In October 1517 Martin Luther nailed his Ninety-Five Theses to a church door in Wittenberg, thereby setting in motion the process that we know now as the Reformation. At least since that time, it has been apparent that a revolutionary manifesto needs to be laid at somebody’s door – or nailed to it – at the right moment for it to achieve its aims. Revolutionary manifestos are easy enough to set out, but the tract is nothing without traction.

In October 1517 Martin Luther nailed his Ninety-Five Theses to a church door in Wittenberg, thereby setting in motion the process that we know now as the Reformation. At least since that time, it has been apparent that a revolutionary manifesto needs to be laid at somebody’s door – or nailed to it – at the right moment for it to achieve its aims. Revolutionary manifestos are easy enough to set out, but the tract is nothing without traction.

Not all have had the immediate impact of Luther’s. The Communist Manifesto of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels remained an obscure pamphlet for a quarter of a century before a treason trial of the three leaders of the German Social Democrat Party in 1872 meant passages were read out in court and hence in a major public arena for one of the first times. This brought it to the attention of a world that was primed for its message and allowed the authors to publish it in large numbers, new languages and new territories, setting in motion four decades of revolutionary thought and action that resonate to this day.

This was an early example of the Streisand Effect, by which an attempt to suppress something merely draws attention to it and so promotes it to a much wider audience.

Just as with major theological reform and political upheaval, so too the parochial world of workplaces. The Marx, Engels and Luther of the workplace in 2018 are – in no particular order – Ian Ellison and James Pinder of 3edges and Neil Usher, the ubiquitous pioneer of a new workplace discipline and one of the lead creators of the outstanding Sky Central facility in West London.

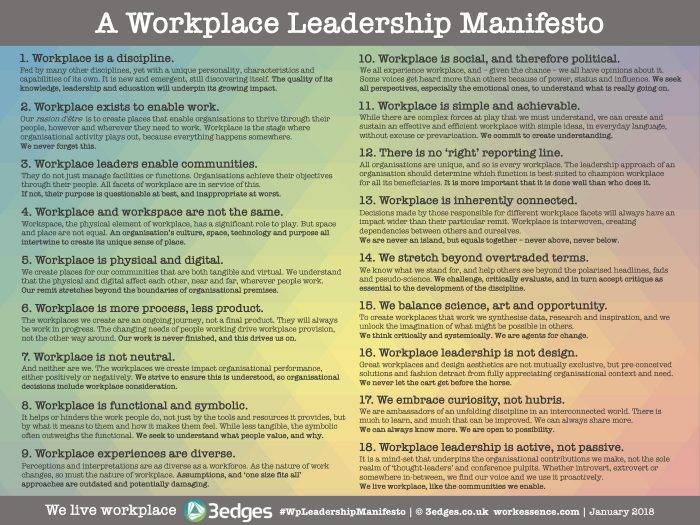

Together they have created a manifesto for workplace leaders, which you can read on Neil’s blog here or download as a poster from the 3edges website (registration required). It’s an ambitious set of ideas. It sets out to define the characteristics of a new workplace discipline that is essentially a chimera spliced from the existing disciplines of technology, HR, facilities management, property and general management. It is the natural end point of an evolutionary process set in motion 25 years ago when mobile devices and the Internet first introduced us to the idea that work was free of time and place. Or could be.

Together they have created a manifesto for workplace leaders, which you can read on Neil’s blog here or download as a poster from the 3edges website (registration required). It’s an ambitious set of ideas. It sets out to define the characteristics of a new workplace discipline that is essentially a chimera spliced from the existing disciplines of technology, HR, facilities management, property and general management. It is the natural end point of an evolutionary process set in motion 25 years ago when mobile devices and the Internet first introduced us to the idea that work was free of time and place. Or could be.

So, the new discipline is a direct consequence of a far broader definition of what we mean by workplace, which is equally cultural, digital and physical. The manifesto is coherent, timely, informed and progressive. It has the potential to define a new workplace singularity.

But will it? To whose doors is it nailed? And how are they reacting to the manifesto and the changes it seeks to crystallise?

