December 19, 2019

The truth about all those workplace trends lists

You would not believe the number of firms that ask us to publish a list of workplace trends each week. Or maybe you would, given the number that have appeared elsewhere. Each firm perhaps convinced they are saying something original, unique or interesting, or maybe simply convinced they stand out in some way, while pushing the same timid, stale narratives about the workplace. It goes without saying that the commercialised messages often do little to shine a light on complex realities. In the words of the Scottish poet and anthropologist Andrew Lang, they use information ‘like a drunk uses lamp-posts—for support rather than illumination’.

You would not believe the number of firms that ask us to publish a list of workplace trends each week. Or maybe you would, given the number that have appeared elsewhere. Each firm perhaps convinced they are saying something original, unique or interesting, or maybe simply convinced they stand out in some way, while pushing the same timid, stale narratives about the workplace. It goes without saying that the commercialised messages often do little to shine a light on complex realities. In the words of the Scottish poet and anthropologist Andrew Lang, they use information ‘like a drunk uses lamp-posts—for support rather than illumination’.

That is not to say that they things they say are necessarily untrue per se. Narratives exist precisely because they almost always contain a kernel of truth and so help us understand what is going on. We look for these patterns to make sense of an increasingly complex world.

The author (and undoubted genius) Ray Kurzweil described pattern recognition as the ‘basic algorithm of the neocortex’ in his 2012 book How to Create a Mind. The neocortex is the region of the brain responsible for perception, memory, and critical thinking so his theory is an attempt to get to the foundations of how we perceive things and think about them.

The problem with many of the most commonly accepted narratives about the world around us is that they are low resolution. They lack detail, nuance, layers of complexity and expertise. They are like a child’s drawing of a helicopter. We can all recognise it is a helicopter, but we wouldn’t want to build and fly in one.

Here’s our own list of the most commonly cited workplace trends narratives at the turn of this year and the simplifications and flaws underlying them.

Automation

Hand in hand with artificial intelligence and robotics, the narrative of this next generation of technology is hampered by the problem of visualisation. We have been as guilty of this as many. The truth is that this is largely about infrastructure, much of it invisible. Yet the imagery that surrounds it consists almost exclusively of robots working alongside humans, digitised brains or attractive female cyborgs. That says far more about us than it does the technology.

Hand in hand with artificial intelligence and robotics, the narrative of this next generation of technology is hampered by the problem of visualisation. We have been as guilty of this as many. The truth is that this is largely about infrastructure, much of it invisible. Yet the imagery that surrounds it consists almost exclusively of robots working alongside humans, digitised brains or attractive female cyborgs. That says far more about us than it does the technology.

The issue is also subject to the twin forces of complacency and catastrophisation. A great many people brush the whole issue off, perhaps unaware of the scope and pace of change while many others see it as a threat to human existence. Only the latter have any hope of being proved right. The only possible conclusion is that it’s going to get very complicated, very soon and will do so in ways that affect some people far more than others. The reports may deal in the big numbers and averages, but averages across whole populations will obscure a large number of personal disasters and successes.

Sit-stand

The office design industry loves a panacea and here is a thing that solves two problems at once. Driven by the false narrative that ‘sitting is the new smoking’, the sit-stand desk is actually only able to address the fact that many of us spend far too much time on our backsides staring at screens. But then again, we can address the same issue for free by standing up, going for a walk and looking around. The sit-stand workstation is a good idea but it’s not a silver bullet.

The other problem it solves is rather less talked about. There was a time that the bulk of computer displays meant that workstations were large and L-shaped. All that engineering didn’t come cheap and the industry thrived. The demise of the cathode ray tube and advent tech that worked just as well in Starbucks as anywhere else also created a dip in the revenue of office furniture makers, which they partly filled with a new generation of chairs. From the point of view of office furniture businesses, the sit-stand desk also marks a return to an engineered solution to the provision of a horizontal surface. It is the return of added value to a piece of wood.

Wellbeing and the pathologisation of life

[perfectpullquote align=”right” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]The term ‘medicalisation of dissatisfaction’ describes the process whereby stress becomes the outlet for personal unhappiness[/perfectpullquote]

Winston Smith’s realisation in 1984 that ‘the best books are those that tell you what you know already’ is also true for some ideas. One of my own epiphanic moments came in a conversation about stress many years ago with Stephen Bevan, then at the Work Foundation. He used the term ‘medicalisation of dissatisfaction’ to describe the process whereby stress becomes the outlet for personal unhappiness.

He wasn’t arguing that stress isn’t a problem, just that the issue is complex and determined as much by people’s response to potentially stressful stimuli as by the stimuli themselves. It is also apparent that the more you focus on the issue of stress, the more people claim to be stressed. The act of observation changes the nature of that which is observed.

We not only have a tendency to pathologise elements of our own lives, but are actively encouraged to do so by people who make money when we do. The marketing industry has a long history of this kind of thing, perhaps best exemplified by the story of how an entrepreneur called Edna Murphey employed the copywriter James Young to successfully convince two-thirds of the US women in the early 20th Century that ‘excessive perspiration’ was a serious embarrassment solvable by the use of anti-perspirants.

