We know, and have for a long time, that the workplace is in a state of near constant flux and so we often fall into the trap of assuming that there is some sort of evolution towards an idealised version of it. That is why we see so many people routinely willing to suspend their critical facilities to make extravagant and even absurd predictions about the office of the future or even the death of the office. This is perniciously faulty thinking. However we can frame a number of workplace related ideas in terms of evolutionary theory, so long as we accept one of the central precepts about evolution. Namely that there is no end game, just types progressing and sometimes dying out along the distinct branches of a complex ecosystem. As a nerdy sort of guy of a certain age, I’ve tended to frame my thoughts on all of this with reference to an idea from The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy by the great Douglas Adams.

We know, and have for a long time, that the workplace is in a state of near constant flux and so we often fall into the trap of assuming that there is some sort of evolution towards an idealised version of it. That is why we see so many people routinely willing to suspend their critical facilities to make extravagant and even absurd predictions about the office of the future or even the death of the office. This is perniciously faulty thinking. However we can frame a number of workplace related ideas in terms of evolutionary theory, so long as we accept one of the central precepts about evolution. Namely that there is no end game, just types progressing and sometimes dying out along the distinct branches of a complex ecosystem. As a nerdy sort of guy of a certain age, I’ve tended to frame my thoughts on all of this with reference to an idea from The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy by the great Douglas Adams.

The Guide states that the history of every civilisation tends to pass through three distinct phases; those of survival, inquiry and sophistication. The first phase is characterised by the question ‘how can we eat?’, the second by the question ‘why do we eat?’ and the third by the question ‘where shall we have lunch?’

I think the comparison is pretty clear. At the most basic level, owning an office is largely about survival. You need to have an office because you need somewhere to work. It doesn’t really matter that much what it’s like, so long as it doesn’t cost too much and it provides a basic level of comfort and possibly a rudimentary sense of style. This sort of office is far more common than most people care to admit and its role is certainly underplayed in media coverage.

At the enquiry level, people question what they expect from their offices or even why they need an office at all. This question is not as prevalent as it once was, but even the inquiry stage continues, although it’s probably asking different and more difficult questions.

Then, at the most sophisticated level, we have a group of people who know exactly what they expect, take it for granted, act on it, don’t mind paying for it if necessary and then just get on with the business of whatever it is that they do.

Now, I wouldn’t say that we are all moving towards some end point of workplace sophistication. Nor am I one of those people who claims that we are heading to a period of entropy and the eventual heat death of the workplace. We remain human and until we finally bow the knee to our robot overlords, we’ll still want to be around other people for very humane reasons. Apart from that there are lots of practical reasons why we should continue to work in buildings together. Tom Allen at MIT famously explored how physical proximity affects the way information is shared. Other research has shown how important it is for wellbeing, culture and the sharing of values. Even so, there is no actual reason for us to work in a particular place at a particular time unless we want to or are obliged to.

But the world is changing and there is something amiss with the way many of us think about the workplace. Many of us are like Hiroo Noroda, who sounds like a character from a Douglas Adams book but was in fact the famous Japanese soldier who kept fighting a war that was long over. We need to make sure we are fighting real battles.

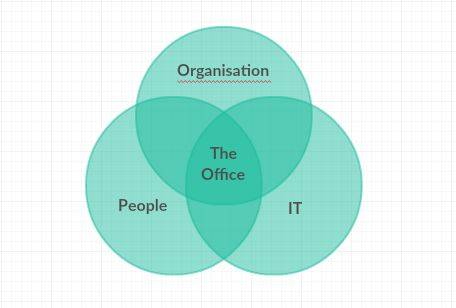

From a professional perspective, we have an enduring conception of how offices function. The traditional view of the office, especially when seen through the lens of facilities management is something like this.

It’s no mistake that FM places itself at the centre of this particular cosmos. No doubt all of the various workplace professions could map out their own place in the grand scheme of things in their own solipsistic way. For FM, We can probably attribute this way of thinking to the great Frank Duffy who, though primarily an architect, could lay claim to be the person who did most to crystallise the conception of modern FM. Duffy and other authors such as Franklin Becker and Erich Teichholz saw the design and management of the physical environment as a means to resolve the tensions that exist between the different facets of the workplace and the different timescales on which they function.

