossetti‘s painting of Pandora holding the box, 1871

Mark is the publisher of Workplace Insight, IN magazine, Works magazine and is the European Director of Work&Place journal. He has worked in the office design and management sector for over thirty years as a journalist, marketing professional, editor and consultant.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=atuK5n-R8nw

June 9, 2023

Getting back to the idea of a better future

by Mark Eltringham • Comment, Technology

Dror Poleg explores some aspects of this here. “We live in a non-linear economy where the relationship between input and output is increasingly unclear,” he writes. “Nobody knows what’s going on because there’s simply no way to know. No one is in charge because there is nothing to be in charge of.”

The sometimes trite response to this unknowability has always been to declare that if we can’t predict the future, we should at least prepare for it. But, given the array of volatile challenges we now face, there is another question we must ask. What do we do if we can’t prepare for the future either?

[perfectpullquote align=”right” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]What lies ahead is a maze with numerous exits, not two roads diverging in a wood[/perfectpullquote]

This is a theme I’ve heard in conversation many times over the past three years as firms try to look ahead by developing a new workplace strategy, while acknowledging that there is no real way of knowing whether they are doing the right things. Yet they work in the hope that it is the best response right now and can be adapted later when more is known.

So too the uncertainty facing the brightest of their generation who dreamed of a job with the FAANG group of tech titans, only to find that their skills are unneeded in the face of mass layoffs. Even these would-be Masters of the Universe must live in hope that they can adapt. And, as Charles Handy would tell them, prepare to adapt again and again.

Even the ‘trends’ with which we are presented are no longer of any use in making sense of the future. One of the characteristics of the post-pandemic conversation about work was the proliferation of diaphanous workplace trends, few of which lasted longer than a mayfly. And the ones that did, such as The Great Resignation, don’t hold up well to scrutiny.

We should be sceptical of the trends with which we are presented by people with a vested interest in them. We should perhaps ignore them completely. Even the head of foresight at Reddit has conceded that the conflation of what is an actual trend with what is trending has unmoored us.

Which is why we should take this kind of certainty about the future of AI with a pinch of salt.

As Freddie de Boer argues here, we should be extremely suspicious about these kinds of predictions, regardless of whether they propose the now standard options of an apocalyptic or utopian future.

“This period of AI hype is among the most intellectually irresponsible and wildly conformist that I’ve ever seen. The stakes are low compared to past media failures, but I can’t remember a moment or story in which the same fundamental failures of common sense and humility were quite so universal. The sheer hubris….”

We should ignore those who present us with only two choices on complex issues. What lies ahead is a maze with numerous exits, not two roads diverging in a wood.

So, the alternative to fully remote work is not everybody back to the office five days a week, and vice versa. Proponents on both sides of this phoney war rely on the same fallacies. Firstly, that a sample size of one (them or their business, usually) has anything that can be generalised on a particular topic. The second that anybody who disagrees in the slightest must be advocating for the diametric opposite of what they are propounding.

From The Usborne Book of the Future

A better future

I recently received a copy of the reissued Usborne Book of the Future. Originally published in 1979, the book explores what life will be like in the 21st Century. It’s got all the stuff you would expect, but what is particularly striking is how optimistic it was. The future used to be glorious. And this optimism was evident in the artwork, layout and typography as well as the copy.

It is a marked contrast to the widespread feelings of confused helplessness we have in the face of war, climate change, technological upheaval, social change and economic uncertainty. But maybe that is because of the mechanisms which provide us with information. Maybe we are looking at it all wrong.

I bring this up because the answer to the question posited in the first paragraph lies, literally, in Pandora’s Box. According to Hesiod’s version of the myth, when Prometheus stole fire from heaven, Zeus took vengeance by presenting Pandora to Prometheus’ brother Epimetheus. Pandora opened a container left in her care releasing a number of great troubles into the world, including Death. As she hurried to close the container, one thing was left behind – Hope.

We may not be in control of what the future holds or able to predict it, but we should rediscover the hope that it will be better.

Some things I liked this week

Small acts of kindness are frequent and universal

Why Gen Z is ditching smartphones for dumb phones

This refrigerator from 1956 has more features than modern day fridges

The technological view of the world of Martin Heidegger

The nightmare that is a reality

How to take better breaks at work, according to research

Is it a bus? Is it a plane? No, it’s your workplace

Main image: From Dante Gabriel Rossetti‘s painting of Pandora holding the box, 1871

Mark is the publisher of Workplace Insight, IN magazine, Works magazine and is the European Director of Work&Place journal. He has worked in the office design and management sector for over thirty years as a journalist, marketing professional, editor and consultant.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=atuK5n-R8nw