Although this is a development that affects people across a range of disciplines and those in the vanguard of the one that is emerging, it is instructive to consider the overall response of the one discipline for which the new era would appear to be a massive opportunity, but which it appears intent on missing.

The problems the facilities management sector needs to face up to

Disclosure. I was the launch editor of a facilities management trade journal published for the first time twenty years ago this month. At the time, FM was something of a nascent discipline. Although it had existed in some form ever since humans first started creating communal buildings, the BIFM had only been formed in 1993 and so there was still a lot of debate in the UK and elsewhere about how to define an inherently diverse discipline and how to promote its message to the wider world.

All of this navel gazing may have been understandable back then, but the fact it’s still happening in the same way two decades later now looks a little adolescent and self-absorbed. Of course, all professions engage in introspection and inquiry and rightly so, but there’s something ill-defined about the way the facilities management sector goes about it right now.

This may be due to the extremely broad nature of what constitutes FM, famously mapped by Martin Pickard here and the underlying principle behind the always dubious claims about the scale of the FM sector.

Yet, speaking as a former insider and now an observer, I feel that there is also an underlying solipsism at play that means the upper echelons of the facilities management sector in the UK cannot see FM for what it is.

For evidence of this we need look no further than the sector’s response to the collapse of Carillion in January. In the three weeks or so since its demise, the familiar refrain in the FM sector has been to suggest ‘well at least everybody’s talking about facilities management now’.

But they’re not. The only people talking about FM in relation to this are people in FM.

If anything, the wider world is talking about sharp accounting practices, poor management, misguided government support and the effect of the collapse on major construction projects and public services.

While it’s true that the failure of Carillion has wider ramifications for the FM sector, that is mainly of interest to the sector itself and primarily the part that constitutes firms like Carillion. The idea that we are now engaged in some sort of national debate about facilities management inadvertently highlights the sector’s self-absorption and professional dysphoria.

While it’s true that the failure of Carillion has wider ramifications for the FM sector, that is mainly of interest to the sector itself and primarily the part that constitutes firms like Carillion. The idea that we are now engaged in some sort of national debate about facilities management inadvertently highlights the sector’s self-absorption and professional dysphoria.

This sheds something of a light on a problem directly related to the workplace manifesto. The FM sector gives the impression that it thinks workplace is a slightly frivolous subset of what it does. This is a potentially fatal fallacy because the opposite is true. Facilities management is an element of the workplace. It is in the belly of the beast, but still thinks it’s the one dining.

What is perhaps more telling is the response of certain individuals who are rooted in the facilities management profession but who have developed or always had a broader focus on the cultural, human and technological facets of the workplace. They’re getting on with the job of opening up new territories, including Neil Usher who was a Head of Facilities when I first knew him but wouldn’t be now.

Although I’m singling out the facilities sector, the changes underlying the manifesto are something we must all look out for. There is an underlying teleological trap we can all fall into; of believing that the world is such a fit for our skills and character that it feels designed for us, rather than that we have adapted our skills and characters to fit the world.

And this is just one half of the existential challenge facing the facilities management sector. The other is manifest in the new business model being developed by the coworking juggernaut WeWork. Last year, the firm announced it was developing facilities management services as part of an integrated business model.

Where it leads others will follow. There are signs that the commercial property sector has woken up to just how transformative the idea of space as a service is, and how the coworking model is attractive to a wide range of organisations, and not just start-ups as they’d originally thought. I’m not so sure the FM sector sees it for the challenge it is.

Unless we all adapt constantly, including to the realities outlined in this new manifesto, we will be swept aside by a reformation. That is a nailed-on certainty.

Image: Julius Hübner’s Der Anschlag von Luthers 95 Thesen, on display at the Lutherhaus in Wittenberg. Public domain

February 12, 2018

Luther, Marx, Engels and a nailed-on manifesto for workplace change

by Mark Eltringham • Comment, Facilities management, Workplace design

Not all have had the immediate impact of Luther’s. The Communist Manifesto of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels remained an obscure pamphlet for a quarter of a century before a treason trial of the three leaders of the German Social Democrat Party in 1872 meant passages were read out in court and hence in a major public arena for one of the first times. This brought it to the attention of a world that was primed for its message and allowed the authors to publish it in large numbers, new languages and new territories, setting in motion four decades of revolutionary thought and action that resonate to this day.

