February 25, 2019

A four day week, people-watching at work, the art of AI and some other stuff

While the recent Finnish pilot of universal basic income had mixed results, a trial of the other most talked about solution to our problem with work – the four day week – has been reported as far more promising. A New Zealand financial services firm called Perpetual Guardian switched its 240 staff from a five-day to a four-day week last November and maintained their pay. The results (registration) included a 20 percent rise in productivity and improved staff wellbeing and engagement.

While the recent Finnish pilot of universal basic income had mixed results, a trial of the other most talked about solution to our problem with work – the four day week – has been reported as far more promising. A New Zealand financial services firm called Perpetual Guardian switched its 240 staff from a five-day to a four-day week last November and maintained their pay. The results (registration) included a 20 percent rise in productivity and improved staff wellbeing and engagement.

Now this might be to some degree the consequence of something known as the Hawthorne Effect, after the famous experiments of the same name. The Effect describes how people not only respond to better working conditions but the experiment itself. The attention it offers them has its own effect; the act of observation changes the nature of that which is observed (with apologies to Werner Heisenberg).

Even allowing for this, the results at Perpetual Guardian also fit with another well-established idea. In this case that there is no fixed correlation between output and the time taken to achieve it. This shows up annually in the disconnect between UK productivity and the many hours more we work on average than people in the countries with substantially higher productivity.

Even allowing for this, the results at Perpetual Guardian also fit with another well-established idea. In this case that there is no fixed correlation between output and the time taken to achieve it. This shows up annually in the disconnect between UK productivity and the many hours more we work on average than people in the countries with substantially higher productivity.

Leaving aside the economist’s definition of productivity, we also know that it is true for individual work outcomes, most famously summed up in Parkinson’s Law, which dates back to the 1950s. Shame that we have to keep relearning it.

Organisations with a culture of long hours also appear to enjoy offering modish perks such as massages, free beer and free dinners, according to this BBC report. Instead, it seems to be far better for them to focus on what the report calls ‘boring wellness alternatives’ which include less time spent staring at a screen, more genuine time off and better physical health. I don’t know why these are described as alternative, because they should be basic.

This debate is distorted by false narratives, many of them peddled by the trade media who should know better. A new piece in the Sunday Morning Herald proves it. It’s a feature full of ideas that are demonstrably true but often obscured by more beguiling, faddish notions.

“You can’t just create a Google-type space and expect that you are going to get innovation, creativity and teamwork,” says Julie Cogin, University of Queensland’s business school dean. “The physical space is important, but what is more important is the culture and other elements of the work environment.”

This statement shouldn’t be noteworthy but the fact that its core idea needs repeating decades after it was first formed tells us something is amiss.

Fit the First

One thing we know that doesn’t necessarily raise productivity but should is technology. The hunt for the Snark of productive tech is evident in this film and report from the OECD, who also describe productivity enhancing tech as The Holy Grail in this piece. I prefer to use Snark as the object of a fruitless quest, because everybody says Grail, the Grail definitely existed and The Holy Grail still makes me think Monty Python. Fetchez la vache!

The potential of tech, or indeed anything, to raise productivity is dependent on what happens when it comes into contact with the ultimate killer variable – people. Which is the animus behind questions such as whether listening to music makes us more intellectually productive (answer: it depends) and whether we write differently on a screen (answer: yes, probably).

People are also prone to be light fingered about certain work related items, especially when they are told that they are free to work from home and elsewhere, according to this piece in The Atlantic.

Creative work and AI

Those of us who nominally work in creative fields might assume we will be some of the last bastions of human endeavour in the wake of the coming robot job apocalypse. Not so, says this book review in The Times (registration / subscription) which suggests:

AI-composed art and literature is proving a harder target than music. Yes, AI can write stock reports and micro-essays, but it struggles with larger-scale form and structure. It can seem aimless. Fine art produced by AI can be disconcertingly derivative. Take the Next Rembrandt produced by a Microsoft-backed Dutch team in 2016, using facial recognition techniques. It looked uncannily like a Rembrandt. But it is hard to read such a project as meaningfully “creative”.

It’s a notion backed by a genuinely disturbing piece on what happens when AI is asked to draw cats. Seth Brundle encountered this problem of tech not getting living things and look what happened there.

Other professions already pondering the impact of automation on their roles include those with bits that can translate without an algorithm being taught the meaning of flesh. This month that includes lawyers and HR managers who already have a certain amount of skin in the game.