A quarter century or more later, this is still a useful model but its relevance is waning as we move towards a world in which we adopt a more sophisticated approach to where and how we work and with whom. By sophisticated we should acknowledge that this can also mean complexity. It also brings with it some major problems, not least how we adapt as individuals in a world in which space and time no longer behave as they once did.

The implications of this shift are too broad to address in a 20 minute talk and other aspects have been addressed admirably throughout the day, but we can look at three of them in isolation at least.

Media

I’m going to get this one out of the way first because it touches on what I do for a living. The way we think about the workplace is being reshaped by new forms of communication. It used to be the case that people relied on the trade media to keep up to date with ideas and information and it was largely suppliers, contractors, designers and manufacturers who shaped thought through trade magazines, events and other channels, often as part of a commercial tie-up.

Although the better trade titles continue to have a role, their influence is no longer so complete. We know this because whereas we once had to take their word for the number of people who actually read their titles we now know for sure because we can measure traffic online. When we look at these measures, what we find is that there are now a handful of industry websites and journals that retain influence but they now exist alongside clusters of practitioners and influencers who blog, publish and interact on social media. In many cases we know that these people have a larger and more engaged audience than the trade titles that firms give advertising money to.

What surprises me is that firms don’t check on this sort of thing before they spend money on sponsorship and advertising because what they would find is that some websites have pitifully low readerships. They’d often be better thinking how they could engage with the communities of opinion formers that now exist. Or at least listen to them.

This new era of practitioner led opinion-forming and idea-exchange is accelerating the process of sophistication as part of a positive feedback loop. It is also eroding the demarcations between the key workplace professions so that we are seeing a generation of workplace professionals emerging who do not identify themselves necessarily as FM, IT, HR or whatever. How they make their voices heard and how the rest of us heed them will be one of the most important characteristics of the new era.

The Government

I’m not sure the Government really understands the traditional world of work, never mind the one that is developing. This is manifesting itself in a number of ways.

They are more focussed on physical rather than technological infrastructure. I understand the need for capacity in the physical domain but the dead giveaway about their failure to grasp what is unfolding comes in the shape of HS2, a train they are projecting twenty years into the future but with little or no vision or optionality as both Christian Wolmar and Rory Sutherland have highlighted. While most people get hung up on the cost of HS2 its real problem is that it is a rigid and badly integrated piece of infrastructure and it has far fewer benefits than the investment that is still sorely needed in the UK’s broadband and mobile networks. It is an unsophisticated solution in an increasingly sophisticated world. Its original speed-focussed business case relied on the preposterous idea that people don’t work on trains. Even its rethought business case is problematic in the world that is to come because the way we communicate and the way we move ourselves and our things around will be very different very soon.

The government thinks that flexible working is about offering parental rights to a greater number of people in traditional jobs. To be fair, a lot of companies seem to have the same idea.

On a related note the government usually characterises the rise in the numbers of self-employed and freelancers (now approaching a fifth of the workforce) as a triumph of their small business initiatives. Small businesses and freelancers are two different things and even within the freelance sector there are huge differences between people’s experiences and motivations. These people now make up as large a proportion of the workforce as the public sector and yet the government simply does not understand them or know how to introduce policies that will help them. I suspect this will change as we enter the era of automation and calls grow for the introduction of a basic income for all citizens but for now, the voice of freelancers goes largely unheard in Westminster.

The facilities management sector

We’ve heard enough down the years about the nature and role of FM, but the profession or discipline – however you see it – now has the new challenge of what to do with itself in this new era, as do all the other trade bodies routinely issuing their calls to arms. They have tried to branch out but either that has seen them toy with the overlap between FM and HR as we saw with the recent lacklustre partnership between the BIFM and CIPD. Or drift towards their role in cleaning, building management and maintenance as shown in the recent, aborted Building Futures Group initiative.

By the way, there’s nothing wrong with maintenance, as this excellent article in Aeon reminds us. It’s just that if the UK’s FM sector truly wants to develop a major voice in the new era of workplace sophistication it needs to stop nibbling around the edges of technology and people management and park its tanks on the lawns of disciplines like HR, IT, surveying, architecture, property and design.

It’s not just FMs, though. All of us are going to have to adapt to this new world of the workplace even before we learn what exactly the upcoming era of automation means. We must not allow ourselves to be suckered into believing that the world in which we have been successful in the past was built to have us in it. Nor should we panic ourselves into making bad decisions.

