June 13, 2022

To provide people with better indoor air quality, we need a major upgrade of buildings

Government must seize the post-pandemic opportunity to mandate long-term improvements to infection control in commercial, public and residential buildings to improve indoor air quality, reduce the transmission of future waves of COVID-19, new pandemics, seasonal influenza and other infectious diseases, according to a report published by the National Engineering Policy Centre (NEPC). Infection control must also be coordinated with efforts to improve energy efficiency and fire safety, to support the three goals of safe, healthy and sustainable buildings.

Government must seize the post-pandemic opportunity to mandate long-term improvements to infection control in commercial, public and residential buildings to improve indoor air quality, reduce the transmission of future waves of COVID-19, new pandemics, seasonal influenza and other infectious diseases, according to a report published by the National Engineering Policy Centre (NEPC). Infection control must also be coordinated with efforts to improve energy efficiency and fire safety, to support the three goals of safe, healthy and sustainable buildings.

In the event of another severe pandemic during the next 60 years, the societal cost to the UK could equate to £23billion a year, according to an economic assessment that informed the report and that is thought to be the first analysis of its kind following the COVID-19 pandemic. Even without the extreme circumstances of a pandemic, the report estimates that seasonal diseases cost the country as much as £8 billion a year in disruption and sick days. Improving ventilation, air quality and sanitation in buildings could minimise transmission, reducing the number of people infected, thereby saving lives and reducing ill health and its societal impacts.

Commissioned in 2021 by the Government Chief Scientific Adviser Sir Patrick Vallance FRS FMedSci, the NEPC research, led by the Royal Academy of Engineering and the Chartered Institution of Building Services Engineers (CIBSE), set out to identify the measures needed in the UK’s built environment and transport systems to reduce transmission of infectious diseases.

[perfectpullquote align=”right” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]Many of the UK’s buildings are not being operated according to current air quality standards[/perfectpullquote]

Ensuring that buildings and transport systems are designed, operated, managed and regulated for infection control and indoor air quality is critical to minimise transmission, states the report. However, the pandemic has highlighted that many of the UK’s buildings are not being operated according to the current air quality standards, because they were built to previous standards or before standards were introduced, they have been modified over time, or are not operated as originally intended. People should be able to have confidence that the air in the buildings they use is safe to breathe, just as they would expect the water to be safe to drink.

As well as reducing the impacts of future pandemics, seasonal flu and the associated economic and social costs, the report identifies additional benefits from improving infection resilience. For example, improved ventilation has been proven to reduce infection risks, boost productivity and alleviate asthma and general exposure to air pollutants that can contribute to ‘sick building syndrome’. No-touch technologies, such as sensor-operated doors, help prevent infection on surfaces but also help support building users in wheelchairs. The report recommends that any system used within a building design should be considered from an infection perspective to identify if and where there are wider opportunities to improve experiences and duty of care for building users.

Today’s report recommends new regulations and standards that apply throughout the lifetime of a building to create healthier environments, taking lessons from existing accessibility, Legionella, or fire regulations. In addition to this, codes of practice should be introduced to make sure that the health of building occupants is a day-to-day consideration for those in the building and construction industry, from designers through to asset managers. The report makes eight recommendations to enshrine infection resilience in building regulations and improve the health of our indoor environments, which include:

- Establishing best practice – the British Standards Institution (BSI) should convene the relevant expertise and develop meaningful standards that are embedded into existing design and operational practices.

- Promoting building health – the UK Health Security Agency should promote the benefits of infection resilience and good indoor air quality to building and transport owners and the public through signage and ratings in a similar way to food or water standards.

- Ensuring that buildings operate as designed in terms of infection resilience – industry bodies and public procurement must drive improvements to the commissioning and testing of building systems at handover, and subsequently over the life of a building.

- Establishing in-use regulations with local authorities by 2030 to maintain standards of safe and healthy building performance over the building lifetime.

- Ensuring Government departments such as BEIS, DfT and DLUHC consider incorporating infection resilience into major retrofit programmes designed to meet the commitments of the Net Zero Strategy.

Professor Peter Guthrie OBE FREng, Vice President of the Royal Academy of Engineering and Chair of the NEPC Infection Resilient Environments working group, says: “If the built environment is not equipped to limit the spread of infections, there will be direct health costs from severe illness, long-term sickness or death. These will be further compounded into economic and social costs as health costs disrupt businesses, education and our daily lives.

“This is not simple because the developers who commission and fund new buildings will not directly benefit from including health provisions at the design stage. Changes to regulation and standards are therefore needed for the scale of change required. The public have a right to expect that buildings and transport will be designed and managed to control infection and minimise the impact of both seasonal diseases and future pandemics.

“With commitments to retrofitting buildings as part of the Net Zero Strategy, there is a moment now to take a coordinated approach to achieve infection resilience alongside improvements in energy efficiency and fire safety. Grasping that opportunity can help deliver a built environment that is safe, healthy and secure.”

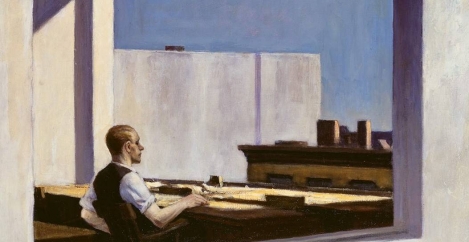

Image: From Edward Hopper’s Office in a Small City.