Work-related stress is the biggest cause of working days lost in the UK. According to the HSE’s most recent statistics, around 11.3 million days were lost to it in 2013/14, the most significant cause of absenteeism. The reasons for this are clear in the minds of many: the demands made on us by employers are increasingly intolerable, our own time is being eroded by work, we spend too much time at work, we’re under excessive pressure to perform and as a result we’re all either knackered, unfulfilled, stressed, depressed or anxious. Or guzzling a noxious cocktail of all of them. But there is another factor that has come into play over the last few years. As workstation sizes have contracted in response to new technologies and new space planning models, people have been forced closer to their colleagues, meaning that not only has their time been eroded, so has their space.

Organisations are always keen to sweat their assets and buildings are no different. The universal use of flat computer screens, mobile technology and new ways of planning have meant that the density at which buildings are occupied has been rising for the past few years. Flat monitors allow furniture designers and space planners to work with rectilinear workstation footprints. The increased mobility of the workforce has placed less emphasis on personal space within the office. And the effect has been dramatic. Typically we’ve seen something like a net space saving of up to 20 per cent and 25 per cent per workstation. In some cases the very idea of owned space has been usurped by the notion that a building is a shared resource.

Now this may make good for the bottom line but without proper management it may overlook that rather less mutable element of the workplace; its people. Human beings are incredibly sensitive to pressure on their personal space. So sensitive in fact that it is possible to measure to the inch the point at which they feel it is being violated, with a bit of slack for cultural variations.

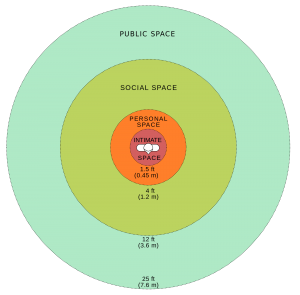

The godfather of personal space, or proxemics, is anthropologist Edward T. Hall who developed the idea in the 1950s and 1960s and laid out what he considered to be the levels at which personal space functions with four interpersonal zones.

- intimate (0 to 18 inches)

- personal (18 inches to 4 feet)

- social (4 feet to 12 feet)

- public (12 feet and beyond)

Violations of these zones are likely to provoke strong reactions in people including feelings of anger, stress and embarrassment and make communication far more difficult. The situation is complicated by different cultural attitudes.

The devil in this particular detail lies in the response people have to their environment and the people around them. The HSE’s own definition of stress sees this as a two-sided equation which takes into account both the pressure on an individual and their response to it. Much of what we currently mean by stress is determined by the individual’s response to the demands made on them by an employer. Sometimes those demands might be normal and the stress is down to the response, not the stimulus.

The devil in this particular detail lies in the response people have to their environment and the people around them. The HSE’s own definition of stress sees this as a two-sided equation which takes into account both the pressure on an individual and their response to it. Much of what we currently mean by stress is determined by the individual’s response to the demands made on them by an employer. Sometimes those demands might be normal and the stress is down to the response, not the stimulus.

However, it would be wrong to conclude that people suffering from stress just need to pull themselves together. The point about the relationship between time awareness and stress is that there are always things that make all of us feel more stressed, regardless of our personality and our relationship with whatever is causing us stress.

Design and space planning have a role to play in this but so does good management. This may include discouraging people from producing the sorts of noise that others find most annoying. The two go hand in hand so outlawing novelty ring tones can be just as important as having break-out spaces. When it comes to sound, it’s important to distinguish between types of noise and to address the layout of the office accordingly to ensure that there are minimal opportunities for people to be exposed to the kinds of sounds that distract them or drive them nuts.

And remember that some noise in an office is good. It gives an impression of busy-ness and makes people feel they belong. We’re not after barrenness, sterility and silence. Other people may drive us mad, but we’re still social creatures and isolation is far worse.

[embedplusvideo height=”252″ width=”300″ standard=”https://www.youtube.com/v/NGVSIkEi3mM?fs=1″ vars=”ytid=NGVSIkEi3mM&width=300&height=252&start=&stop=&rs=w&hd=0&autoplay=0&react=1&chapters=¬es=” id=”ep5379″ /]

August 17, 2015

What Edward T Hall (and Jerry Seinfeld) can teach us about stress and design

by Mark Eltringham • Comment, Facilities management, Workplace, Workplace design

Work-related stress is the biggest cause of working days lost in the UK. According to the HSE’s most recent statistics, around 11.3 million days were lost to it in 2013/14, the most significant cause of absenteeism. The reasons for this are clear in the minds of many: the demands made on us by employers are increasingly intolerable, our own time is being eroded by work, we spend too much time at work, we’re under excessive pressure to perform and as a result we’re all either knackered, unfulfilled, stressed, depressed or anxious. Or guzzling a noxious cocktail of all of them. But there is another factor that has come into play over the last few years. As workstation sizes have contracted in response to new technologies and new space planning models, people have been forced closer to their colleagues, meaning that not only has their time been eroded, so has their space.

Organisations are always keen to sweat their assets and buildings are no different. The universal use of flat computer screens, mobile technology and new ways of planning have meant that the density at which buildings are occupied has been rising for the past few years. Flat monitors allow furniture designers and space planners to work with rectilinear workstation footprints. The increased mobility of the workforce has placed less emphasis on personal space within the office. And the effect has been dramatic. Typically we’ve seen something like a net space saving of up to 20 per cent and 25 per cent per workstation. In some cases the very idea of owned space has been usurped by the notion that a building is a shared resource.

Now this may make good for the bottom line but without proper management it may overlook that rather less mutable element of the workplace; its people. Human beings are incredibly sensitive to pressure on their personal space. So sensitive in fact that it is possible to measure to the inch the point at which they feel it is being violated, with a bit of slack for cultural variations.

The godfather of personal space, or proxemics, is anthropologist Edward T. Hall who developed the idea in the 1950s and 1960s and laid out what he considered to be the levels at which personal space functions with four interpersonal zones.

Violations of these zones are likely to provoke strong reactions in people including feelings of anger, stress and embarrassment and make communication far more difficult. The situation is complicated by different cultural attitudes.

However, it would be wrong to conclude that people suffering from stress just need to pull themselves together. The point about the relationship between time awareness and stress is that there are always things that make all of us feel more stressed, regardless of our personality and our relationship with whatever is causing us stress.

Design and space planning have a role to play in this but so does good management. This may include discouraging people from producing the sorts of noise that others find most annoying. The two go hand in hand so outlawing novelty ring tones can be just as important as having break-out spaces. When it comes to sound, it’s important to distinguish between types of noise and to address the layout of the office accordingly to ensure that there are minimal opportunities for people to be exposed to the kinds of sounds that distract them or drive them nuts.

And remember that some noise in an office is good. It gives an impression of busy-ness and makes people feel they belong. We’re not after barrenness, sterility and silence. Other people may drive us mad, but we’re still social creatures and isolation is far worse.

[embedplusvideo height=”252″ width=”300″ standard=”https://www.youtube.com/v/NGVSIkEi3mM?fs=1″ vars=”ytid=NGVSIkEi3mM&width=300&height=252&start=&stop=&rs=w&hd=0&autoplay=0&react=1&chapters=¬es=” id=”ep5379″ /]