We can all get religious about what we do and the teleological argument that suggests that the world was made to fit us has been used for centuries. It explains our place in the world as well as underpinning the beguiling idea that because we so closely fit the world in which we live, we have been put here for a purpose. It’s all for us. The flawed thinking behind this compelling idea was, in my opinion, best illustrated by Douglas Adams and so he will have the final word:

“Imagine a puddle waking up one morning and thinking, ‘This is an interesting world I find myself in — an interesting hole I find myself in — fits me rather neatly, doesn’t it? In fact it fits me staggeringly well, may have been made to have me in it!’ This is such a powerful idea that as the sun rises in the sky and the air heats up and as, gradually, the puddle gets smaller and smaller, it’s still frantically hanging on to the notion that everything’s going to be alright, because this world was meant to have him in it, was built to have him in it; so the moment he disappears catches him rather by surprise. I think this may be something we need to be on the watch out for.”

February 27, 2019

The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Workplace 0

by Mark Eltringham • Comment, Facilities management, Technology, Workplace, Workplace design

The Guide states that the history of every civilisation tends to pass through three distinct phases; those of survival, inquiry and sophistication. The first phase is characterised by the question ‘how can we eat?’, the second by the question ‘why do we eat?’ and the third by the question ‘where shall we have lunch?’

I think the comparison is pretty clear. At the most basic level, owning an office is largely about survival. You need to have an office because you need somewhere to work. It doesn’t really matter that much what it’s like, so long as it doesn’t cost too much and it provides a basic level of comfort and possibly a rudimentary sense of style. This sort of office is far more common than most people care to admit and its role is certainly underplayed in media coverage.

At the enquiry level, people question what they expect from their offices or even why they need an office at all. This question is not as prevalent as it once was, but even the inquiry stage continues, although it’s probably asking different and more difficult questions.

Then, at the most sophisticated level, we have a group of people who know exactly what they expect, take it for granted, act on it, don’t mind paying for it if necessary and then just get on with the business of whatever it is that they do.

Now, I wouldn’t say that we are all moving towards some end point of workplace sophistication. Nor am I one of those people who claims that we are heading to a period of entropy and the eventual heat death of the workplace. We remain human and until we finally bow the knee to our robot overlords, we’ll still want to be around other people for very humane reasons. Apart from that there are lots of practical reasons why we should continue to work in buildings together. Tom Allen at MIT famously explored how physical proximity affects the way information is shared. Other research has shown how important it is for wellbeing, culture and the sharing of values. Even so, there is no actual reason for us to work in a particular place at a particular time unless we want to or are obliged to.

But the world is changing and there is something amiss with the way many of us think about the workplace. Many of us are like Hiroo Noroda, who sounds like a character from a Douglas Adams book but was in fact the famous Japanese soldier who kept fighting a war that was long over. We need to make sure we are fighting real battles.

From a professional perspective, we have an enduring conception of how offices function. The traditional view of the office, especially when seen through the lens of facilities management is something like this.

It’s no mistake that FM places itself at the centre of this particular cosmos. No doubt all of the various workplace professions could map out their own place in the grand scheme of things in their own solipsistic way. For FM, We can probably attribute this way of thinking to the great Frank Duffy who, though primarily an architect, could lay claim to be the person who did most to crystallise the conception of modern FM. Duffy and other authors such as Franklin Becker and Erich Teichholz saw the design and management of the physical environment as a means to resolve the tensions that exist between the different facets of the workplace and the different timescales on which they function.

A quarter century or more later, this is still a useful model but its relevance is waning as we move towards a world in which we adopt a more sophisticated approach to where and how we work and with whom. By sophisticated we should acknowledge that this can also mean complexity. It also brings with it some major problems, not least how we adapt as individuals in a world in which space and time no longer behave as they once did.

The implications of this shift are too broad to address in a 20 minute talk and other aspects have been addressed admirably throughout the day, but we can look at three of them in isolation at least.

Media

I’m going to get this one out of the way first because it touches on what I do for a living. The way we think about the workplace is being reshaped by new forms of communication. It used to be the case that people relied on the trade media to keep up to date with ideas and information and it was largely suppliers, contractors, designers and manufacturers who shaped thought through trade magazines, events and other channels, often as part of a commercial tie-up.

