September 22, 2015

The worldwide demographic timebomb is transforming the workplace 0

There are a number of reasons why we shouldn’t be drawn into blindly accepting the narrative about Generation Y’s impact on the workplace. It seems the most important is also the least talked about. It is that the workforce is actually ageing in the world’s leading economies. While it may be true that 27 is middle -aged for employees at technology companies, for pretty much everybody else, shifting demographics, longer lives, improving health, falling pensions and changing personal preferences are likely to mean they stay in the workforce for longer. This is true in both the UK and US, where Millennials may make up the largest demographic grouping in the workplace but are still in a minority within an increasingly diverse workforce. The dynamics of these changes are playing out in different ways in different countries, but the forces are essentially universal.

There are a number of reasons why we shouldn’t be drawn into blindly accepting the narrative about Generation Y’s impact on the workplace. It seems the most important is also the least talked about. It is that the workforce is actually ageing in the world’s leading economies. While it may be true that 27 is middle -aged for employees at technology companies, for pretty much everybody else, shifting demographics, longer lives, improving health, falling pensions and changing personal preferences are likely to mean they stay in the workforce for longer. This is true in both the UK and US, where Millennials may make up the largest demographic grouping in the workplace but are still in a minority within an increasingly diverse workforce. The dynamics of these changes are playing out in different ways in different countries, but the forces are essentially universal.

Japan

In Japan, the lack of younger workers is creating opportunities for older employees to develop new careers, especially women who are increasingly willing to take on shift work and part time and temporary roles, according to this report. It claims that employers are increasingly willing to take on more older workers as they struggle to fill vacancies while employees are taking on work because they want to and because they need work to make ends meet. Often they are jobbers, finding freelance and casual work through websites.

According to the feature, there is a particularly marked increase in the number of older women in the workforce. According to official Japanese Government data, the employment rate for women aged 55 to 59 rose from 58 per cent in 2004 to 66 per cent in 2014. For women aged 60 to 64, the employment rate was 48 per cent, up from 38 per cent in 2004, while it was 31 per cent for those aged 65 to 69, up from 24 per cent 10 years earlier. This trend is likely to continue as the Government seeks ways to address the key challenge acting as a brake on the country’s economic success: Japan today has a less than three people of working age for each retiree in the country. By 2030, it will have less than two.

UK

Meanwhile in the UK things are a little different, although many of the forces at the work are strikingly similar. A recent report from the Scottish Commission on Older Women claims that a generation of older female workers are struggling to balance their need to carry on working with their obligations to family members, especially when they work as carers for their parents or partners. They also face age discrimination and are likely to take on lower paid work than men. The report calls on UK, Scottish and local governments, as well as employers and trade unions, to take steps to improve the situation, including m ore transparency over pay, flexible working policies and statutory entitlement to carers’ leave.

This pattern is replicated across the UK for both older male and female workers and is one of the key drivers of the uptake of flexible working. Earlier this year the CIPD warned that the UK was sleepwalking into a skills crisis because it was ignoring the untapped pool of talent older workers represent, especially women. The challenge for employers is to stop agonising about Gen Y and instead consider how to offer the flexible working and support such workers often need.

Germany

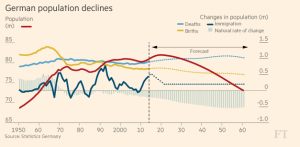

Another European country aware of the ticking demographic time bomb is Germany, as this detailed analysis from the FT uncovers. The solutions mentioned in the article include attempts to increase the birth rate of native Germans and plugging the gaps with immigrants as well as importing talent from Eastern Europe and the US. The crisis facing Germany is particularly severe because the country’s population is now actually decreasing. It peaked at 82 million in 2002, but is set to fall to under 75 million by 2050 with fewer younger people as a proportion of the population than any other country on Earth, while the proportion of over 60s rises from 27 percent to 39 percent over the same period. This will mean a 1.8 million shortfall in the number of skilled workers within 5 years.

Another European country aware of the ticking demographic time bomb is Germany, as this detailed analysis from the FT uncovers. The solutions mentioned in the article include attempts to increase the birth rate of native Germans and plugging the gaps with immigrants as well as importing talent from Eastern Europe and the US. The crisis facing Germany is particularly severe because the country’s population is now actually decreasing. It peaked at 82 million in 2002, but is set to fall to under 75 million by 2050 with fewer younger people as a proportion of the population than any other country on Earth, while the proportion of over 60s rises from 27 percent to 39 percent over the same period. This will mean a 1.8 million shortfall in the number of skilled workers within 5 years.

The underlying problem, according to the feature is that ‘ageing societies are not necessarily good at rethinking’ because older workers have different priorities to younger workers. The example cited is that while the UK is raising retirement ages, and people are working longer voluntarily, Chancellor Angela Merkel has decreased the retirement age for German workers. This may be politically astute but it doesn’t make sense in a country with a population whose average age is already 46, second only to Japan’s. Already one in 20 Germans is over 80. By 2050 it will be one in six, based on UN data.

These trends are apparent worldwide and even include countries like China where the Government is considering reversing its famous policy of restricting families to one child. While such issues are primarily macro-economic, they will also play out in individual workplaces where managers will have to create working cultures and environments that address the needs of an increasingly old and diverse workforce.