October 3, 2019

The art of arranging the world so we do not have to experience it

If you’re a man, each morning as you leave the house you probably perform the bleary-eyed pocket patting ritual that, after a shower, shave and a cup of tea is your sole reassurance that you are in any way prepared for the day ahead. The thinking is that if you’re clean, caffeinated, your flies are up and you’ve got your keys, wallet and phone, you can take pretty much anything the world can throw at you.

If you’re a man, each morning as you leave the house you probably perform the bleary-eyed pocket patting ritual that, after a shower, shave and a cup of tea is your sole reassurance that you are in any way prepared for the day ahead. The thinking is that if you’re clean, caffeinated, your flies are up and you’ve got your keys, wallet and phone, you can take pretty much anything the world can throw at you.

Seems to work more often than not for me and no doubt women have their own version. A little ritual dance, the doorstep twostep. The phone is there in part to listen to a podcast, music or a book on the walk into the office. Terrific, but a very isolating piece of equipment.

[perfectpullquote align=”right” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]A little ritual dance, the doorstep twostep[/perfectpullquote]

This is one of the reasons why people use their earphones at work as a way of both blocking out the racket of the open plan and also indicating to their colleagues that they want to be left alone. On the other hand, I know of at least one design firm that banned their studio staff from wearing them because people had stopped talking to each other.

Yet while there is something unnerving for some about being isolated from their surroundings, that is not true for everybody. You can see on a train how a lot of people seek out isolation. This goes beyond the old practice of putting bags on the seat next to you to discourage people from sitting there and has now taken on a technological aspect. Many of us have become the living, breathing embodiment of the Max Frisch’s observation that technology is the art of arranging the world so that we don’t have to experience it.

This is not a new phenomenon, of course. Back in the heady days of new ways of working hype in the mid 1990s, cocooning was first raised as a potential problem. The idea at that time was that by taking people out of a traditional office setting and ‘empowering’ them to work from home, you would be isolating them not only from work and colleagues but also other people in more general social settings. Except back then, people had fewer and less sophisticated pieces of kit with which to block out the rest of the world.

Isolated thinking

The effects of isolation can be very profound. We’ve always been concerned about the isolating impact of homeworking, for example. Doubtless you’ve heard all the arguments about the pros and cons of remote working so I’ll spare you that here. But I do think that before we give in to people’s apparent wishes and help them to become even more isolated, we are fully aware of the potential impact on their well-being.

[perfectpullquote align=”right” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]Homeworkers can go feral, sitting unwashed in their underwear at lunchtime, discovering Homer-style the additional meal between brunch and lunch and debating when they are actually going to do any work[/perfectpullquote]

This goes a bit deeper than the way homeworkers can go feral, sitting unwashed in their underwear at lunchtime, discovering Homer-style the additional meal between brunch and lunch and debating when they are actually going to do any work. It even goes deeper than the more serious and well researched psychological effects of isolation which can include workaholism, stress, increased cigarette smoking and drinking, weight gain, boredom, dissatisfaction, listlessness and, in extreme cases, mental illness.

Nowhere is the effect of isolation more apparent than when we are driving. Our detachment from our surroundings affects our behaviour in many different ways and makes us do things we wouldn’t dream of doing if we were out in the street. This can range from the oblivious habit of some nosepickers to the experience of road rage, something which affects about 90 per cent of us according to the AA.

There is another theory about driving that says that safety measures and the design of cars in cutting out road noise has helped to make us feel increasingly detached from the rest of the world. Not only does this lead to more road rage, it also gives us an undue sense of our own safety encouraging us to take more risks. The theory is that if you want to make people profoundly aware of exactly what it is they are doing, instead of crumple zones, airbags and seat belts, what they really need is a see-through floor to the car and a ten inch metal spike sticking out from the middle of the steering wheel.

The equivalent, if less drastic, solution for those wishing to maintain an awareness of the outside world when they are working alone is based on technology, our surroundings and good management, both of ourselves and other people. It may lack the immediacy of a drastic reminder of our mortality but it’s just as essential in reminding us that while isolation is a necessity, too much of it is not a good thing.

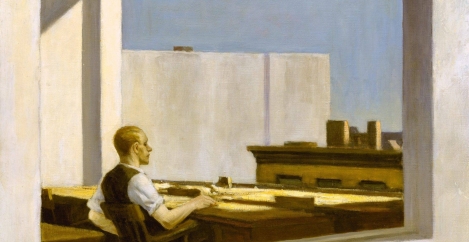

Main image: Office in a Small City by Edward Hopper

The headline is derived from Max Frisch’s description of technology in his 1957 novel Homo Faber as “the knack of so arranging the world that we don’t have to experience it.”

January 21, 2013 @ 5:55 pm

Isolation seems to be an increasing phenomenon in our increasingly connection society. When I work a lot in my home office, I make a concerted effort to get out each day.