Although the better trade titles continue to have a role, their influence is no longer so complete. We know this because whereas we once had to take their word for the number of people who actually read their titles we now know for sure because we can measure traffic online. When we look at these measures, what we find is that there are now a handful of industry websites and journals that retain influence but they now exist alongside clusters of practitioners and influencers who blog, publish and interact on social media. In many cases we know that these people have a larger and more engaged audience than the trade titles that firms give advertising money to.

What surprises me is that firms don’t check on this sort of thing before they spend money on sponsorship and advertising because what they would find is that some websites have pitifully low readerships. They’d often be better thinking how they could engage with the communities of opinion formers that now exist. Or at least listen to them.

This new era of practitioner led opinion-forming and idea-exchange is accelerating the process of sophistication as part of a positive feedback loop. It is also eroding the demarcations between the key workplace professions so that we are seeing a generation of workplace professionals emerging who do not identify themselves necessarily as FM, IT, HR or whatever. How they make their voices heard and how the rest of us heed them will be one of the most important characteristics of the new era.

The Government

I’m not sure the Government really understands the traditional world of work, never mind the one that is developing. This is manifesting itself in a number of ways.

They are more focussed on physical rather than technological infrastructure. I understand the need for capacity in the physical domain but the dead giveaway about their failure to grasp what is unfolding comes in the shape of HS2, a train they are projecting twenty years into the future but with little or no vision or optionality as both Christian Wolmar and Rory Sutherland have highlighted. While most people get hung up on the cost of HS2 its real problem is that it is a rigid and badly integrated piece of infrastructure and it has far fewer benefits than the investment that is still sorely needed in the UK’s broadband and mobile networks. It is an unsophisticated solution in an increasingly sophisticated world. Its original speed-focussed business case relied on the preposterous idea that people don’t work on trains. Even its rethought business case is problematic in the world that is to come because the way we communicate and the way we move ourselves and our things around will be very different very soon.

The government thinks that flexible working is about offering parental rights to a greater number of people in traditional jobs. To be fair, a lot of companies seem to have the same idea.

On a related note the government usually characterises the rise in the numbers of self-employed and freelancers (now approaching a fifth of the workforce) as a triumph of their small business initiatives. Small businesses and freelancers are two different things and even within the freelance sector there are huge differences between people’s experiences and motivations. These people now make up as large a proportion of the workforce as the public sector and yet the government simply does not understand them or know how to introduce policies that will help them. I suspect this will change as we enter the era of automation and calls grow for the introduction of a basic income for all citizens but for now, the voice of freelancers goes largely unheard in Westminster.

The facilities management sector

We’ve heard enough down the years about the nature and role of FM, but the profession or discipline – however you see it – now has the new challenge of what to do with itself in this new era, as do all the other trade bodies routinely issuing their calls to arms. They have tried to branch out but either that has seen them toy with the overlap between FM and HR as we saw with the recent lacklustre partnership between the BIFM and CIPD. Or drift towards their role in cleaning, building management and maintenance as shown in the recent, aborted Building Futures Group initiative.

By the way, there’s nothing wrong with maintenance, as this excellent article in Aeon reminds us. It’s just that if the UK’s FM sector truly wants to develop a major voice in the new era of workplace sophistication it needs to stop nibbling around the edges of technology and people management and park its tanks on the lawns of disciplines like HR, IT, surveying, architecture, property and design.

It’s not just FMs, though. All of us are going to have to adapt to this new world of the workplace even before we learn what exactly the upcoming era of automation means. We must not allow ourselves to be suckered into believing that the world in which we have been successful in the past was built to have us in it. Nor should we panic ourselves into making bad decisions.

We can all get religious about what we do and the teleological argument that suggests that the world was made to fit us has been used for centuries. It explains our place in the world as well as underpinning the beguiling idea that because we so closely fit the world in which we live, we have been put here for a purpose. It’s all for us. The flawed thinking behind this compelling idea was, in my opinion, best illustrated by Douglas Adams and so he will have the final word:

“Imagine a puddle waking up one morning and thinking, ‘This is an interesting world I find myself in — an interesting hole I find myself in — fits me rather neatly, doesn’t it? In fact it fits me staggeringly well, may have been made to have me in it!’ This is such a powerful idea that as the sun rises in the sky and the air heats up and as, gradually, the puddle gets smaller and smaller, it’s still frantically hanging on to the notion that everything’s going to be alright, because this world was meant to have him in it, was built to have him in it; so the moment he disappears catches him rather by surprise. I think this may be something we need to be on the watch out for.”