March 11, 2019

Revisiting Maslow and the quest for self-actualisation

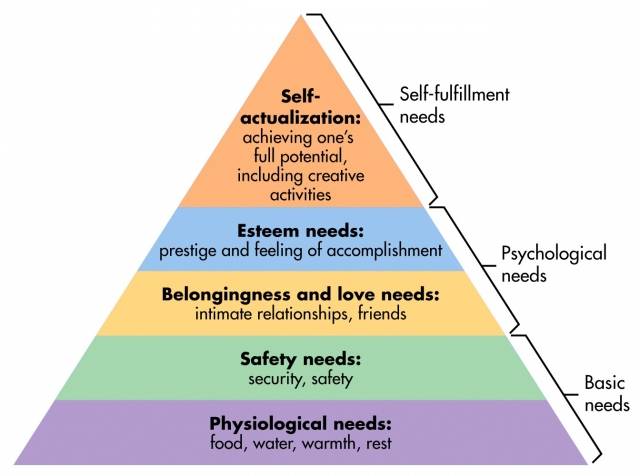

Abraham Maslow was the 20th-century American psychologist best-known for explaining motivation through his hierarchy of needs, which he represented in a pyramid. At the base, our physiological needs include food, water, warmth and rest. Moving up the ladder, Maslow mentions safety, love, and self-esteem and accomplishment. But after all those have been satisfied, the motivating factor at the top of the pyramid involves striving to achieve our full potential and satisfy creative goals. As one of the founders of humanistic psychology, Maslow proposed that the path to self-transcendence and, ultimately, greater compassion for all of humanity requires the ‘self-actualisation’ at the top of his pyramid – fulfilling your true potential, and becoming your authentic self.

Abraham Maslow was the 20th-century American psychologist best-known for explaining motivation through his hierarchy of needs, which he represented in a pyramid. At the base, our physiological needs include food, water, warmth and rest. Moving up the ladder, Maslow mentions safety, love, and self-esteem and accomplishment. But after all those have been satisfied, the motivating factor at the top of the pyramid involves striving to achieve our full potential and satisfy creative goals. As one of the founders of humanistic psychology, Maslow proposed that the path to self-transcendence and, ultimately, greater compassion for all of humanity requires the ‘self-actualisation’ at the top of his pyramid – fulfilling your true potential, and becoming your authentic self.

Now Scott Barry Kaufman, a psychologist at Barnard College, Columbia University, believes it is time to revive the concept, and link it with contemporary psychological theory. ‘We live in times of increasing divides, selfish concerns, and individualistic pursuits of power,’ Kaufman wrote recently in a blog in Scientific American introducing his new research. He hopes that rediscovering the principles of self-actualisation might be just the tonic that the modern world is crying out for. To this end, he’s used modern statistical methods to create a test of self-actualisation or, more specifically, of the 10 characteristics exhibited by self-actualised people, and it was recently published in the Journal of Humanistic Psychology.

The characteristics of self-actualisation

Kaufman first surveyed online participants using 17 characteristics Maslow believed were shared by self-actualised people. Kaufman found that seven of these were redundant or irrelevant and did not correlate with others, leaving 10 key characteristics of self-actualisation.

Next, he reworded some of Maslow’s original language and labelling to compile a modern 30-item questionnaire featuring three items tapping each of these 10 remaining characteristics: continued freshness of appreciation; acceptance; authenticity; equanimity; purpose; efficient perception of reality; humanitarianism; peak experiences; good moral intuition; and creative spirit (see the full questionnaire below, and take the test on Kaufman’s website).

So what did Kaufman report? In a survey of more than 500 people on Amazon’s Mechanical Turk website, Kaufman found that scores on each of these 10 characteristics tended to correlate, but also that they each made a unique contribution to a unifying factor of self-actualisation – suggesting that this is a valid concept comprised of ten subtraits.

Participants’ total scores on the test also correlated with their scores on the main five personality traits (that is, with higher extraversion, agreeableness, emotional stability, openness and conscientiousness) and with the metatrait of ‘stability’, indicative of an ability to avoid impulses in the pursuit of one’s goals. That the new test corresponded in this way with established personality measures provides further evidence of its validity.

Next, Kaufman turned to modern theories of wellbeing, such as self-determination theory, to see if people’s scores on his self-actualisation scale correlated with these contemporary measures. Sure enough, he found that people with more characteristics of self-actualisation also tended to score higher on curiosity, life-satisfaction, self-acceptance, personal growth and autonomy, among other factors – just as Maslow would have predicted.

Overcoming an egocentric focus

‘Taken together, this total pattern of data supports Maslow’s contention that self-actualised individuals are more motivated by growth and exploration than by fulfilling deficiencies in basic needs,’ Kaufman writes. He adds that the new empirical support for Maslow’s ideas is ‘quite remarkable’ given that Maslow put them together with ‘a paucity of actual evidence’.

A criticism often levelled at Maslow’s notion of self-actualisation is that its pursuit encourages an egocentric focus on one’s own goals and needs. However, Maslow always contended that it is only through becoming our true, authentic selves that we can transcend the self and look outward with compassion to the rest of humanity. Kaufman explored this too, and found that higher scorers on his self-actualisation scale tended also to score higher on feelings of oneness with the world, but not on decreased self-salience, a sense of independence and bias toward information relevant to oneself. (These are the two main factors in a modern measure of self-transcendence developed by the psychologist David Yaden at the University of Pennsylvania.)

A criticism often levelled at Maslow’s notion of self-actualisation is that its pursuit encourages an egocentric focus on one’s own goals and needs. However, Maslow always contended that it is only through becoming our true, authentic selves that we can transcend the self and look outward with compassion to the rest of humanity. Kaufman explored this too, and found that higher scorers on his self-actualisation scale tended also to score higher on feelings of oneness with the world, but not on decreased self-salience, a sense of independence and bias toward information relevant to oneself. (These are the two main factors in a modern measure of self-transcendence developed by the psychologist David Yaden at the University of Pennsylvania.)

Kaufman said that this last finding supports ‘Maslow’s contention that self-actualising individuals are able to paradoxically merge with a common humanity while at the same time able to maintain a strong identity and sense of self’.

Where the new data contradicts Maslow is on the demographic factors that correlate with characteristics of self-actualisation – he thought that self-actualisation was rare and almost impossible for young people. Kaufman, by contrast, found scores on his new scale to be normally distributed through his sample (that is, spread evenly like height or weight) and unrelated to factors such as age, gender and educational attainment (although, in personal correspondence, Kaufman informs me that newer data – more than 3,000 people have since taken the new test – is showing a small, but statistically significant association between older age and having more characteristics of self-actualisation).

In conclusion, Kaufman writes that: ‘[H]opefully the current study … brings Maslow’s motivational framework and the central personality characteristics described by the founding humanistic psychologists, into the 21st century.’

The new test is sure to reinvigorate Maslow’s ideas, but if this is to help heal our divided world, then the characteristics required for self-actualisation, rather than being a permanent feature of our personalities, must be something we can develop deliberately. I put this point to Kaufman and he is optimistic. ‘I think there is significant room to develop these characteristics [by changing your habits],’ he told me. ‘A good way to start with that,’ he added, ‘is by first identifying where you stand on those characteristics and assessing your weakest links. Capitalise on your highest characteristics but also don’t forget to intentionally be mindful about what might be blocking your self-actualisation … Identify your patterns and make a concerted effort to change. I do think it’s possible with conscientiousness and willpower.’

________________________________