September 9, 2019

Aping our robot overlords, Instagrammable buildings and some other stuff

What happens to people when their skills become obsolete? If you’re not asking yourself this question already, you probably should. A new study from researchers at MIT and Wharton is the basis for this piece in Quartz at Work which considers the implications for what looks like a small technological change and its consequences for a large number of people who had to reset what they offered employers.

What happens to people when their skills become obsolete? If you’re not asking yourself this question already, you probably should. A new study from researchers at MIT and Wharton is the basis for this piece in Quartz at Work which considers the implications for what looks like a small technological change and its consequences for a large number of people who had to reset what they offered employers.

Of course the main change will not come from tweaks to the way Apple wants its browsers to work but from the advent of artificial intelligence and automation, which IBM predicts could mean the compelled reskilling of around 120 million people in the world’s largest economies over the next three years. And if anybody thinks they may swerve this force, it could be that they have made the mistake of believing that their job fits them rather than the other way around.

One of the surprising consequences of all this might be that opportunities open up for people to pretend to be robots themselves, according to this piece in the Wall Street Journal (registration) which suggests that wannabe tech disruptors are perfectly prepared to fake it till they make it.

Another unintended consequence of this new era of insecurity might be a loss of employee engagement. As Maria Gottschalk writes in the Harvard Business Review:

Most of us find it challenging to do our best work when our work environment feels unstable. For example, if you find yourself in the midst of an organizational change, your psychological resources — such as resilience and optimism — may be stretched to the limit. If the way forward at work is particularly unclear, you’ll undoubtedly devote precious energy considering not only the future of the organization, but your personal future there as well. In that context, you might think twice about a risky stretch assignment, even if it could potentially benefit your career and the organization in the long-term. This is often the case if faith in the underlying organizational foundation is acutely in question.

This is a serious problem that many organisations are going to have to have to look at in new ways, rather than relying on perks and gimmicks to address this and other issues like productivity and wellbeing. We reported last week on one aspect of this issue – how firms tend to overlook workplace basics like air quality, rest, personal control and daylight in favour of ping pong tables and nap pods and it seems like the message is finally getting across in the mainstream media.

[embedyt] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4_k8CFmmIi8[/embedyt]

Sophie Perryer makes the point in this article in World Finance, although Andrew Edgecliffe-Johnson takes a slightly different tack in the FT, acknowledging that while people do get more from firms who address bigger issues related to security and engagement, once people have their corporate gewgaws, it can be counterproductive to remove them.

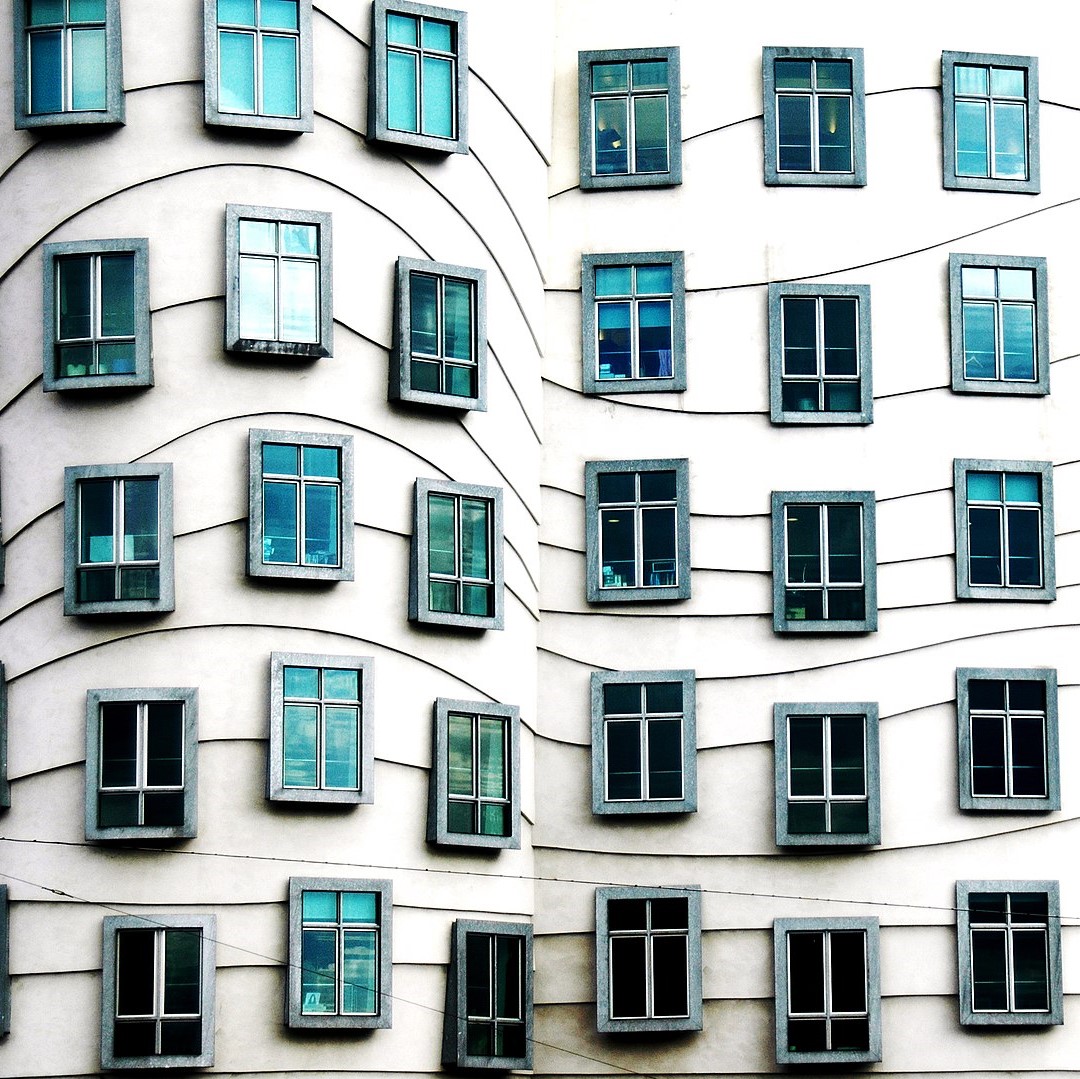

Our attraction to the frivolous and ephemeral is also the subject of this piece in Dezeen from Will Jennings, which considers how the thinking of architects may be distorted by how their creations will look on Instagram. In one way this is not a new phenomenon, because there has always a been a suspicion that architects have an eye on what their peers and the editors of the Architectural Review will make of them.

The author argues that there is a distinction between trying to please informed peers and another wondering what a tourist will make of a building and its suitability for a picture nobody may ever see.

The risk is that to create an urban form which civically and environmentally should be designed with a longview of centuries over the instant marketable moment, we are simply building for a way of being in place which will be redundant before we realise.

Maybe this is a period we will look back on with bewilderment at the idea we were designing not for the immediate user in the physical place, but for the imagined perception of that user to a hypothetical digital audience.

One other challenge for architects and their long term legacy is the subject of this piece by Lloyd Alter which questions the short life cycle of a building in New York to ponder what exactly the hell we’re playing at and what the architecture profession can do to actually live up to its own declarations about sustainability.

Building giant green office towers while knocking down slightly less giant green office towers doesn’t cut it.

Mark is the publisher of Workplace Insight, IN magazine, Works magazine and is the European Director of Work&Place journal. He has worked in the office design and management sector for over thirty years as a journalist, marketing professional, editor and consultant.