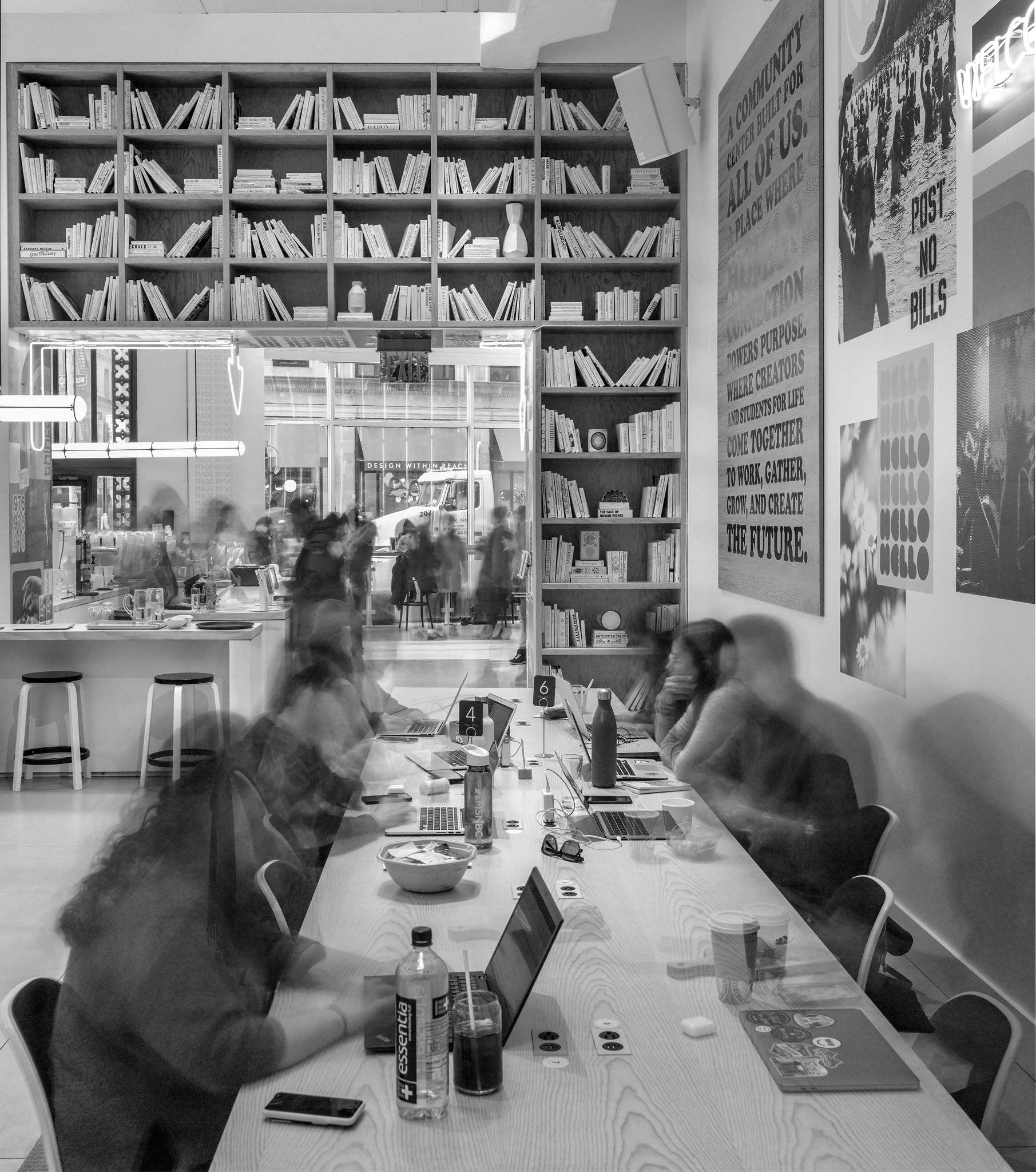

This is WeWork’s world and the rest of us just live in it

The mania about coworking in general and WeWork in particular shows no sign of abating. One of the latest property firms to hitch up is CBRE which has launched its own coworking business Hana and has signed up its first location, according to this report.

The mania about coworking in general and WeWork in particular shows no sign of abating. One of the latest property firms to hitch up is CBRE which has launched its own coworking business Hana and has signed up its first location, according to this report.

The reasons why the property industry is playing catch up in this way is to meet the changing expectations of occupiers, a point explored in this piece from The New York Times Magazine which acknowledges the way that coworking has shifted perceptions of office space generally.

It is also because We Work is moving on to explore new domains. One of them is with the acquisition of a company called Euclid, which is a startup in the office analytics market. The piece seems to be unaware that this is already a mature market and the concerns it raises are very well aired already.

Of course anything that measures behaviour will be subject to this kind of criticism. And inevitably these days this includes the corporate use of fitness trackers. The story offers a perfect example of how a well-intentioned attempt to improve wellbeing and productivity, can arouse suspicions of command and control. We may not work in a panopticon as was once common but the lack of trust is its own concern.

Finally, for everybody who has ever handled an office relocation, spare a thought for the people responsible for relocating the entire Swedish town of Kiruna in northern Sweden which is being moved two miles to avoid being swallowed up by mineworks. As the design team behind the move acknowledge “the challenge for the city is not only about moving an entire city, but also moving the minds of citizens and creating a new home and identity.”

RIP Mark Hollis.

[embedyt] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GFB-d-8_bvY[/embedyt]