There is a personal problem here, of course, but the commercialisation of the solution relies on an ability to make it a pathology. We can see the same process at work in a number of facets of the workplace and our working lives.

Vacuous design elements

Dieter Rams once famously said that ‘most people think of design as putting lipstick on a gorilla’. What is perhaps most surprising is that some designers seem to think this way too. The most obvious way this manifests itself in the workplace is in the use of certain design elements in inappropriate settings or as signifiers.

So, there is nothing inherently wrong with using a slide, ping pong table or whatever in an office. Go right ahead and park a VW Camper in the middle of your open plan and claim it’s a meeting room. But if it’s inappropriate, it becomes vacuous and even potentially embarrassing, especially if the rest of the office consists of strip lights, grey chairs, grey desks and blue carpets. It’s a matching comedy tie and socks with an M&S suit. It’s Colin Hunt.

The use of such features may also ignore the fact that specific design elements do not solve any particular issues in themselves and the wider point that culture eats workplace design for breakfast. It’s best to have a place of work that is designed to reflect positive corporate values, but the design of an office cannot overcome a negative working culture.

Millennials

Ho hum. Alongside a number of other people we keep repeating ourselves on this subject, but it never seems to stop the tsunami of bullshit. So. Yet again. Three things.

- Millennials are not aliens.

- The workforce is getting older and more diverse.

- Many of the characteristics ascribed to Millennials are just as easily explained by their stage of life.

Professional navel gazing

So, will this finally be the year that the facilities management profession and its workplace sidecar get their place in the boardroom? No. Is workplace a part part of FM or is it the other way round? Is facilities management even a profession at all? Maybe but who outside of FM cares?

Although it will be the year when we witness the ongoing emergence of a new discipline aligned to an idea of a workplace that is as much technological and cultural as it is physical. This is the core issue facing the whole sector.

The nature of work and workplaces

One of the most disappointing things about the current batch of workplace trends lists is their ignorance of the key issue facing the whole sector, which is the use of space as a service, notably as it manifests in the rise of the coworking sector. Over the past couple of years, the sector has made the crossover to major corporates, thereby defying the idea that it is primarily of interest to impoverished start ups and freelancers unable to afford permanent space in cities. The major players have even extended their offering to include full service packages to attract larger organisations.

This goes hand in hand with a wider trend for people and organisations to move away from long term attachments to physical assets, as chronicled in the new book Capitalism without Capital: The Rise of the Intangible Economy by Jonathan Haskel and Stian Westlake.

The John the Baptist of this era, in the UK at least, is Antony Slumbers who you should really follow on this subject. You can hear him in conversation with Ian Ellison here.

The open plan

As with Millennials, a narrative that simply will not die however often it is argued against or disproved. It is far too simplistic to suggest that the open plan is the physical manifestation of the Taylorist management principles of command and control and that it is responsible for lack of productivity.

As Nigel Oseland and others in the know have demonstrated, there is nothing inherently wrong with open plan offices and – if they are applied correctly – are often the best solution for organisations, especially alongside other forms of space.

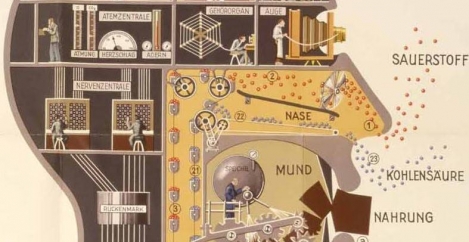

Trends and the future of work

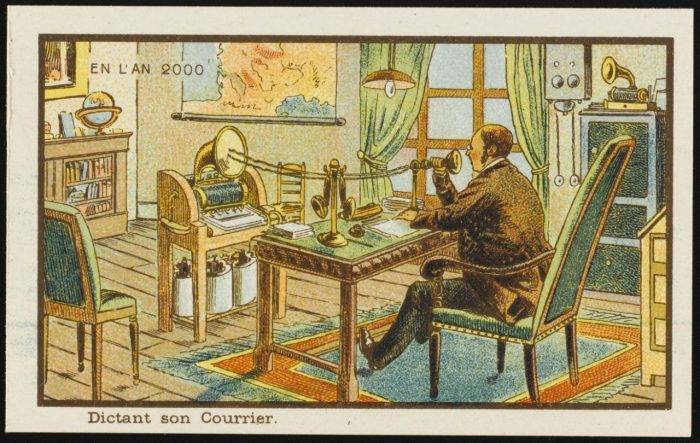

Working life in the year 2000 by 19th Century artist Jean Marc Cote and curated by Isaac Asimov in his book Futuredays.

The problem here is not that trends don’t exist, but the way that ideas that have already become mainstream or have been around for a long time are described as ‘trends’. So, activity based working, flexible working, the gig economy and even coworking all have been around in one form or another for years, decades or even centuries.

If people are going to claim that these ideas are particularly pertinent to the modern world, they need to concede the fact that they are standing on the shoulders of giants.

Then there’s the whole issue of the future of work. Too often this is a reflection of the modern world of work, and the predictions made by authors are nothing more than a realisation of ideas that are already well developed and widely implemented. In the longer term, we really have little idea what the workplace will be like. Only that we will be wrong in any detailed predictions we make about it.