This was an early example of the Streisand Effect, by which an attempt to suppress something merely draws attention to it and so promotes it to a much wider audience.

Just as with major theological reform and political upheaval, so too the parochial world of workplaces. The Marx, Engels and Luther of the workplace in 2018 are – in no particular order – Ian Ellison and James Pinder of 3edges and Neil Usher, the ubiquitous pioneer of a new workplace discipline and one of the lead creators of the outstanding Sky Central facility in West London.

So, the new discipline is a direct consequence of a far broader definition of what we mean by workplace, which is equally cultural, digital and physical. The manifesto is coherent, timely, informed and progressive. It has the potential to define a new workplace singularity.

But will it? To whose doors is it nailed? And how are they reacting to the manifesto and the changes it seeks to crystallise?

Although this is a development that affects people across a range of disciplines and those in the vanguard of the one that is emerging, it is instructive to consider the overall response of the one discipline for which the new era would appear to be a massive opportunity, but which it appears intent on missing.

The problems the facilities management sector needs to face up to

Disclosure. I was the launch editor of a facilities management trade journal published for the first time twenty years ago this month. At the time, FM was something of a nascent discipline. Although it had existed in some form ever since humans first started creating communal buildings, the BIFM had only been formed in 1993 and so there was still a lot of debate in the UK and elsewhere about how to define an inherently diverse discipline and how to promote its message to the wider world.

All of this navel gazing may have been understandable back then, but the fact it’s still happening in the same way two decades later now looks a little adolescent and self-absorbed. Of course, all professions engage in introspection and inquiry and rightly so, but there’s something ill-defined about the way the facilities management sector goes about it right now.

This may be due to the extremely broad nature of what constitutes FM, famously mapped by Martin Pickard here and the underlying principle behind the always dubious claims about the scale of the FM sector.

Yet, speaking as a former insider and now an observer, I feel that there is also an underlying solipsism at play that means the upper echelons of the facilities management sector in the UK cannot see FM for what it is.

For evidence of this we need look no further than the sector’s response to the collapse of Carillion in January. In the three weeks or so since its demise, the familiar refrain in the FM sector has been to suggest ‘well at least everybody’s talking about facilities management now’.

But they’re not. The only people talking about FM in relation to this are people in FM.

If anything, the wider world is talking about sharp accounting practices, poor management, misguided government support and the effect of the collapse on major construction projects and public services.

This sheds something of a light on a problem directly related to the workplace manifesto. The FM sector gives the impression that it thinks workplace is a slightly frivolous subset of what it does. This is a potentially fatal fallacy because the opposite is true. Facilities management is an element of the workplace. It is in the belly of the beast, but still thinks it’s the one dining.

What is perhaps more telling is the response of certain individuals who are rooted in the facilities management profession but who have developed or always had a broader focus on the cultural, human and technological facets of the workplace. They’re getting on with the job of opening up new territories, including Neil Usher who was a Head of Facilities when I first knew him but wouldn’t be now.

Although I’m singling out the facilities sector, the changes underlying the manifesto are something we must all look out for. There is an underlying teleological trap we can all fall into; of believing that the world is such a fit for our skills and character that it feels designed for us, rather than that we have adapted our skills and characters to fit the world.

And this is just one half of the existential challenge facing the facilities management sector. The other is manifest in the new business model being developed by the coworking juggernaut WeWork. Last year, the firm announced it was developing facilities management services as part of an integrated business model.

Where it leads others will follow. There are signs that the commercial property sector has woken up to just how transformative the idea of space as a service is, and how the coworking model is attractive to a wide range of organisations, and not just start-ups as they’d originally thought. I’m not so sure the FM sector sees it for the challenge it is.

Unless we all adapt constantly, including to the realities outlined in this new manifesto, we will be swept aside by a reformation. That is a nailed-on certainty.

Image: Julius Hübner’s Der Anschlag von Luthers 95 Thesen, on display at the Lutherhaus in Wittenberg. Public domain